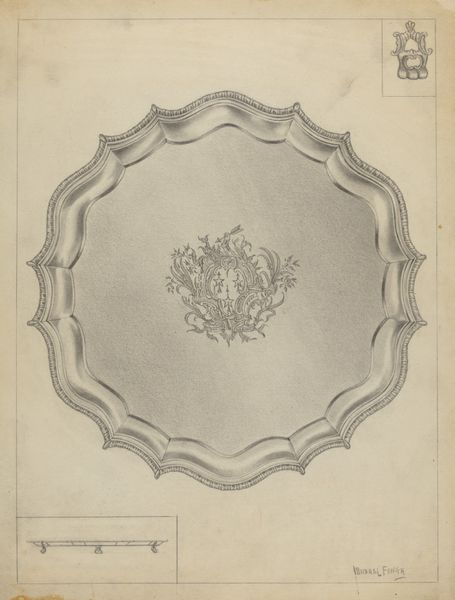

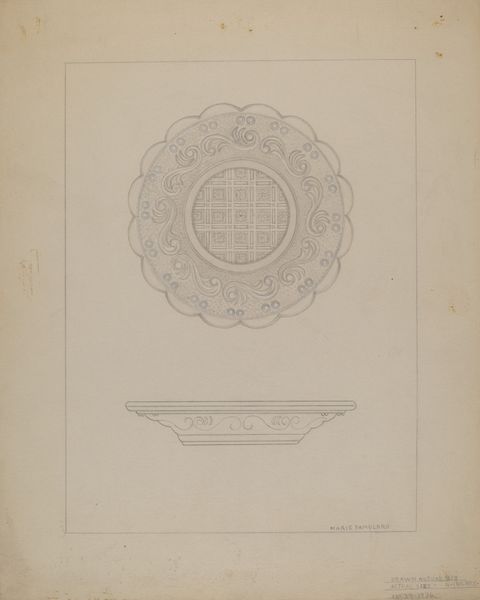

Afbeelding van het Présentoir gebruikt door Z.M. den Koning bij het leggen van den eersten steen op den 17 November 1863 1863

0:00

0:00

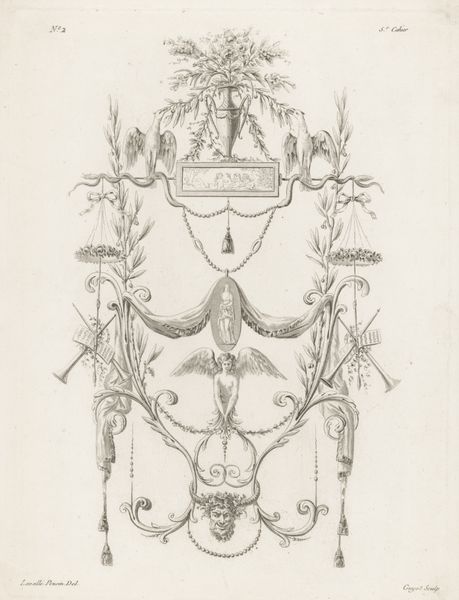

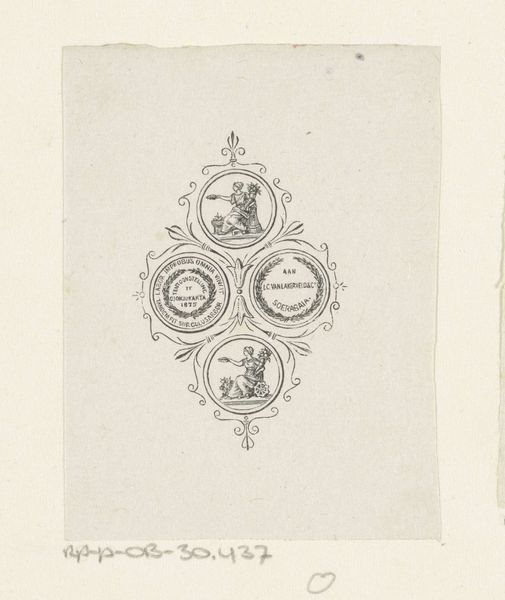

drawing, print, pencil, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

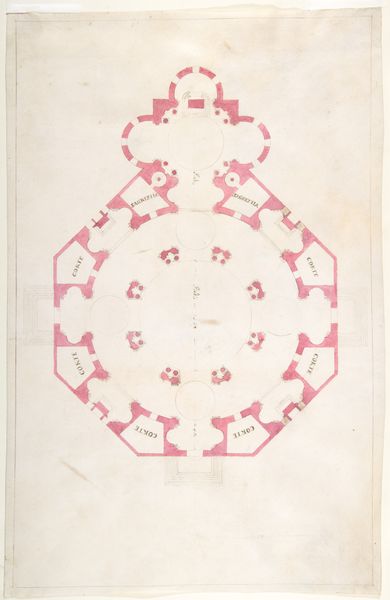

drawing

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 184 mm, width 165 mm, height 479 mm, width 320 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

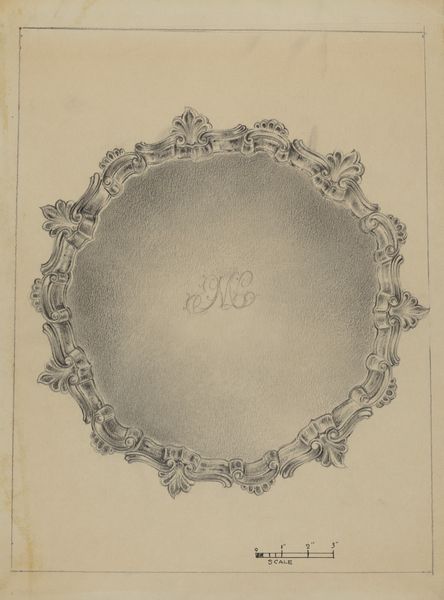

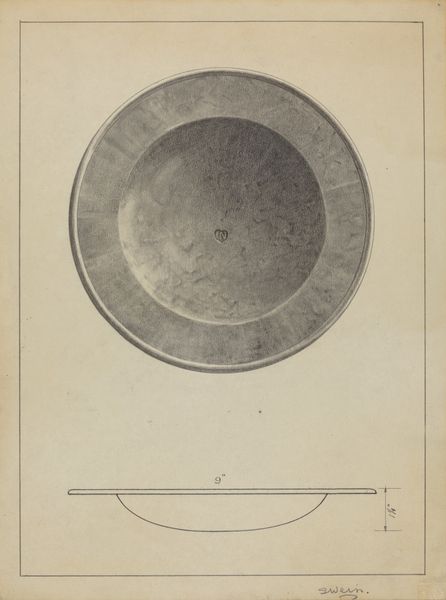

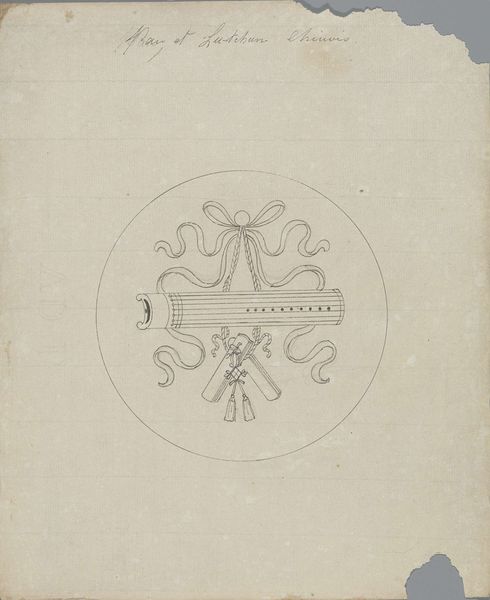

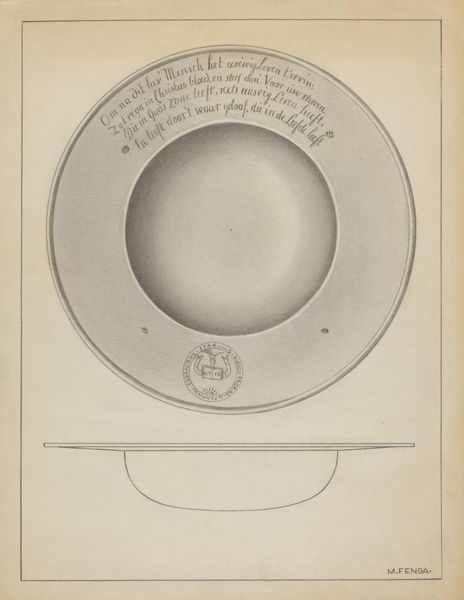

Curator: This intricate print, crafted in 1863 by Willem Matla, is entitled "Afbeelding van het Préseéntoir gebruikt door Z.M. den Koning bij het leggen van den eersten steen op den 17 November 1863", which translates to "Image of the Presentoir Used by His Majesty the King at the Laying of the First Stone on 17 November 1863". Editor: My first thought is, what an artifact! It has a curious formality to it, a historical echo caught in the sepia tones and the fine lines of the print itself. It looks almost like an ornate commemorative plate. Curator: Indeed. Considering the context of its creation, this object speaks volumes about power structures and public display in the 19th century. The piece depicts a specific event: the King laying the foundation stone for some grand public work. This wasn't just about construction; it was a performance. Editor: Absolutely. The monarchy using art and ceremony to reinforce their legitimacy is always fascinating. It makes me wonder, who was this art for? Was it a souvenir for the elite or part of a wider visual strategy to sway public opinion? Did this ritual have ties to prior, religious ceremonies that emphasized patriarchal or colonial dominance? Curator: Good point. These printed images became ways to reproduce and distribute the symbolic weight of such royal occasions to the broader population through affordable art. Matla's skill would have given these objects both artistry and accuracy to serve that goal. Editor: Precisely. We can think of it almost as state propaganda disguised within an aesthetic object, helping maintain public order by carefully shaping perceptions. Even today it brings up complex themes of colonialism, industrial advancement, and hierarchical governance that were essential at the time. The figures in the engraving might well reflect labor relationships—power structures playing out even during public celebrations. Curator: Well, it's certainly more than a simple memento. Looking at the architecture depicted, we can even trace back changing urban environments and patterns. Thanks to Matla, it's more like a lens to reflect back onto shifting cultural perspectives on Dutch history. Editor: Yes, indeed. And by reflecting critically on pieces like this, we open up discussions about contemporary concepts and issues too—like what power *looks* like in the public sphere. Thank you for that illumination!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.