photography

pictorialism

landscape

abstract

photography

monochrome photography

modernism

monochrome

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to image): 11.9 x 9.3 cm (4 11/16 x 3 11/16 in.) mount: 34.8 x 27.4 cm (13 11/16 x 10 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

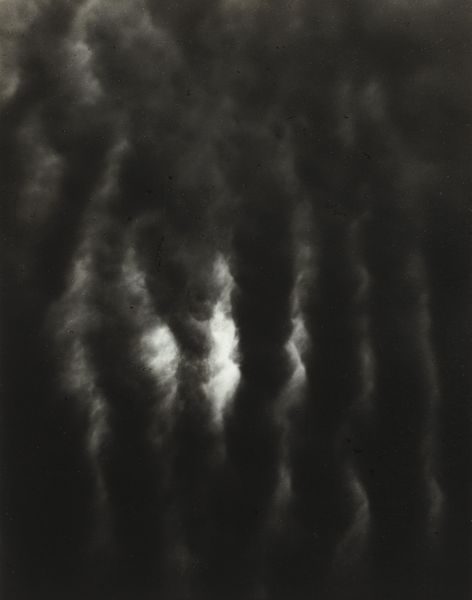

Curator: Wow, this photograph pulls me right in! It feels so expansive, almost cosmic. Editor: We're looking at Alfred Stieglitz's "Equivalent, Set C2 No. 2" from 1929, a black and white photograph. He really pushed photography into the realm of modernism. Curator: Modernism? I see these gorgeous swirling clouds. There’s such raw emotion – like nature reflecting my inner self back at me. Editor: That's exactly what Stieglitz intended! He called these his "equivalents," these photographs weren't meant to represent actual clouds. They were about capturing the feeling, the essence, of an emotion, or a state of being. The goal wasn't a literal transcription but, instead, emotional correspondence, particularly pertinent at a time of rising anxieties on race and class divisions during the Harlem Renaissance. Curator: So, these clouds aren’t really clouds? He’s using them like metaphors…for what? The complexities of being alive? Editor: Precisely. He strips away context and location to encourage introspection. Consider how landscape, historically a celebrated art form dominated by white artists, intersects with the politics of visibility and representation in early 20th-century America. Whose experiences get centered in these universal emotional landscapes? Who is afforded this privilege? Curator: That makes me rethink the small disc in the centre – is that the moon? It felt serene earlier, but now there's an intensity – it could just as easily be an eye, scrutinizing or judging! Editor: The image can feel both comforting and unnerving, can't it? And the use of monochrome only intensifies that sense. The absence of color encourages us to consider the stark contrasts inherent in lived experiences, the dualities of light and shadow, presence and absence, which often mirror power dynamics within society. Curator: It's a brave way to use a camera. You know, to point it upwards, to inner space! And perhaps not even space… but feeling. It really unlocks something… Editor: Stieglitz was aiming for transcendence, albeit tinged with the realities of the era. His photographs challenge us to confront uncomfortable truths about ourselves and the society we inhabit. Curator: Well, now, thanks to your insight, this evocative work isn't only aesthetically captivating. I understand now it is meant to urge its viewer to connect with that experience with the world and its complicated times in their core, even, by thinking about feelings, even at their extremes. Editor: Indeed! Thinking critically can deepen the encounter of art and self.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.