photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 82 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

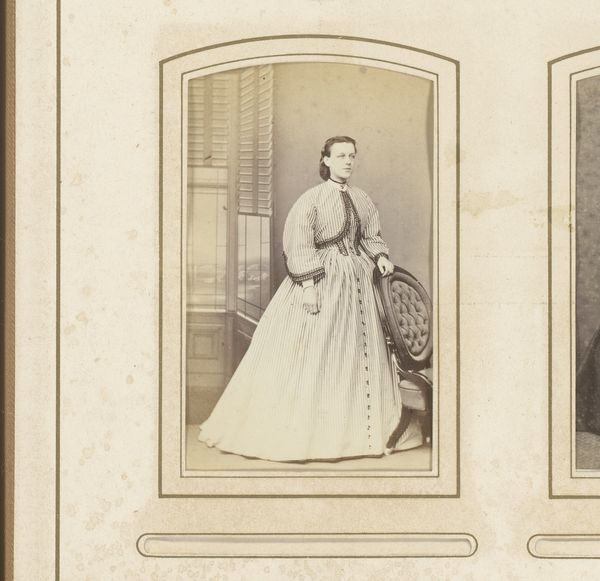

Curator: This is "Portrait of a Young Woman Standing by a Chair," an albumen print dating from roughly 1857 to 1908 by Woodbury & Page, housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. There’s something quite captivating in its simplicity, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Absolutely. The sitter's direct gaze projects such quiet confidence despite the stiffness often associated with early photography. Her dress, though—the volume of fabric is the first thing that grabs my attention. The material looks incredibly heavy. Curator: And what a production it must have been! From textile manufacture, perhaps involving exploitative labor practices across global trade networks, to the sheer construction of the garment. Every fold and drape required skill and resources. Editor: Definitely. And beyond the implied labor in creating that dress, there is labor of display: it’s almost a visual representation of restrictive gender roles. She’s literally burdened by the fabric, positioned passively, her status signaled by this cumbersome garment that inhibits movement. Curator: Right, and think about the process of taking this photograph. Wet collodion was likely used, demanding precise chemical knowledge and rapid execution. Every step from preparing the glass plate to printing demanded skillful handling. The final product, the print, becomes a record of all this labour. Editor: It is. But the very act of portraiture at that time had social implications as well. Owning this photograph meant participating in a growing culture of representation, visibility and self-fashioning, reflecting a shift in power dynamics but still filtered through a lens of societal expectations for women. Curator: Precisely. And consider Woodbury & Page themselves. As studio photographers working in what was then the Dutch East Indies, their practice intersects with colonial narratives of image-making. This object reveals those relationships as much as it obscures them. Editor: So, it isn’t just an innocent snapshot. It captures not just the image of a woman but a nexus of social, economic and colonial factors made material through photography. Curator: It reminds us that every image is built from many materials and choices—nothing is neutral. Editor: And, by unpacking them, we understand how much this young woman’s experience would have been a result of specific political structures of the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.