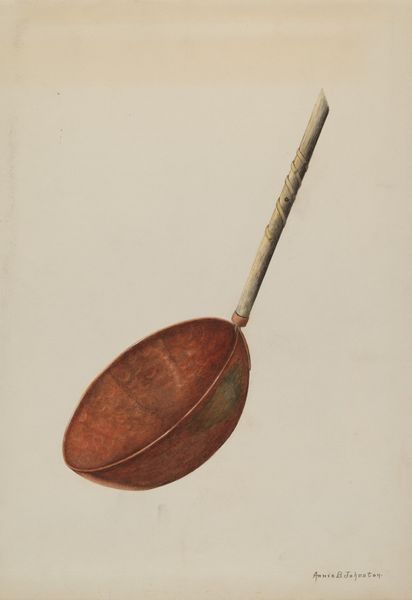

drawing, watercolor

#

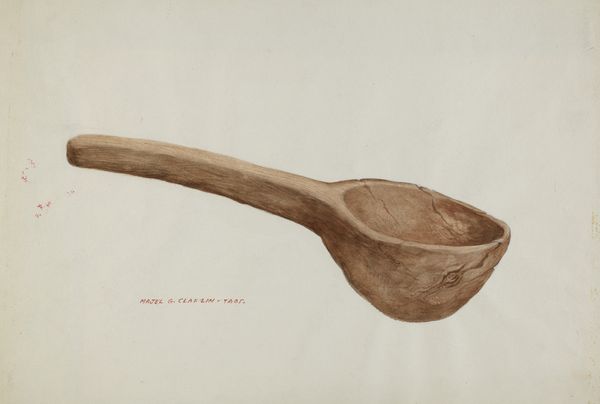

drawing

#

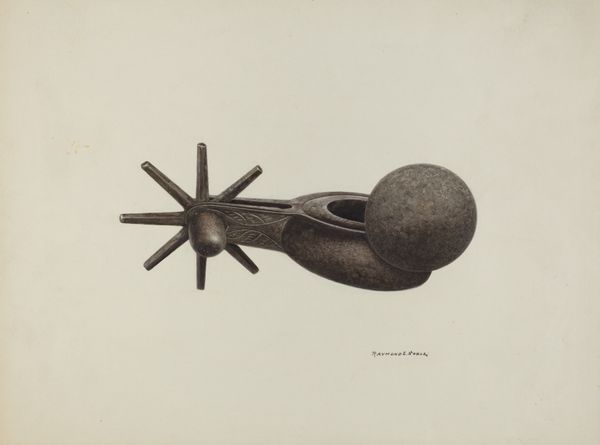

charcoal drawing

#

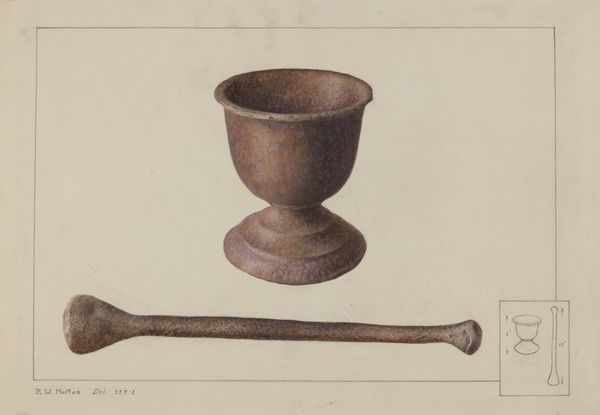

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: overall: 24.7 x 35.8 cm (9 3/4 x 14 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This watercolor and drawing, titled "Saddler's Mallet," was completed by Alexander Anderson in 1940. The object is placed deliberately on a neutral surface. Editor: There's a striking simplicity. The realism makes the object loom almost heroically, despite being a rather humble tool. Curator: Indeed. Consider the context. Anderson, like many artists during the Depression era, focused on the dignity of labor and craftsmanship. This mallet wasn't merely an object, but a symbol of skilled work, specifically saddlery—an important trade. Editor: So, its meaning is tied directly to the working class and their tools. I see this not as an act of merely presenting realism but giving importance to the workers. Did the cultural institutions of the time embrace art focusing on ordinary tools? Curator: Not always immediately. The art world was still heavily invested in traditional subjects, although modernism was slowly gaining ground. Art during this time served different ideological roles that still have the same social issues today. The choice of watercolor is itself significant, a traditionally 'lesser' medium applied to a 'lesser' subject. Editor: And it brings a certain accessibility to the viewer. The grain of the wood on the head and the worn handle really speak to the hand that held it. There's no embellishment, it is very straightforward, honest. Were such images ever intended to promote any social ideology? Curator: Likely so. Realism, at this time, was tied to ideals of national identity and valuing 'true' labor against a backdrop of rapid industrialization. It could reinforce pride in a nation's workforce while speaking for social responsibility, and a dignity we often now ignore in contemporary mass consumerism. Editor: Looking at the way Anderson chose such ordinary subject, and seeing with great dignity is inspiring. It almost gives new eyes to objects that are cast aside after mass-production has overshadowed what makes labor special and dignified. Curator: Precisely. Anderson forces us to acknowledge that the tool in itself, divorced from the act of labor, embodies stories of work, of hands, and indeed, social and cultural history. Editor: A perspective that shifts how we understand our own place in that chain. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.