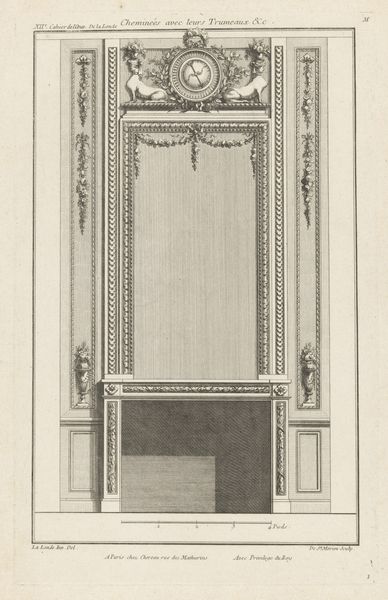

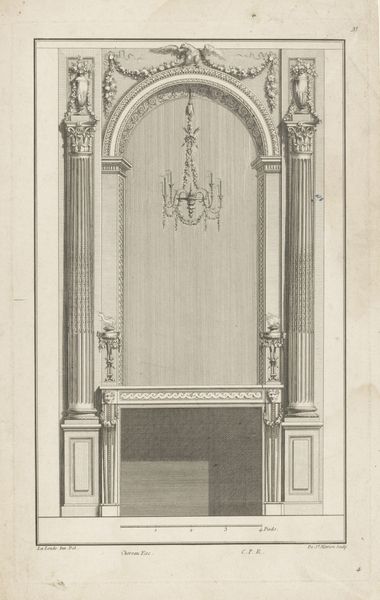

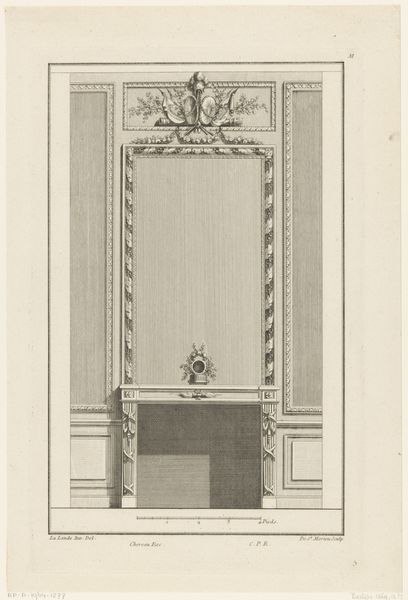

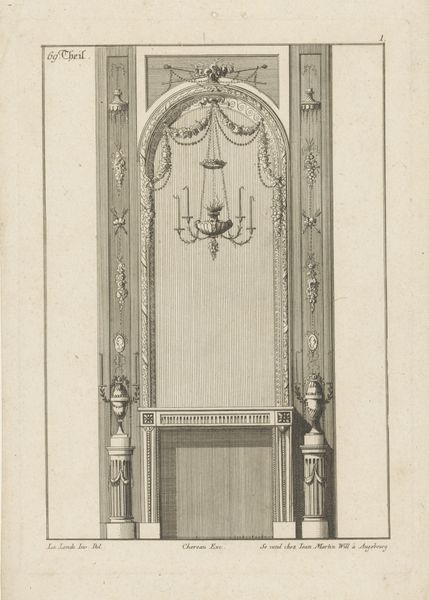

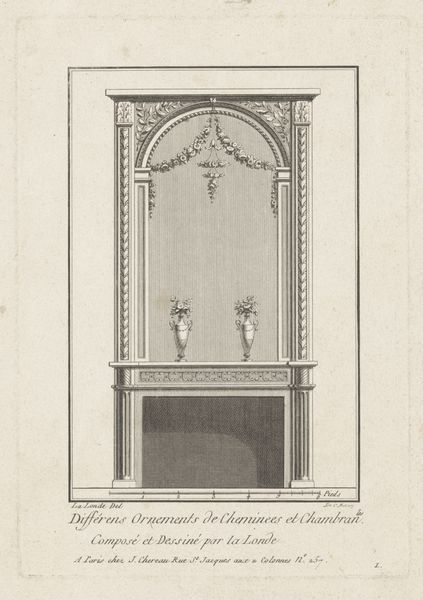

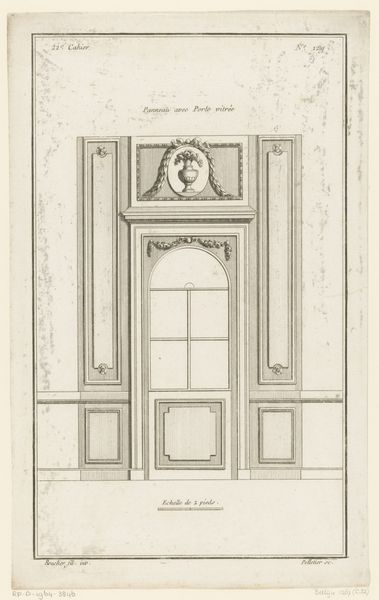

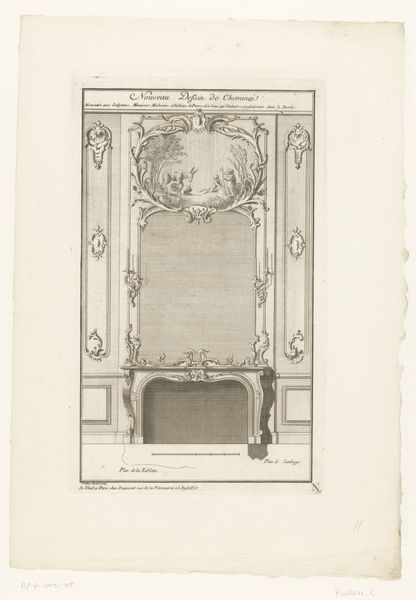

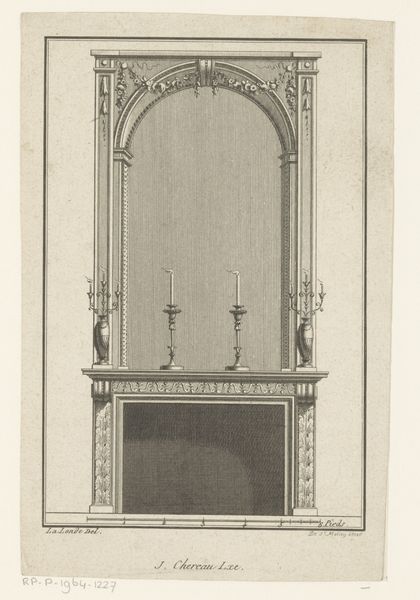

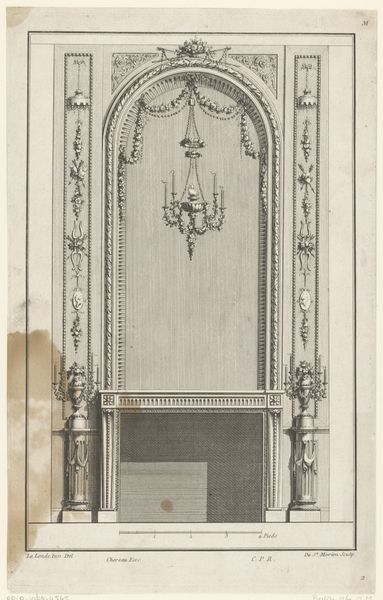

drawing, print, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

#

historical design

#

neoclacissism

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

light coloured

#

historical photography

#

geometric

#

19th century

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

#

architecture

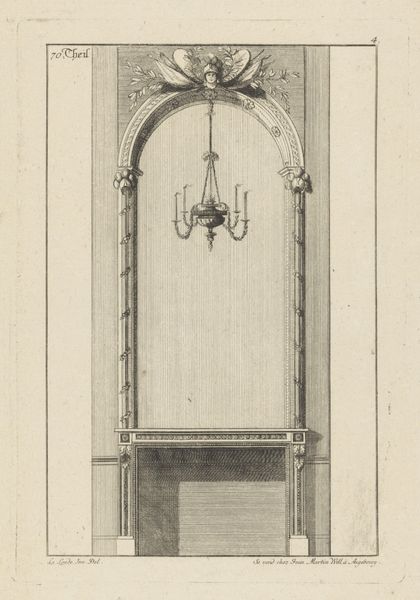

Dimensions: height 345 mm, width 218 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is an engraving titled "Schouw met kroonluchter," or "Fireplace with Chandelier," created around 1784-1785 by de Saint-Morien. Editor: The drawing feels so austere, doesn’t it? Like a stage set stripped bare. The geometric fireplace looming below the fragile chandelier – there's almost a threatening stillness to the image. Curator: As a product of its time, the drawing offers clues about material conditions in the late 18th century. We are seeing neoclassicism leaning into severe geometry and rationalized production, evidenced here by its precise rendering for print reproduction. Editor: Precisely. The severity, as you say, also evokes classical ideals—order, reason, civic virtue, and of course, status. Think of the laurel wreaths and classical heads adorning the columns, almost demanding a sense of decorum. What meaning would such iconography hold for its intended audience? Curator: Possibly instructions to craftsman replicating fireplace. Notice the level of ornate design detail, indicating a degree of specialized labor. The etching gives us insight into consumption practices where aspirational objects needed to be designed, built and integrated into someone's home, possibly far away. Editor: I see the interplay of symbolic meaning and function as almost paradoxical here, no? The chandelier itself, hanging like an emblem of affluence, casts no real light in the image – a symbol divorced from utility. It suggests a concern for appearance over practical use. Curator: Very astute. If we broaden our focus to look at social history of production, we may find clues about divisions of labor in this image, too, and a desire for mass production over individuality. A loss. Editor: Perhaps. Either way, this glimpse of Neoclassical interior design really prompts thinking about luxury and its visual language. Curator: Agreed, luxury wasn’t for the people but a means of visual and material differentiation. It reflects societal divisions which drove production further and further into industrialization. Editor: This discussion certainly changed my view of what I initially perceived to be stark illustration! The conversation gave some intriguing entry points on symbolic function in domestic life during the period, and of industrialism to come.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.