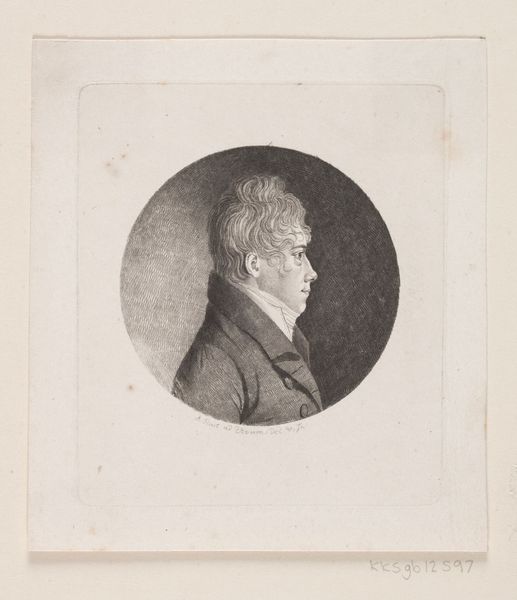

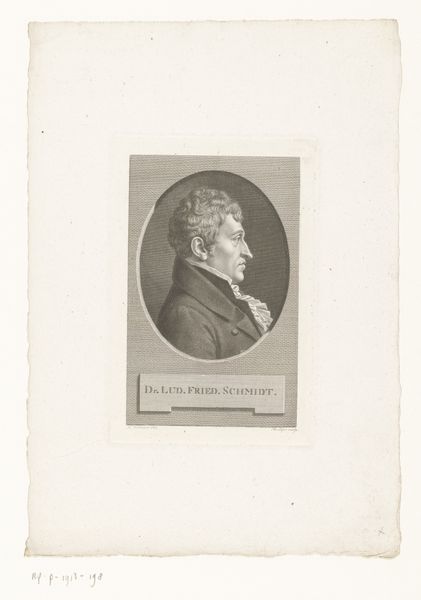

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

form

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

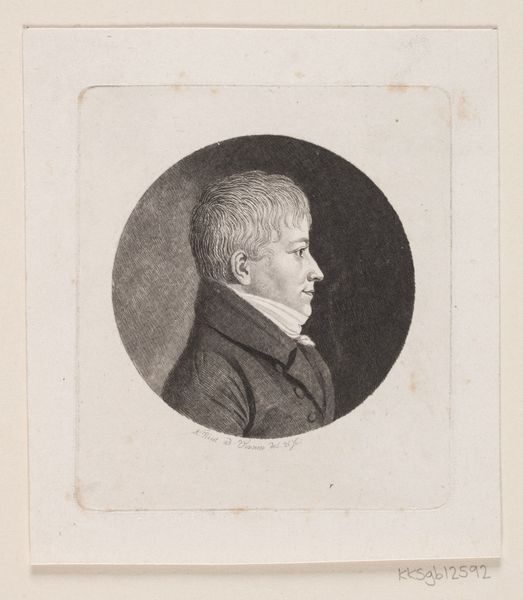

Dimensions: height 68 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, made sometime between 1846 and 1852, presents a portrait of Pieter Gerardus Duker, captured by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin. The artwork is an engraving. Editor: It’s remarkably stoic, isn’t it? A profile view encased in that stark circular frame gives it such a detached, almost clinical feel. It also lends him the visual power reminiscent of classical Roman emperors' portraits, though perhaps it's meant ironically. Curator: It’s definitely rooted in Neoclassicism, which sought to revive the aesthetics of classical antiquity. Think about how these images worked as social currency: who was memorialized, and what visual language was employed to signal their status? That high collar and tightly curled wig would have definitely been intentional. Editor: Of course, style wasn't just an aesthetic choice, but a very powerful message within the social structure of the period. Do you think the black and white is integral to the statement or an unfortunate accident stemming from limitations of the engraving method? Curator: The starkness adds to the effect, amplifying the clarity of line, which for me, becomes very telling. The engraver isn’t simply documenting a likeness; he is codifying Duker as a type of ideal – the intellectual, the patrician… He becomes an archetype more than an individual. The way the light catches his brow makes it a clear symbol. Editor: Interesting. The line-based style reminds us that power isn't created randomly, it requires planning and execution—much like creating such a controlled and stylized depiction, for what looks like a clear piece of propaganda. I do like its restraint. There's an argument to be made about how sometimes "less is more", the composition amplifies this artwork's meaning. Curator: Indeed, this type of print was meant to circulate, shaping perceptions and bolstering reputations through careful management of image. It would definitely have had that role, if we understand propaganda as the calculated dissemination of images for an elite’s benefit. Editor: It really showcases the intersection of art and socio-political machinations doesn't it? It goes far beyond aesthetics. I guess it all comes back to that potent idea: images carry a significant weight. Curator: And that weight is still being felt and processed in today's cultural memory. I mean, we are standing in front of the piece today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.