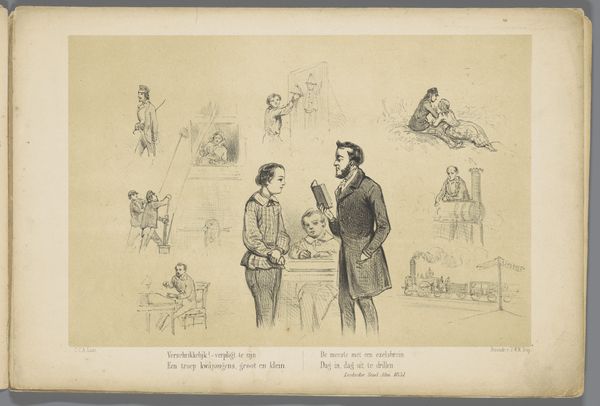

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

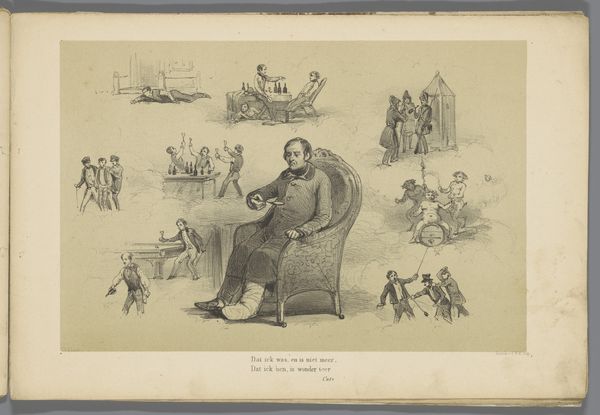

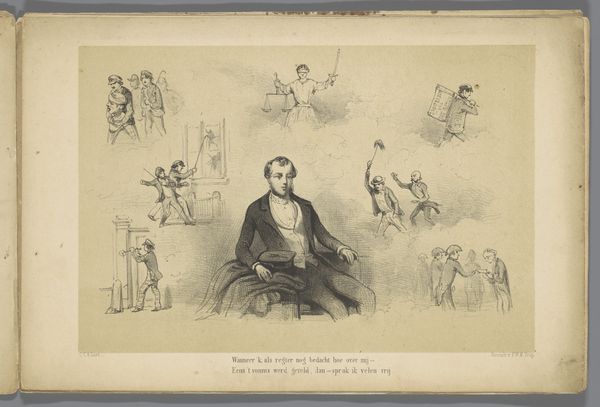

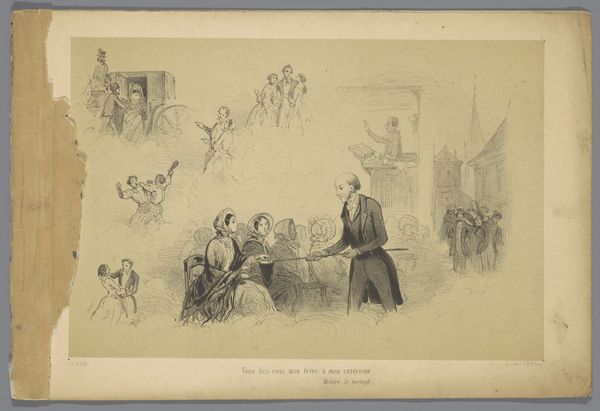

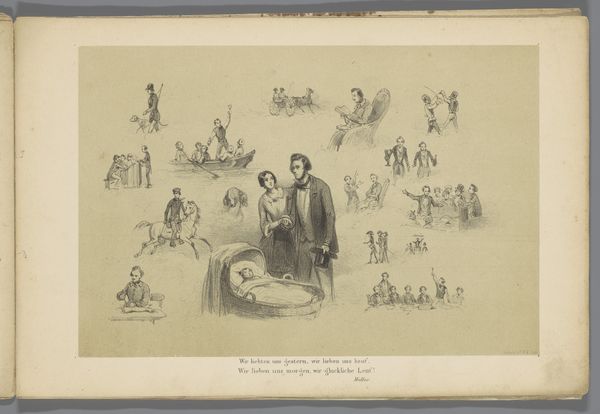

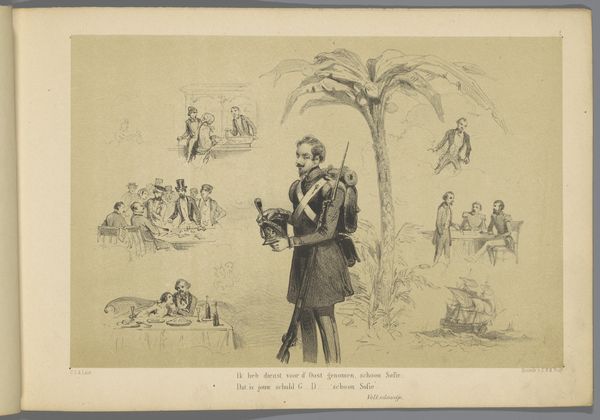

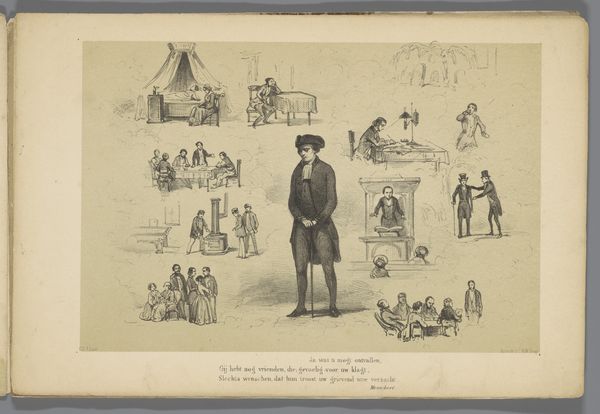

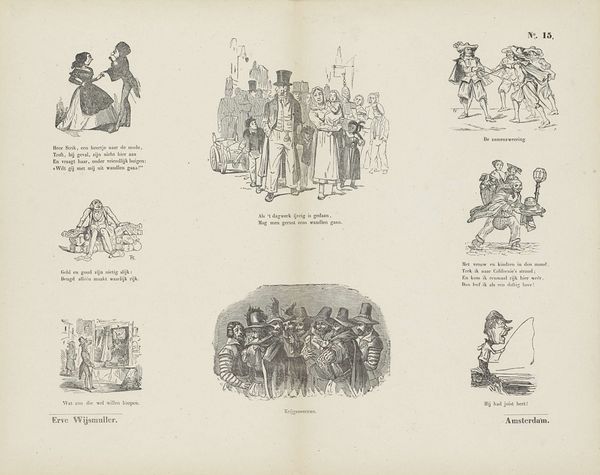

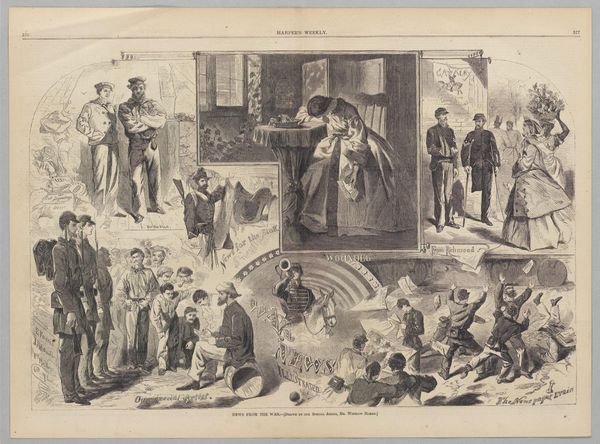

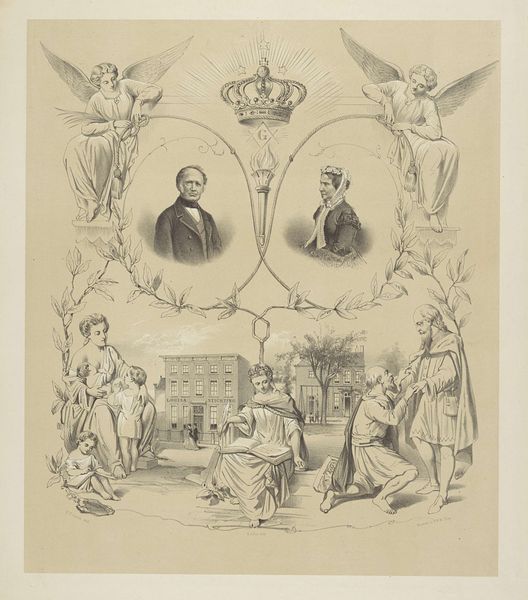

Curator: This piece, currently residing at the Rijksmuseum, is called "Man in kamerjas omringd door taferelen," dating roughly between 1836 and 1876. It is attributed to Carel Christiaan Antony Last. Editor: It looks like a lithograph—delicate lines rendered in ink on paper. The central figure is a man in a dressing gown, surrounded by these ephemeral vignettes. Almost like glimpses into his life or perhaps just fantasy. There's a dreamlike quality, due to the rendering in line alone. Curator: That airiness makes sense. Last often played with the symbolism of dress and implied status, but here he positions the man—presumably bourgeois based on the robe—within a web of daily narratives. The surrounding vignettes include family scenes, perhaps moments of leisure, of celebration, or even instances of sorrow, framed as they are almost like windows to memory. The robe, almost a protective garment against the outside. Editor: Interesting you note the robe as protective! It's clearly well-worn. If you look closely, the details of its rendering reveal its materiality: where it creases, how it folds around the man’s frame. One begins to consider where the fabric was made, the economics of clothing for bourgeois men. And look! Each of these tableaus, in their own way, implicates production— look closely at these tiny scenes depicting labor, celebration, family relations. Curator: Exactly. The man is literally wrapped up in the tapestry of his world, both actively creating it, being supported by its production, and feeling beholden to participate and partake. Each scene contributes to a vision of belonging to an emerging world, a middle-class Dutch sociality. This imagery taps into familiar emotional reservoirs— love, grief, celebration. It reinforces an accepted story. Editor: Do you find these kinds of graphic reproductions circulated widely? Because that changes how the material of "art" is then consumed in daily life. Curator: Most definitely. Inexpensive reproductions like this brought art, or rather imagery, to a much wider public and encouraged a shared emotional language and sense of values through the daily use and familiarisation of those circulating pictures. It's not about individual ownership, or uniqueness. It's a tool to visualize your everyday position in the world. Editor: So this piece invites us to think not just about *what* is depicted but how the materiality, print-making, and its easy accessibility participated in solidifying class consciousness in nineteenth-century Holland. Curator: A material record that helps make our culture comprehensible through easily understood pictures. Editor: A mass cultural product with surprisingly individual resonance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.