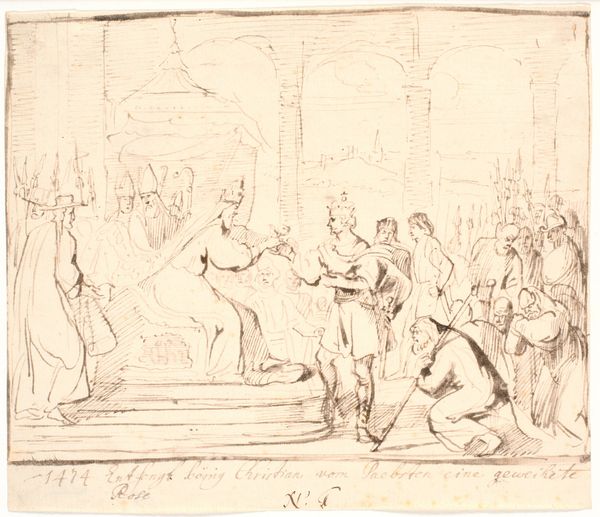

drawing, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

mannerism

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

group-portraits

#

pen

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 262 mm, width 420 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find myself drawn into this drawing. Titled "Veldheer in een vergadering voor zijn vorst tredend," which roughly translates to "A Commander Appearing Before His Prince in Assembly", it’s attributed to Bernardino India and dates roughly between 1538 and 1590. The medium here seems to be pen and ink. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: My first impression? Haste. It feels sketched rather than planned. Look at the figures on the left – the lines are so quick they barely have form. I wonder about the paper; it doesn’t seem highly processed given the period. Curator: Indeed. It is interesting how the artist used ink to capture what appears to be a significant moment, a presentation perhaps? We see symbolic objects—the fasces, suggesting power and authority—almost as much of a focus as the human figures themselves. Do you notice how the eye is directed towards the seated figure who is probably the prince? Editor: Right, but even *that* figure, arguably the central subject, is depicted with minimal detail! The hasty sketch lends itself to wondering where this sketch was meant to go - what was its purpose, who was it intended for? The material application here feels distinctly preparatory. Curator: I agree. Given the timeframe, around the mid-to-late 16th century, we might place this work within the Mannerist style. It's known for elongated forms and somewhat stylized presentation which definitely applies to some of the subjects here. Observe the repeated postures and the theatrical arrangement. Editor: The production of drawings like these reveal much. Paper production at the time involved significant labor; linen rags were broken down, processed, and then formed into sheets. We think of drawings being quick gestures, but they relied on intricate, involved material economies. Curator: That is true. So, returning to symbolism, think about how power dynamics are communicated. The very act of kneeling and the raised hand could be indicators of supplication and request for endorsement. I see it as very illustrative of leadership ideals and norms of its period. Editor: Exactly! What we consume as this seemingly weightless, spontaneous act, this 'drawing', has these fascinating material roots. By focusing on that labor, we get insight on this era's entire economic machine. I suppose what India captured might be linked to how it was made. Curator: Absolutely! When looking at artworks, it is rewarding to discover hidden elements that echo deep seeded meaning and values that transcends surface aesthetics. Editor: Yes, sometimes the story isn't just *in* the image but also behind its very making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.