drawing

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

romanticism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

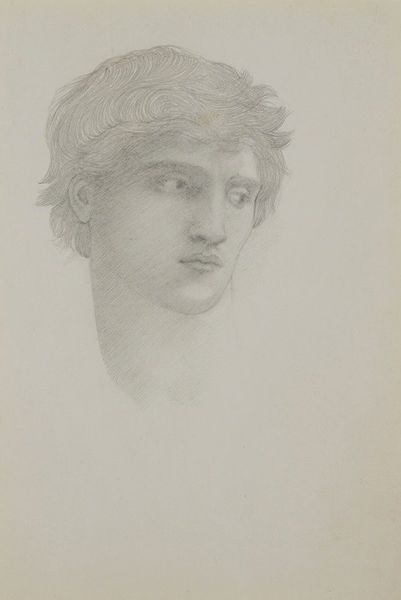

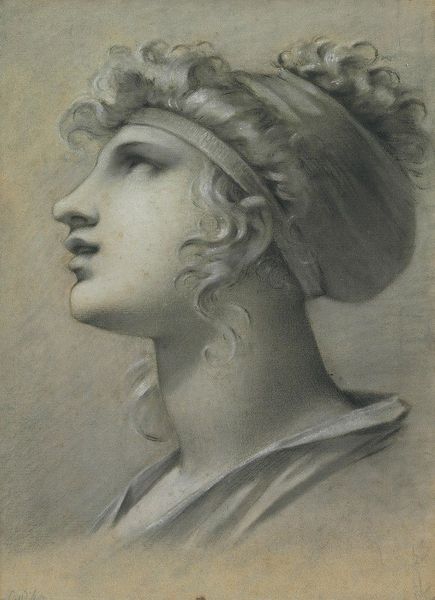

Editor: Here we have "Tête de Femme" by Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, created around 1800. It’s a drawing, and the tones feel so soft, almost dreamlike. What strikes me most is the expressiveness Prud'hon achieved with, seemingly, such simple materials. What's your perspective on this piece? Curator: I am intrigued by the seeming simplicity you note. Consider the societal context: Prud'hon was working during a period of great upheaval. The shift from aristocracy towards burgeoning industrialization demanded new visual languages. Here, charcoal and chalk, inexpensive and readily available, replace the oils typically patronized by the elite. Is this shift in medium simply a pragmatic decision, or a quiet revolt? Editor: A quiet revolt, that's fascinating! So, you're suggesting the choice of drawing over painting, of charcoal over oils, is significant because it democratizes art-making, making it less reliant on expensive materials only the wealthy could afford? Curator: Precisely. Look closely. Prud'hon achieves luminosity with humble materials, demanding skilled labor rather than lavish spending defines artistry. He elevates a ‘lower’ medium to the status of high art, challenging established hierarchies. How does understanding this impact your initial impression of "softness"? Editor: It makes me rethink that initial impression. The softness is still there, but now I see a kind of subtle defiance woven into the very fabric of the drawing, achieved with simple means and lots of hard work, turning something almost austere into something beautiful. Curator: And doesn’t that tension encapsulate the revolutionary spirit? It uses accessible means to communicate something enduringly powerful. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking about the materiality and context has completely transformed my reading of this artwork. It's no longer just a beautiful drawing, but a statement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.