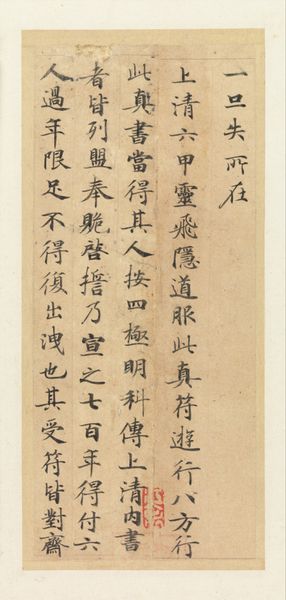

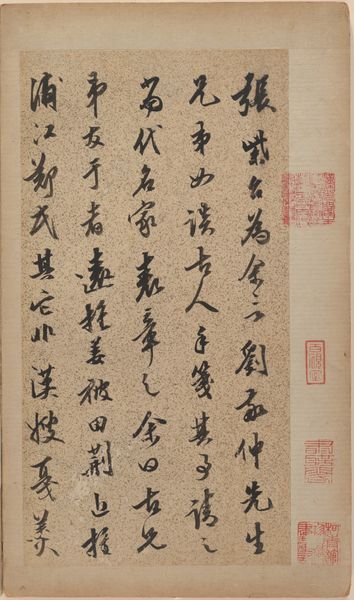

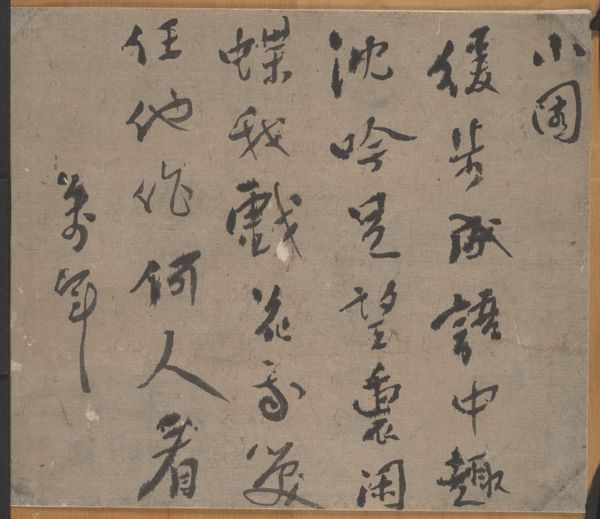

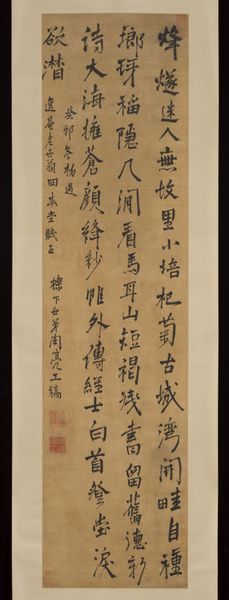

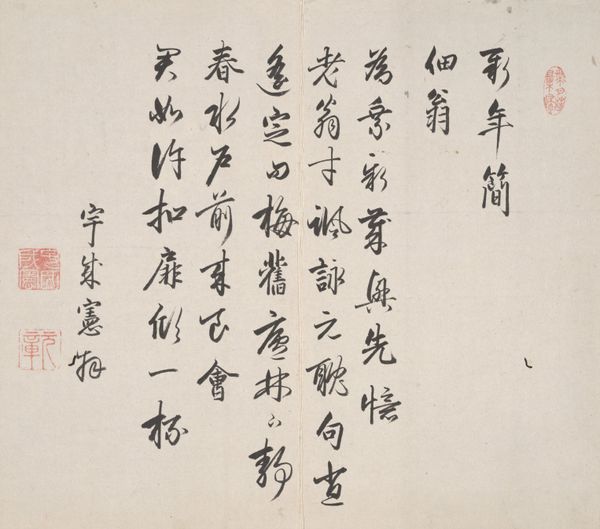

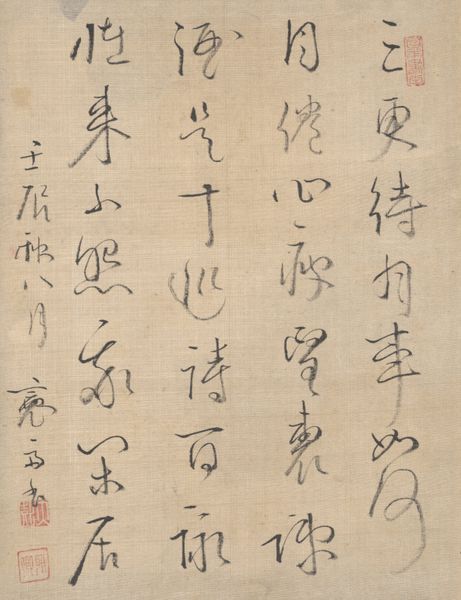

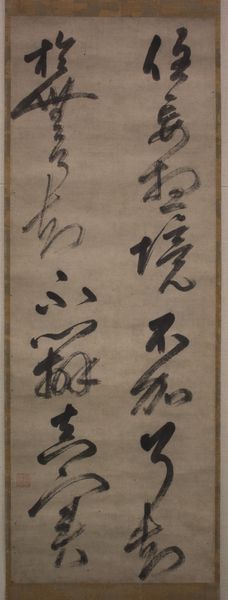

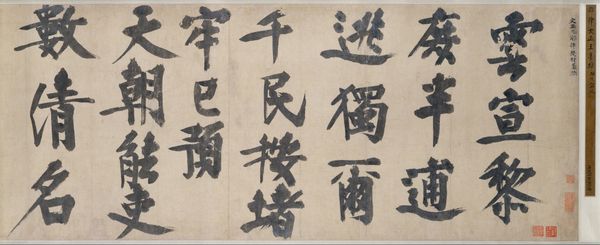

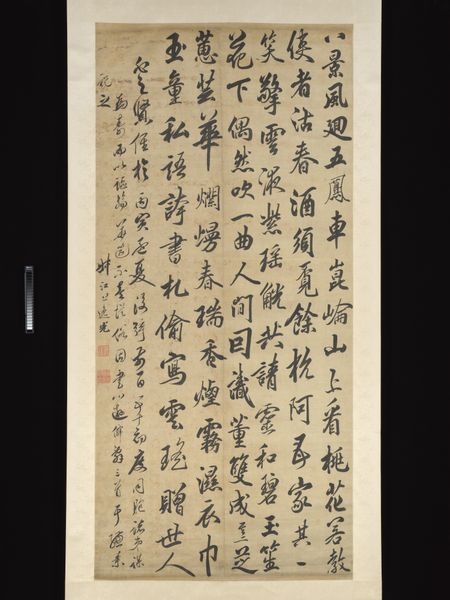

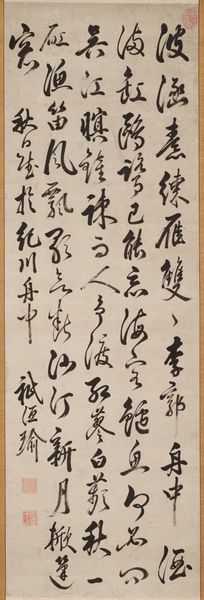

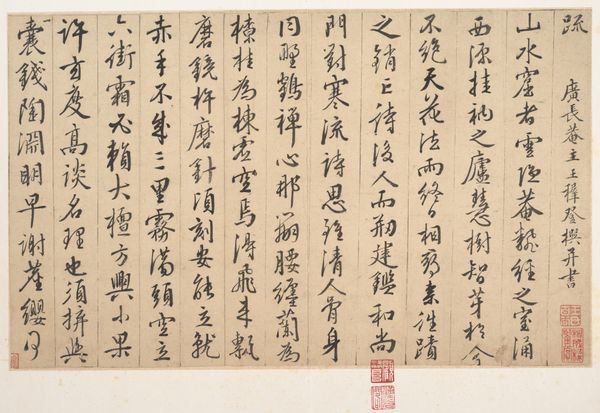

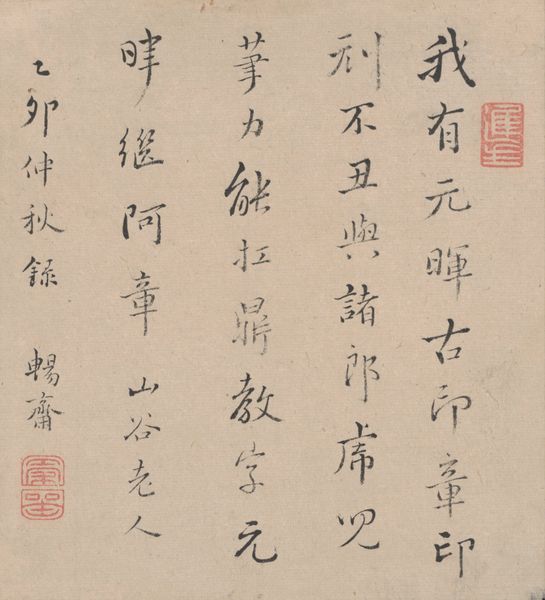

paper, ink

#

asian-art

#

paper

#

ink

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: H. 63 1/4 in. (160.6 cm); W. 18 11/16 in. (47.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

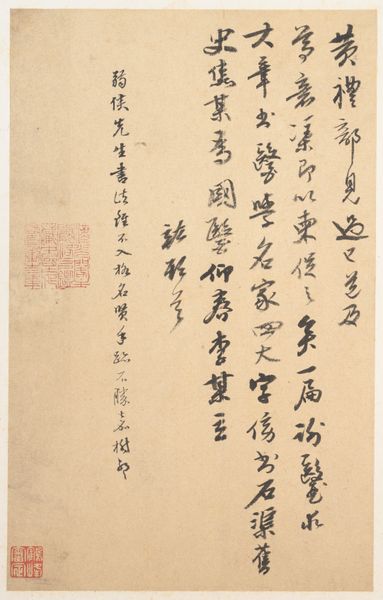

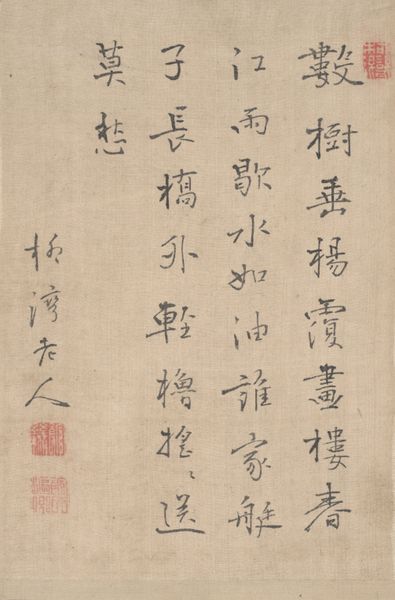

Curator: Here we have Zha Sheng's "Poem on reclusion," created sometime between 1667 and 1707. It’s ink on paper, a beautiful example of Chinese calligraphy hanging in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its elegant simplicity. The characters seem to dance down the scroll, like a conversation overheard rather than a declaration. What do you think of the way he fills the space? Curator: Well, calligraphy in this period was deeply intertwined with literati culture. This piece isn’t just about writing; it reflects social ideals of withdrawing from public life to embrace intellectual pursuits and aesthetic refinement. Zha Sheng expresses a personal longing for nature, and the choice to render this on paper gives it a delicate, intimate feel, doesn't it? Editor: Definitely. It makes me want to light some incense, pour a cup of tea, and lose myself in contemplation right here. The lines are so expressive. Does the text itself tell us something about this reclusive lifestyle? Curator: Precisely! While the actual poem on reclusion speaks of finding pleasure in nature and a kind of quiet harmony, you can see its social dimensions and the role of art as communication. Editor: The strokes have a life of their own! You can almost feel the pressure of the brush as it moves across the page, thick and thin. I imagine the artist deeply involved, even vulnerable as they create. It's powerful, you know? To have such restraint and wildness. Curator: Absolutely. The careful study of masters and techniques plays an important role here. He is making choices about communicating not only words but about his entire persona in this historical context. Editor: Looking at it makes you want to trace it yourself to get a sense of that artistic choice in his line, which comes to embody an emotion of sorts. So while that desire to withdraw could be self-centered, I think his gift became how that retreat informed how he saw and represented the world for others. Curator: Indeed, that sentiment brings us back to why works like this have public roles; it serves as a source of meditative escape. Editor: It’s like a secret whispered across centuries, a reminder that sometimes the greatest strength comes from stepping back and finding your own voice. Curator: A sentiment to which we should all ascribe as we take on our modern public roles today, eh?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.