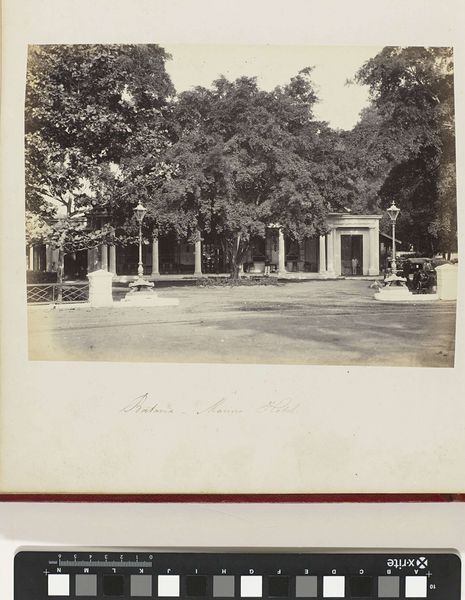

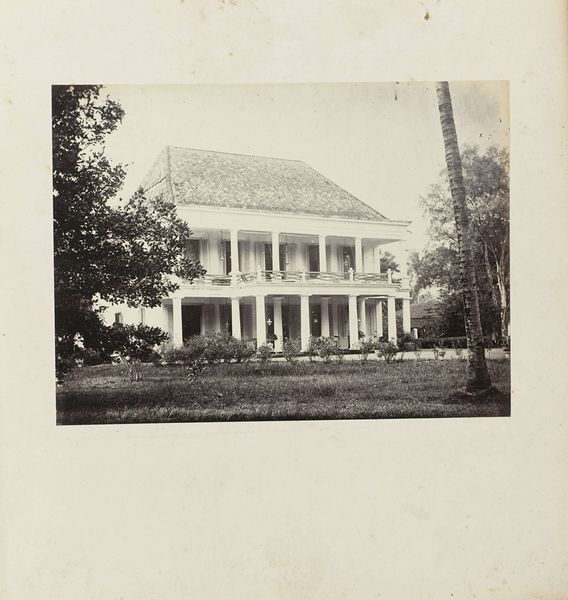

photography, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

#

realism

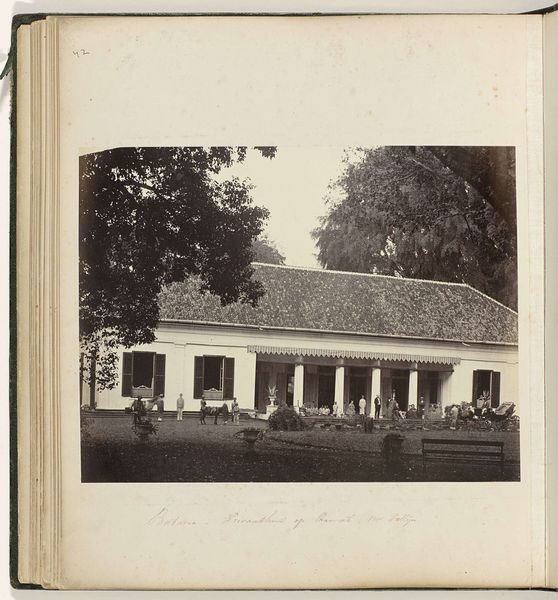

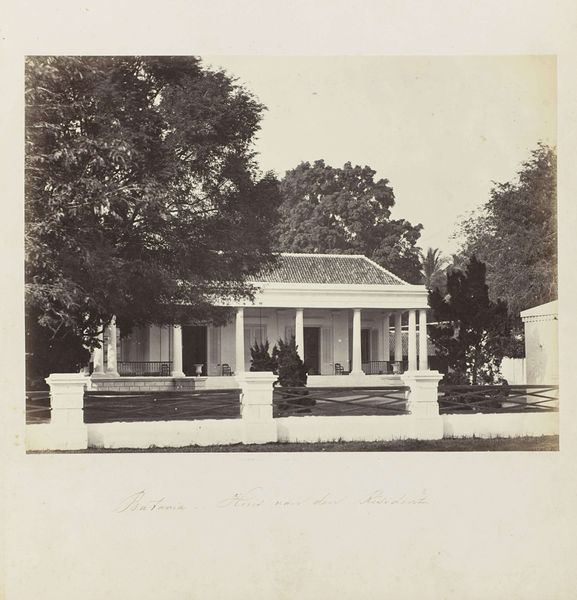

Dimensions: height 181 mm, width 240 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Woonhuis" by Woodbury & Page, dating back to between 1863 and 1866, it’s fascinating to situate this albumen print within the history of orientalism and early photographic documentation of colonial spaces. This photograph, housed at the Rijksmuseum, provides a valuable, though potentially skewed, glimpse into the social and architectural landscapes of that era. Editor: Mmm, initially, it evokes this peculiar serenity. Like a staged tableau, perhaps a little too perfectly composed. It's as though the building and its occupants are posing for history, which, I suppose, they are. The light is gorgeous, hitting the columns just so. Curator: Exactly. And we have to unpack the inherent power dynamics embedded in such images. Who is being represented, by whom, and for what purpose? Early photography, particularly in colonial contexts, served as a tool for asserting and reinforcing Western perspectives and control. How does this composition perpetuate a narrative of exoticism and power? Editor: Oh, totally, you can almost hear the colonial undertones. It feels less like a lived-in space and more like a carefully curated display of "otherness" for a Western audience. The building itself, though architecturally interesting, feels almost like a prop. Still, I find it difficult to resist a sense of the languid afternoon that it invites, with a silent, invisible chorus whispering its secrets. Curator: I agree; there’s an undeniable aesthetic appeal. But, from a postcolonial perspective, we need to challenge the romanticized, often unchallenged, depictions of colonial life presented by works such as these. We can examine the representation of the indigenous population – if present at all, the landscape, and the architectural styles depicted in the photograph. Editor: It definitely forces a double vision: appreciating the artistry while grappling with the image's socio-political implications. Art is so complicated. I suppose what lingers for me, even with all the heavy historical baggage, is the sense of space and light. Curator: I concur; the photograph embodies a convergence of art, history, and socio-political narratives. Appreciating that, as complicated as it makes the viewing experience, enables us to learn from and understand historical image-making. Editor: Yes, it encourages you to look beyond just the pretty picture. It really gets under your skin in that way. And what more can you ask for from art, anyway?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.