photography, albumen-print

#

still-life-photography

#

muted colour palette

#

natural tone

#

pictorialism

#

landscape

#

photography

#

natural colour palette

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 160 mm, width 222 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

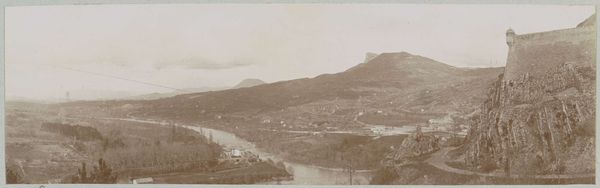

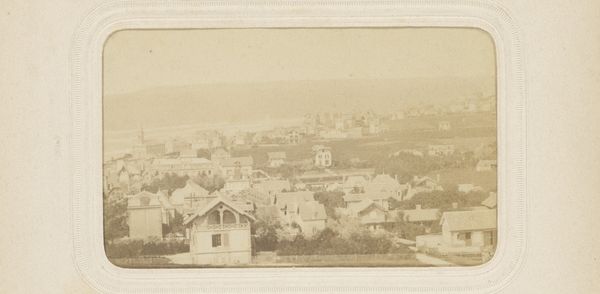

Editor: This is "Gezicht op Santa Cruz en het strand," or "View of Santa Cruz and the beach," dating from 1880 to 1920, created by Fotografia Alemana. It's an albumen print, and I'm struck by how serene and still the city looks from this vantage point. What social or historical narratives do you see embedded within this image? Curator: This photograph, like many landscapes of the period, presents a seemingly objective view. However, let's think about the act of "seeing" and who is empowered to represent a place. “Fotografia Alemana,” or “German Photography,” points to a colonial gaze. Who benefits from this seemingly neutral depiction of Santa Cruz? Consider the colonial project and its relationship to documentation. Does this photograph uphold or challenge dominant narratives of progress and development in a colonial context? Editor: So, even a picture of a landscape can be a form of colonial power? Curator: Absolutely. Landscapes weren't simply about recording what was there, but also about claiming and possessing a territory visually. The rise of photography coincided with increased European expansion. This photograph normalizes the colonial project. What details might point to the experience of the local population? Are they centered in the representation? Editor: I see... they're not. The focus is on the infrastructure and overall scene. I hadn't considered that what's *not* shown is as important as what is. Curator: Exactly! Thinking critically about visual representation pushes us to examine whose voices are amplified and whose are silenced. Editor: This makes me look at photography, and art in general, so differently now. Thanks for expanding my perspective. Curator: It’s a crucial lens. Remembering whose stories aren’t told, and asking why, empowers us to read images as political texts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.