paper

#

portrait

#

water colours

#

paper

#

watercolor

Dimensions: overall: 46.9 x 62.5 cm (18 7/16 x 24 5/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

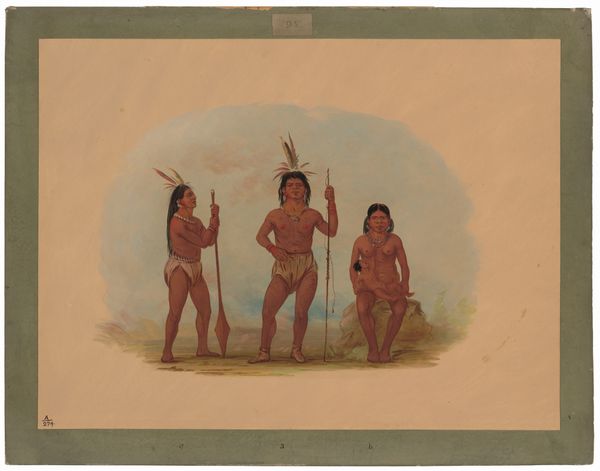

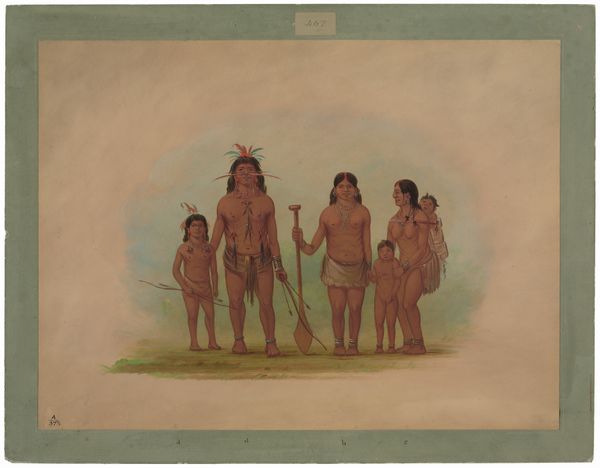

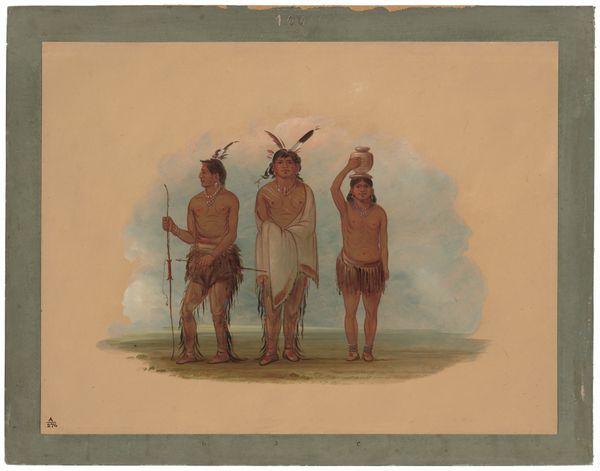

Curator: This is George Catlin's watercolor, "Ottowa Chief, His Wife, and a Warrior," created sometime between 1861 and 1869. Editor: My first impression is of fragility, a sense of things fading. The watercolor medium itself gives it this delicate quality, like a memory. Curator: Catlin was driven by a mission to document Indigenous peoples across North America, aiming to preserve their likeness and cultures amidst rapid westward expansion. It’s complex, romantic, and also deeply shaped by his own worldview. Editor: I'm interested in how the clothing and accessories are depicted. Look at the chief’s spear, and the details of the blanket around his wife. They speak to specific production practices and perhaps even trade relationships of the time. Curator: Absolutely. The clothing can also signify status. The chief's adornments and the warrior’s shield speak volumes about their roles within the community. This image participates in a long history of representing Indigenous people that we should view critically. Editor: True, we can't forget the labor involved in creating those materials – the weaving, the tanning. The materials are never neutral; they always carry social meaning. It begs the question what these items were actually like. Curator: Precisely. Catlin's project reflects both genuine fascination and a troubling power dynamic inherent in representing another culture. His intentions become particularly charged when we recognize the historical context of governmental removal. Editor: For me, understanding the physicality of these items and Catlin’s technique – how he used watercolor to portray texture and detail – grounds the piece. What was his workshop like? What kind of paper was available? These are tangible starting points. Curator: Indeed, those material considerations offer insight into the making, yet we must also situate Catlin’s aesthetic choices within the larger narrative of 19th-century America and understand this work in the context of colonial art. Editor: So it becomes a kind of historical artifact in itself, a testament to the processes and prejudices of its time? Curator: Precisely, viewed in the light of today's knowledge and understanding, it shows the complex and sometimes troubled role that representation can play.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.