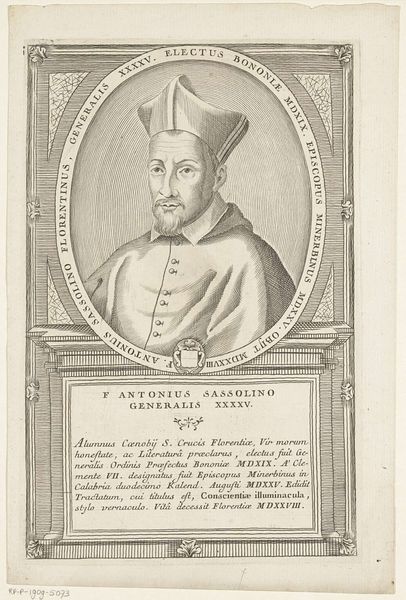

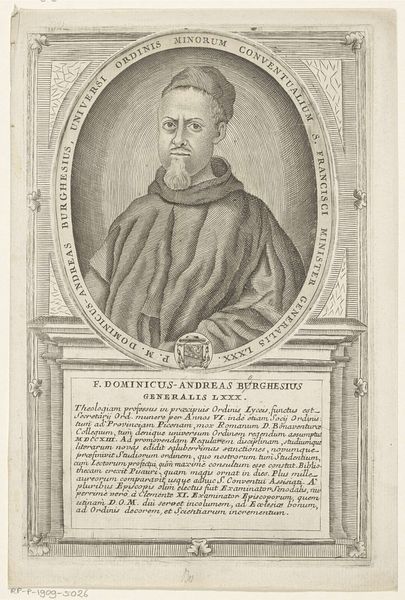

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

portrait reference

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a portrait of Andreas van Oostenrijk, an engraving by Pieter de Jode II, created sometime between 1628 and 1670. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum’s collection. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is how detailed the lines are for an engraving of this size. It's meticulous. There's a certain severity to the man's gaze, softened slightly by the texture of his clothing and beard. Curator: Andreas van Oostenrijk, as you might gather, held a significant religious and political position. This portrait reflects the power dynamics of the time. The clothing, the architecture of the surrounding frame - it all speaks to a rigid hierarchy and social order. This was during a period of intense religious and political conflict in Europe; consider how someone like Andreas might have wielded influence as a cardinal and governor. Editor: Exactly. And think about the physical act of engraving, the labour that goes into producing a multitude of these images. Who was consuming these prints? Were they propaganda? Or used more for bureaucratic reasons? It becomes part of this web of production, commerce, and political control. The lines themselves speak of meticulous, controlled work, very different than spontaneous gestures we expect from modern practices of production. Curator: These portraits circulated amongst an elite group—further solidifying power. Each impression acted as a symbol but also was a piece of propaganda that legitimized the existing societal arrangements, especially considering the Habsburg lineage and its complicated role during the Counter-Reformation. Andreas was a prominent figure with clear ambitions. Editor: It is interesting to view the material and labour that helped reinforce an aristocratic identity that defined that period. Engraving being reproducible as such would be able to influence public perception with careful crafting. It shows the interconnectedness of power structures from production to political outcomes. Curator: Seeing through this lens, it provides crucial context for discussing themes like authority, representation, and social structure during the Baroque period. This helps to bridge art-historical analyses and intersectional perspectives surrounding identity, race, and socio-politics of 17th century Europe. Editor: Thinking of the process of making these images available opens more windows onto who controlled production. What workshops did Pieter de Jode work from, what influence did their labor wield? Curator: Exactly. It reminds us that artworks, especially portraits, are always staged performances of identity, reflecting—and reinforcing—the prevailing power structures of their time. Editor: Absolutely, considering this engraving through its social construction is important, and brings further meaning and historical nuance to a piece like this.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.