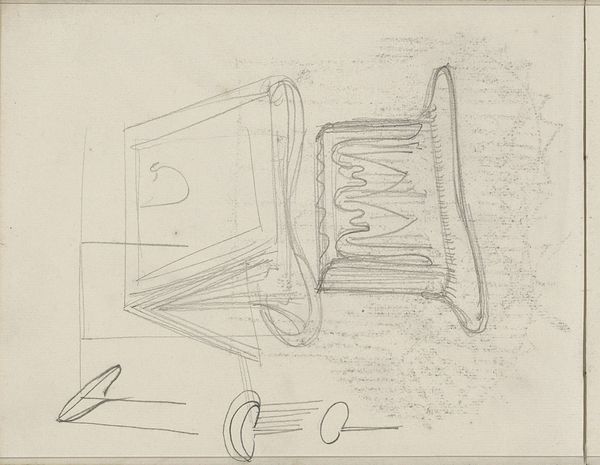

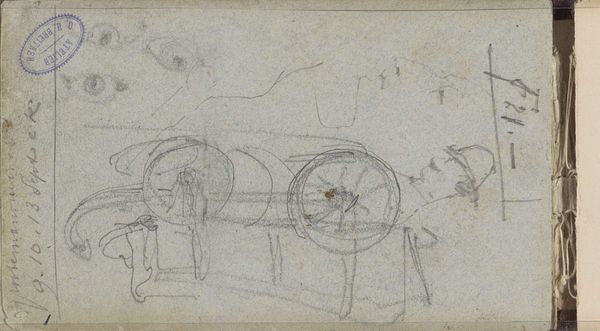

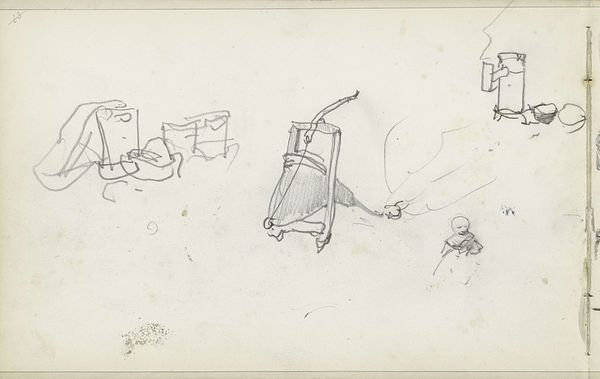

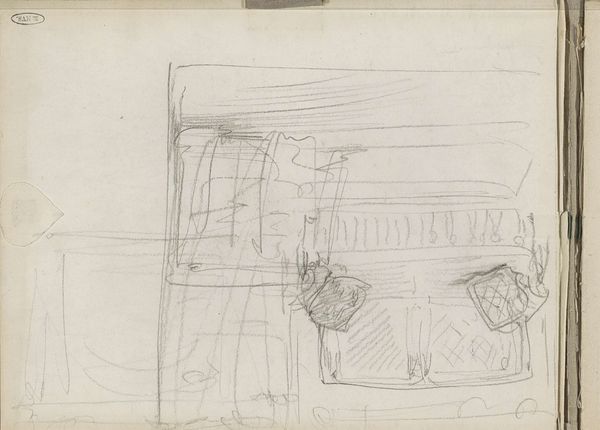

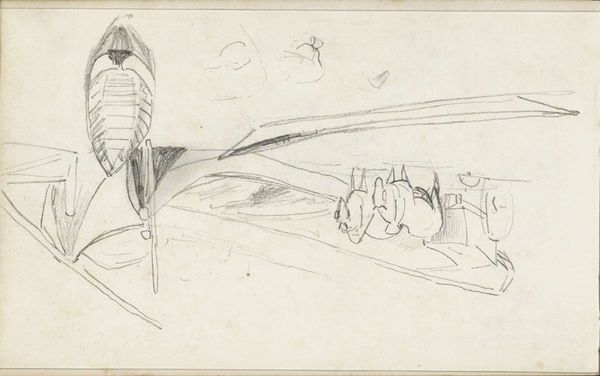

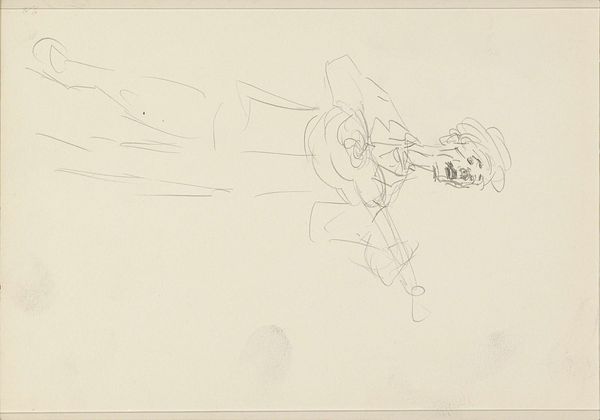

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

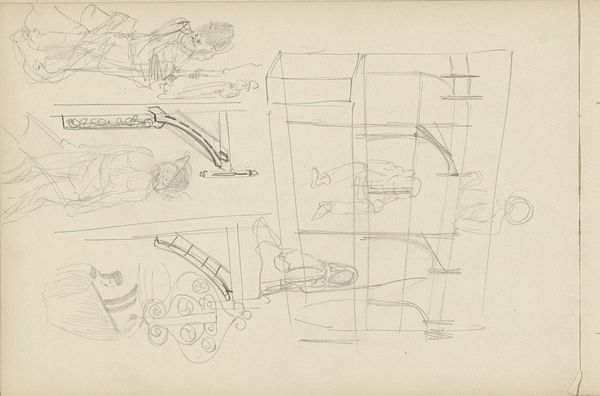

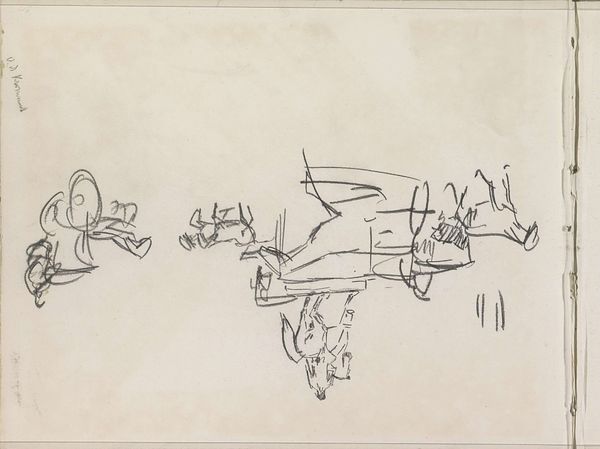

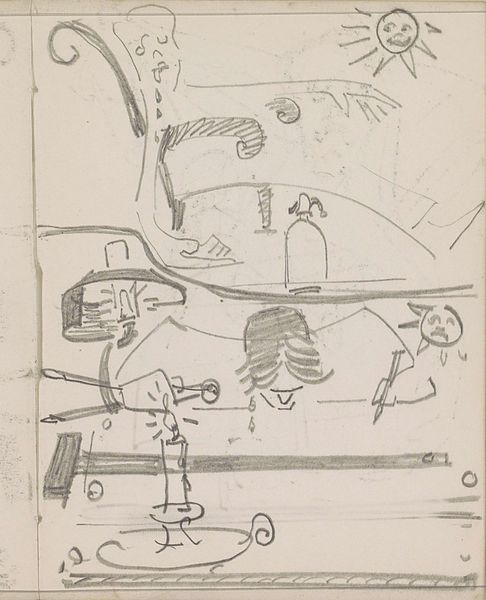

comic strip sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

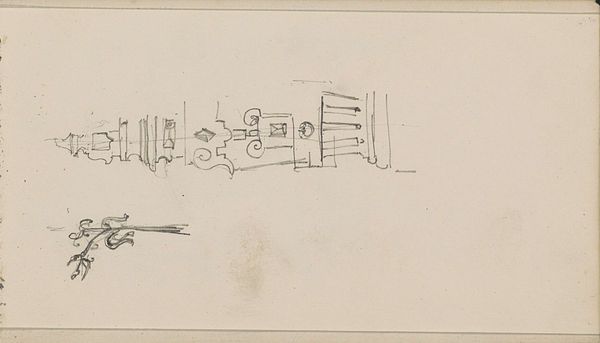

geometric

#

sketch

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

modernism

#

initial sketch

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

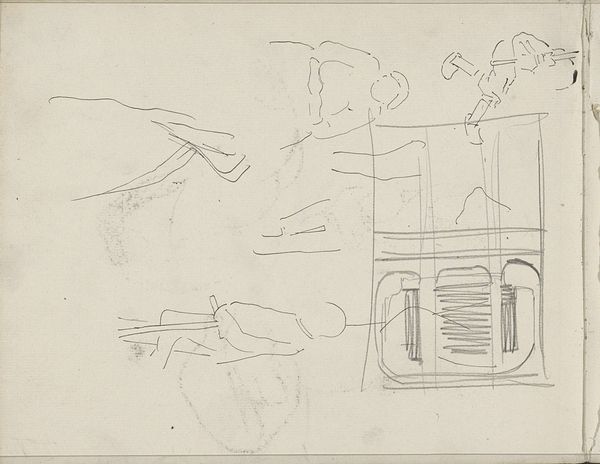

Curator: Here we have "Ontwerp voor een monumentale bank te Haarlem," or "Design for a Monumental Bench in Haarlem," a pencil and ink drawing from around 1930 by Carel Adolph Lion Cachet. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. What’s your immediate impression? Editor: Flimsy, yet imposing. The stark lines give it a sort of weight, but at the same time, you know, this is only an initial impression captured in a spontaneous moment. There is an interesting intersection here of industrial aspirations married with artistic imagination. Curator: Precisely! The use of pencil and ink – humble, readily available materials – points to the work’s function as a preliminary sketch, a starting point for what could have been a very solid, literally concrete public amenity. The materiality is really where its meaning resides, highlighting the creative process and Cachet's vision of public design for a city. Editor: And speaking of public… doesn't this form trigger a certain nostalgia? Benches have always served as meeting places, locations of pause and contemplation. Haarlem citizens, sharing the same symbolic public space, literally supported and embraced by art and civic structure. Curator: Yes, though, knowing what we do about modernist movements of the period, the lack of embellishment isn't arbitrary. It's part of a broader design ethos where form follows function, where ornamentation is eschewed in favor of utility. It is about production. Who made the actual benches, from what materials, and were they available to all of the populace, regardless of class or wealth. Editor: Perhaps. But doesn’t that spareness become a sort of symbolic statement in itself? An assertion of progress, maybe? The simple geometry suggests a collective move forward… the rejection of a cluttered past in favor of something clean, new and optimistic? The bench becomes the visual icon of societal betterment. Curator: Certainly. It's hard to separate the social context of this piece. Modernism always implies both optimism and the availability of these designs and improvements to all segments of a population... however, there may have been a separation from that initial aim, a question about that vision and availability. This adds complexity to such designs. Editor: Precisely. Ultimately, by exploring both its construction and symbolic dimensions, we begin to appreciate just how much history and hope can be embedded in something as simple as a bench sketch. Curator: Absolutely. A simple sketch it may be, but one pregnant with process, societal aspiration, and meaning when properly assessed!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.