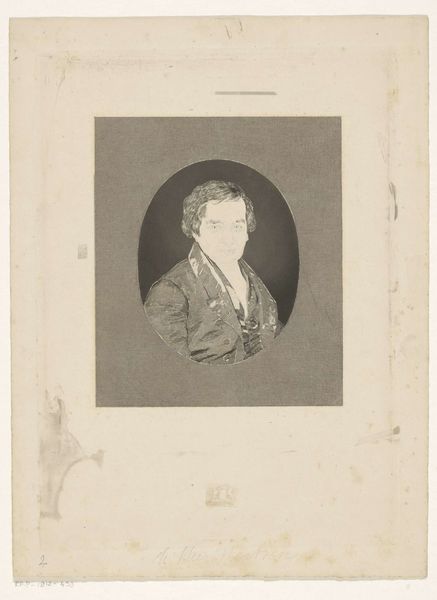

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 423 mm, width 328 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

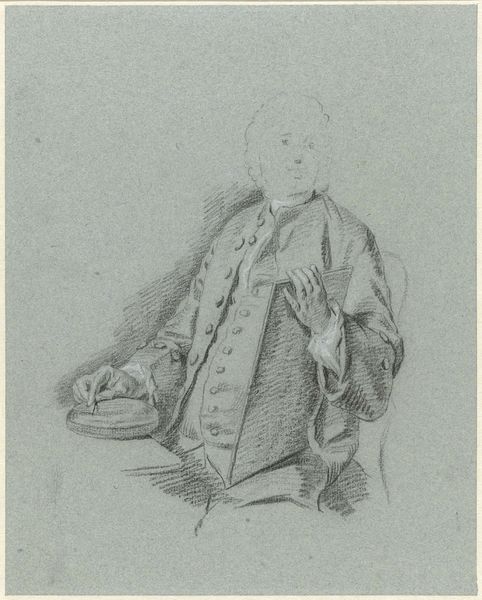

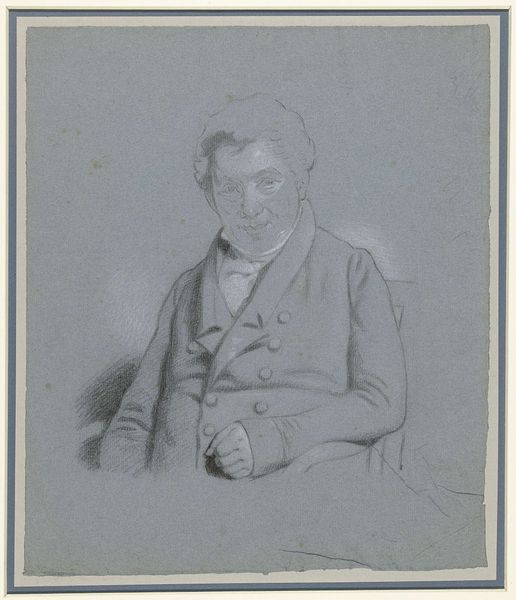

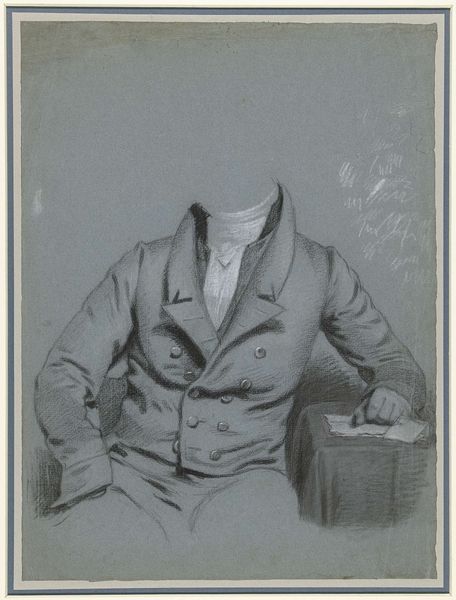

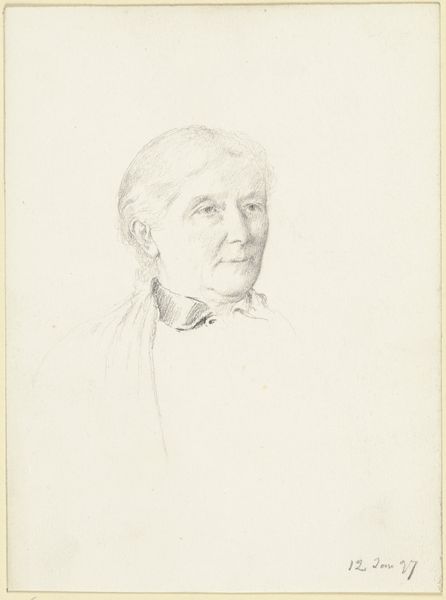

Curator: Welcome. Today, we're observing "Portret van onbekende heer," or "Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman," created between 1774 and 1837. Charles Howard Hodges rendered it using pencil. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately striking is its unfinished quality and overall melancholic air. There's a tentative quality in the linework that evokes both vulnerability and pensiveness in the subject. The negative space surrounding the subject is prominent, adding to that isolation. Curator: It's precisely this tentative quality that draws me in. The visible pencil strokes and corrections almost reveal the artist's thought process—the search for the subject's likeness and personality. Pencil as a medium lends itself so well to these nuances, creating an intimate connection. We see the underdrawing and pentimenti. Editor: And what does it mean that he is ‘unknown,’ a blank slate? While seemingly a traditional, realist portrait, his anonymity opens space for interpreting the portrait through lenses of class and social power. This man would’ve belonged to a particular socio-economic stratum of Dutch society. He wears the costume of wealth, despite his ‘unfinished’ presence. Curator: Absolutely. The sitter's clothing speaks to a specific identity, class and probably profession in his era. The vest and coat, though sketchily rendered, signal a degree of formality, yet also conformity to visual symbols expected from that strata. I also notice there’s no indication of anything religious in this portrait. Editor: I also think of gender here; the subject is in a pose we see far less of for female subjects of the era. His clothing and demeanor signify authority and presence. This portrait embodies the ways in which male figures are represented in visual art. What visual conventions define the differences across gender? Curator: The power of art is precisely that—in the hands of an iconographer such as Hodges, traditional markers of identity become powerful signifiers of so much more. Each choice of angle, costume, gaze speaks volumes even across time. The cultural memory conveyed is fascinating. Editor: Right, even this unfinished piece speaks volumes. It makes one consider not just the individual but the societal constructs they occupy, their positionality to power and norms within history. The imperfection somehow reveals everything. Curator: Indeed, this artwork functions as both historical document and a point of departure for thinking critically about visual culture and continuity. Editor: An apt way to reflect on what remains unseen as well as seen within visual culture. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.