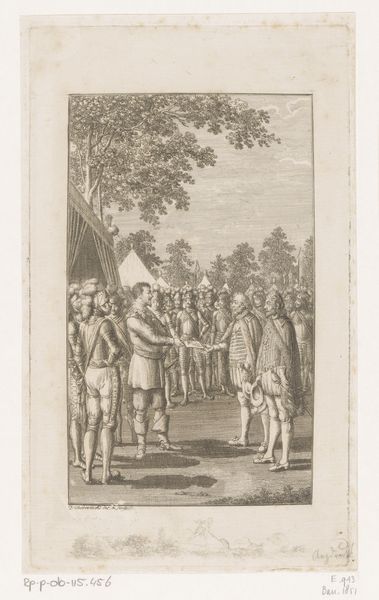

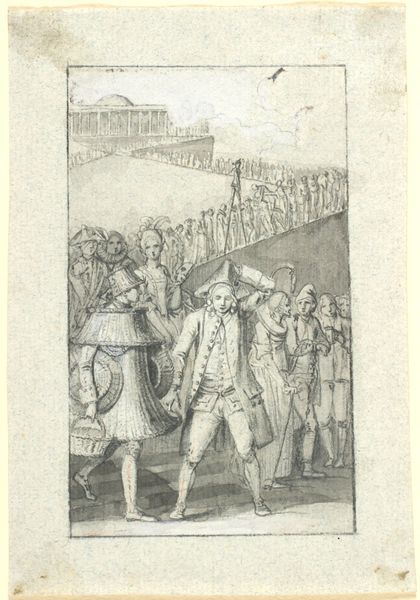

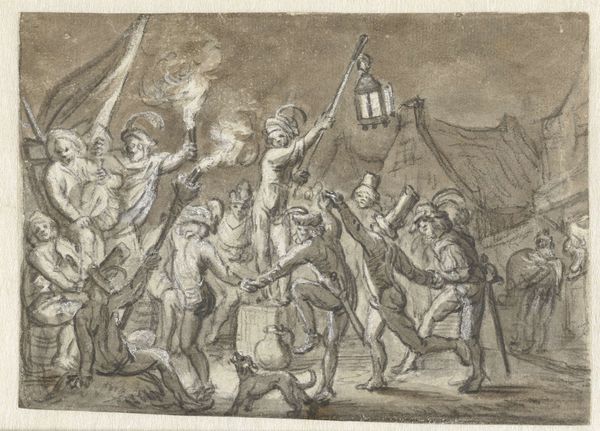

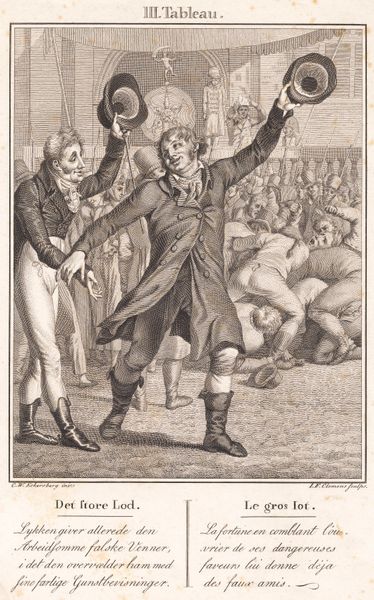

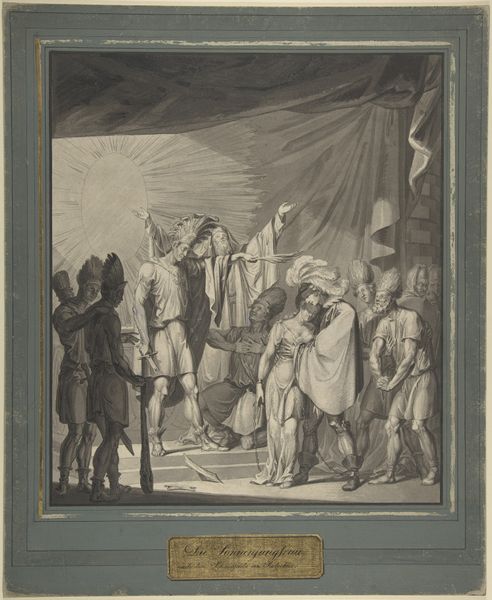

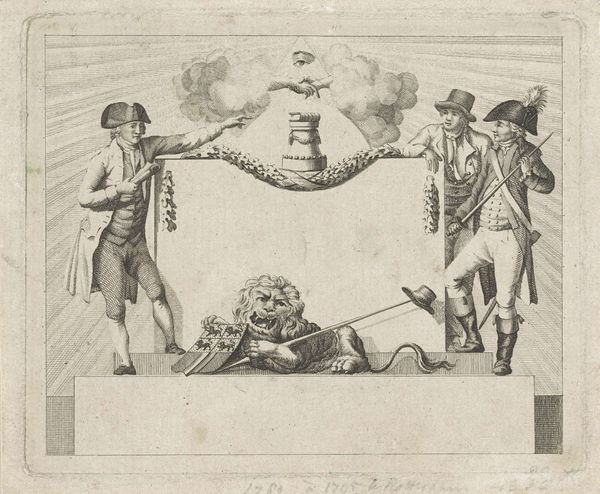

The Surrender of Earl Cornwallis (Lieutenant General of the British Army in North America) to General Washington & Count De Rochambeau, on the 19th of October, 1781 1781 - 1783

0:00

0:00

drawing, print

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

pencil drawing

#

coloured pencil

#

soldier

#

pen-ink sketch

#

men

#

watercolour illustration

#

pencil art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed and inlaid): 6 15/16 x 4 7/16 in. (17.7 x 11.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have an interesting print titled "The Surrender of Earl Cornwallis (Lieutenant General of the British Army in North America) to General Washington & Count De Rochambeau, on the 19th of October, 1781", created between 1781 and 1783. Editor: It's stark, almost austere. The somber grayscale palette and the sheer number of figures involved—it lends a sense of weighted significance, doesn’t it? What’s it made from? Curator: The work is rendered as a print, with details suggesting pencil work on toned paper, watercolour illustration and pen-ink sketching. Editor: Knowing that it's primarily pencil sketch alters my view of its intentionality. Was this intended as a preliminary study for a larger painting or a work unto itself, disseminated via printmaking to shape public opinion about the event? Curator: The socio-political ramifications are certainly central. The image, displayed now at the Met, depicts a pivotal moment in the American Revolution. But let’s consider whose story is amplified here. Washington stands tall, almost regal, receiving the literal surrender, while Cornwallis is portrayed with evident defeat. Editor: Absolutely, this is visual rhetoric at its finest, framing the birth of a nation through the symbolic act of relinquishing arms. Looking at those flags and drums, these are the spoils of war and tangible expressions of power dynamics, signifying a shift in global influence. The act of creation, of printing these images, extends the battlefield beyond the physical space to the realm of perception, disseminating a specific narrative. Curator: And that narrative touches upon themes that still resonate today: resistance, liberation, and the very construction of national identity. This event has been immortalized through meticulous reproduction, transforming historical actors into icons within a broader narrative of political and social change. It causes us to reflect on the concept of historical truth and the role of image making within ideological frameworks. Editor: Thinking about the labour involved—the papermaking, the engraving, the inking—it reinforces the revolutionary spirit embedded in the American project, which can be understood as a collective exertion of individuals working toward liberation, a sentiment that transcends mediums and movements throughout history. Curator: So while we're looking at what seems like a static image from the late 18th century, its materiality connects it directly to foundational social and political ideals. Editor: Yes, its value resides not just in historical documentation, but also its ability to engage us in the perpetual reimagining and reassessment of cultural values and revolutionary movements throughout history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.