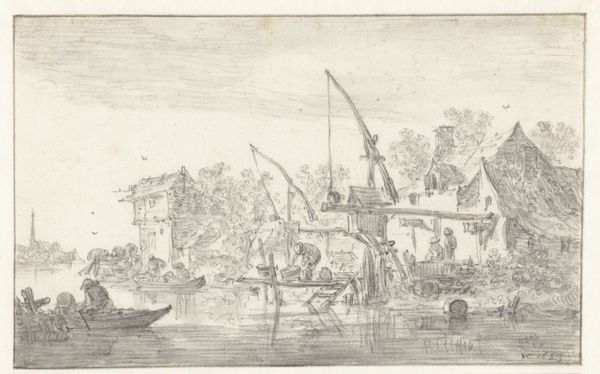

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

realism

Dimensions: height 174 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

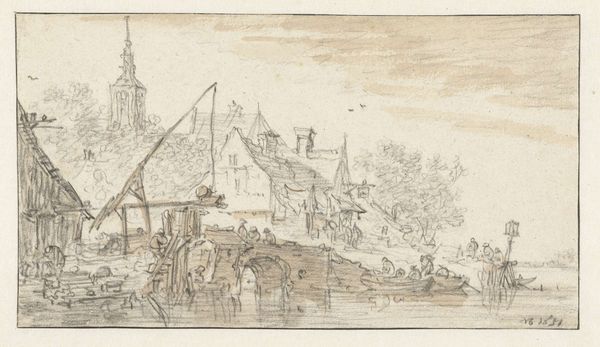

Curator: We're looking at Salomon van Ruysdael's "River Landscape with the Walls of a City on the Right," a drawing that likely dates sometime between 1610 and 1670. Editor: My initial impression is one of serene melancholy. It's a muted scene, all in ink on paper, which gives it this faded, almost dreamlike quality. Curator: Right, and focusing on that ink, you see how skillfully Ruysdael employs varied washes. It’s almost photorealistic but in the humble form of a drawing, made possible through trade of specific supplies and skillful workshop practices to train skilled draftspeople. Think of the labor involved to grind those pigments, treat the paper to accept the ink… It all speaks to the social underpinnings of art production at the time. Editor: Absolutely, but I also see a societal portrait within the landscape. Consider the walls of the city—a clear delineation between inside and outside, protection and exclusion. This image raises questions about class, access, and the power dynamics inherent in urban planning. The workers shown in the lower left corner tell the story of who labors in the landscape and whose access is dictated by the control of goods transported across it. Curator: True, the city walls physically embody those societal structures, controlling access to materials and goods crucial for its maintenance. Van Ruysdael, like other Dutch Golden Age painters, captures a very specific moment in the history of their culture, one driven by intense economic and material transformation that in turn shaped urban development, artisanal production, and global commerce. Editor: I see a narrative beyond mere representation. This piece prompts us to contemplate the implications of the era’s sociopolitical context, specifically the impacts of a bourgeoning merchant class on marginalized populations whose physical labor allowed it all to prosper. And whose perspective—namely wealthy merchants—was granted a voice via images like this, while excluding laborers? Curator: The beauty here is how a seemingly straightforward landscape can prompt a material reading, connecting art-making processes to labor and market economies. Editor: And by acknowledging the sociopolitical forces and how these histories ripple into our present. Curator: Ultimately, the drawing is both beautiful and unsettling in the questions it provokes. Editor: Precisely. Ruysdael invites us to look closer, to ask, who does this landscape serve?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.