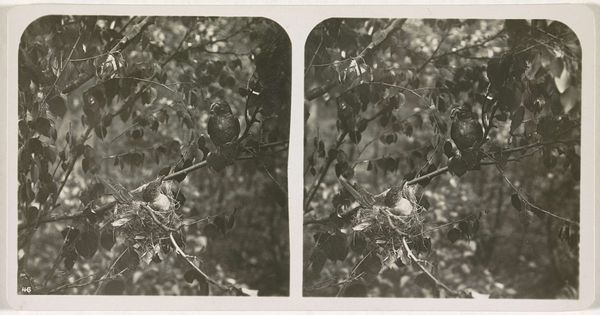

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

still-life-photography

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

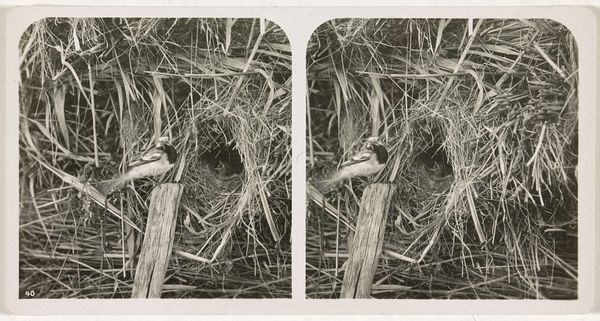

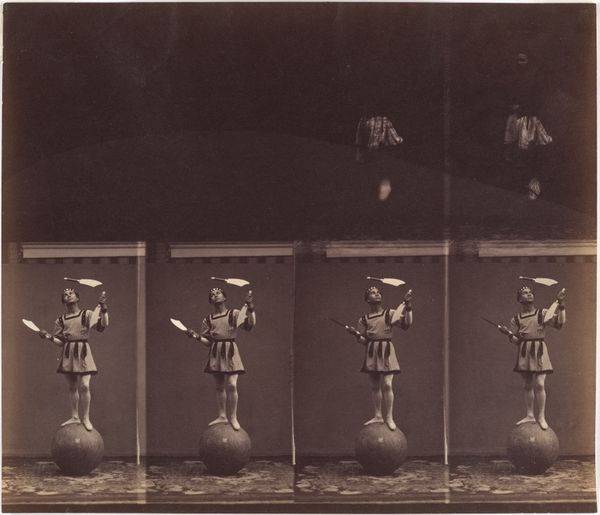

Curator: This gelatin silver print, dating from around 1870 to 1940, is titled "Twee koolmezen bij voederhuisje"—"Two Blue Tits at a Feeding House," created by Adolphe Burdet, and it is currently held in the Rijksmuseum's collection. What's your immediate take on this quaint scene? Editor: There's an intimacy to the composition despite the rigid, symmetrical framing of this stereo card. The textures in monochrome – the feathers, the woven feeders – give it a tangible weight. It feels almost like a still from a documentary, if a bit staged. Curator: Indeed. Burdet's use of the gelatin silver process allows us to explore the fine details of the natural materials. The production itself is interesting: making photography to look like observation. Look at the construction of the feeders—these elements show human labor, contrasting the “naturalness” that many perceive in landscape and nature photography. It prompts considerations about human intervention in the environment even back then. Editor: Absolutely. The play of light on those crafted textures is exquisite, almost sculptural. The formal repetition within the image plane emphasizes a calculated construction. Notice how the framing reinforces a symmetrical stillness? I can nearly feel the hushed anticipation. Curator: Considering the probable consumption context, the print's reproducibility as part of a stereo card enabled the middle class to "own" these experiences of “nature,” contributing to the development of nature-oriented ideologies in the late 19th century. It’s both nature observation and manufactured product. Editor: True, but viewing the print today, detached from its mass-produced origin, allows us to reassess it aesthetically. Those small details, like the hanging strands or the pose of each bird, now carry significant aesthetic weight. It creates this serene mood. Curator: The act of providing for these birds—constructing these feeding stations—what does this labor of “caring” communicate to the people consuming this image? What are they supposed to then reproduce as productive labor or social practice? Editor: Interesting considerations, and while I acknowledge that angle, I find that focusing too much on its consumption history obscures the delicate aesthetic sensibility visible even now. Curator: It’s through interrogating those social layers that the aesthetic itself is revealed, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Perhaps. This image makes you ponder these things beyond aesthetics alone. Curator: Precisely.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.