print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

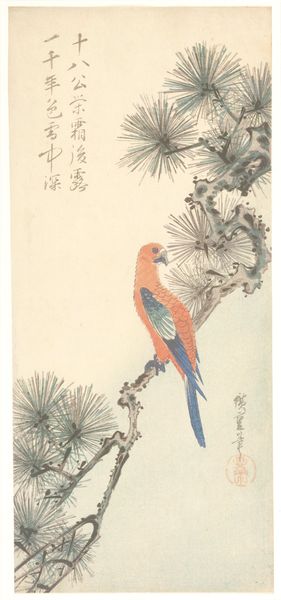

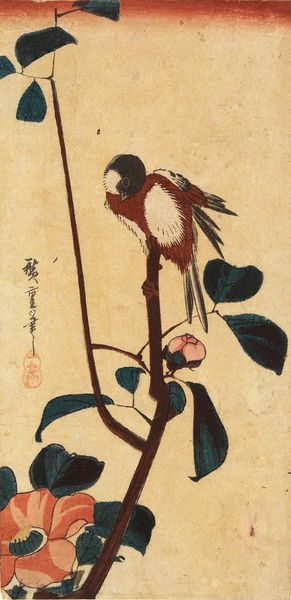

Curator: This captivating woodblock print before us is titled "Macaw on a Pine Branch," created by Utagawa Hiroshige sometime between 1840 and 1844. Editor: The composition is striking. I am drawn in by the balance created by the branches and the way the pinks and greens of the macaw just pop against the monochrome background. Curator: It's more than just aesthetic; it also engages a socio-political dialogue around the concept of "exoticism". During that period, Japan was cautiously opening to the world after a long period of isolation, and the macaw itself functions as an imported commodity. It signifies this influx of foreign elements and perhaps reflects a moment of internal grappling with this introduction of outside influences. Editor: I appreciate your point; I would only suggest also noting how skillfully Hiroshige uses negative space, giving weight to individual details like each pine needle, without overwhelming the central figure, and that helps draw your eyes exactly where he wants them. Curator: And indeed that bird could serve as a metaphor for displacement and forced adaptation. Perhaps we could think of the parrot representing subjugated voices of other lands which are compelled to exist outside their natural ecosystem for the gaze and enjoyment of the few... This allows one to interrogate questions about power, visibility, and marginalization—specifically concerning how certain life forms are valued above others in visual representation. Editor: Yes but, irrespective of cultural readings, it is still beautiful to note how each shade contributes in terms of color relations. And while these themes that you touch on can add valuable perspectives, do they overwhelm our objective appraisal of the artist's skill with form and composition? Curator: I would argue not. Thinking about the politics *behind* such exoticizations isn't an erasure of form. It enriches our perception. To examine it within cultural discourse and history empowers our visual experiences and understandings—illuminating dynamics between display and reality that might stay buried. Editor: Fair enough, it offers a fresh context for understanding the artist’s worldview, doesn't it? It just struck me, examining it once again: how even in seeming "neutrality" as simply an aesthetically pleasing scene can contain multifaceted messages about belonging. Curator: Exactly; "neutrality" is the grand illusion. The arrangement, medium, and setting, are always indicative of underlying positions which we must decode consciously so that they no longer work subconsciously upon society and ourselves. Editor: Very insightful—and seeing things under that light is much better, as this particular period represents an inflection point, one can also appreciate more clearly how it continues resonating to our very modern lives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.