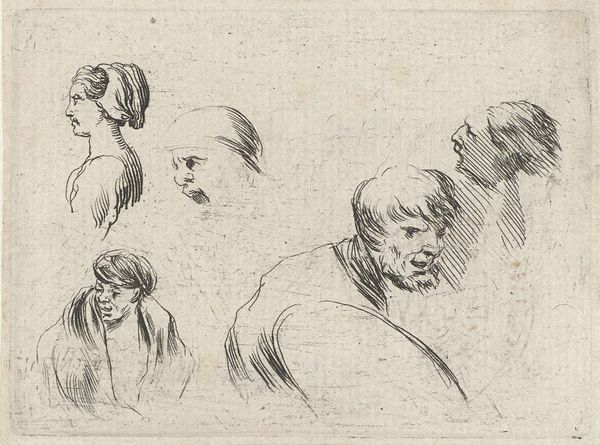

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil

#

northern-renaissance

#

profile

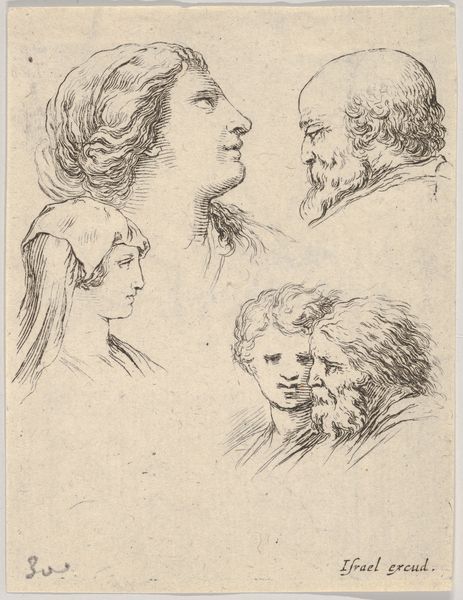

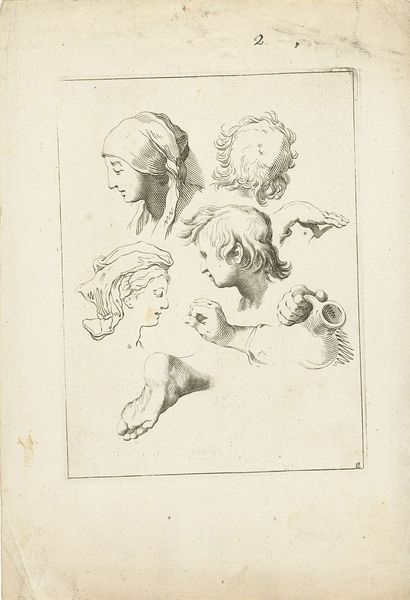

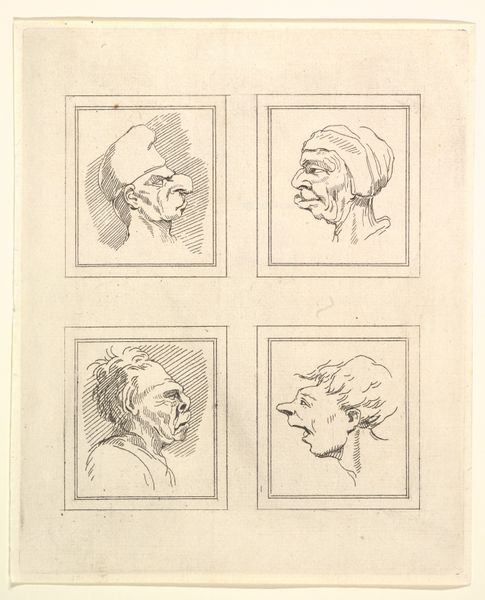

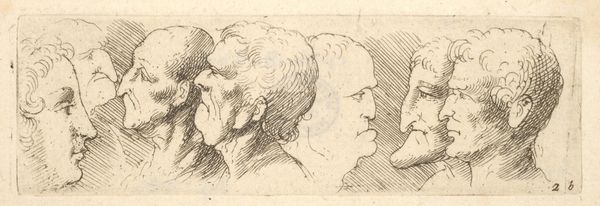

Dimensions: height 72 mm, width 57 mm, height 65 mm, width 54 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have a drawing entitled "Heads of Men and Women". Its authorship is unattributed, filed as anonymous, and its creation dates sometime between 1620 and 1664. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the economy of line. There's something almost forensic in the detail given with so few strokes of what appears to be a pencil. The arrangement too – like studies laid out on a single sheet. Curator: Precisely. Its medium of pencil and paper suggests that it functioned as preparatory work. Note the groupings, each block showing faces in conversation and offering different viewpoints. The very nature of this work invites the question of how workshops of the period approached image production, specifically how artists reused or revised images in response to changing patronage and cultural contexts. Editor: And how readily these portraits borrow from the well of classical imagery! See the Roman noses, the hairstyles… But more than the figures themselves, I find myself drawn to the surface itself – the evidence of its making. Was it commonly accepted in this period that drawing and its inherent gestural activity be used in social practices? Curator: Not universally accepted, but growing. This sort of drawing was intended for close looking – either by the artist for later work, or for an audience educated enough to find value in these ‘rough drafts.’ We must acknowledge the significance of art being intertwined with class, which promoted social values regarding what defined good taste. Editor: Thinking about its afterlife, the paper, the pencil, they give a distinct feel. Not one of preciousness, but functionality, of the work existing as just another cog in some larger cultural or material machine. Curator: Exactly. It’s in drawings like these, beyond the showpieces of the era, that we find clues to the cultural practices that shaped the art we revere today. This exercise of viewing has opened up pathways in understanding the dynamics and evolution of portraiture throughout art history. Editor: And for me, it reminds us of the constant process of production. The images are reworked, reimagined, recycled; these heads, preserved in pencil, are part of a much wider history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.