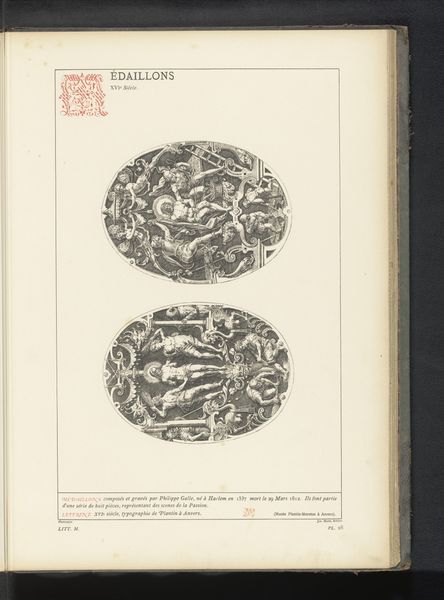

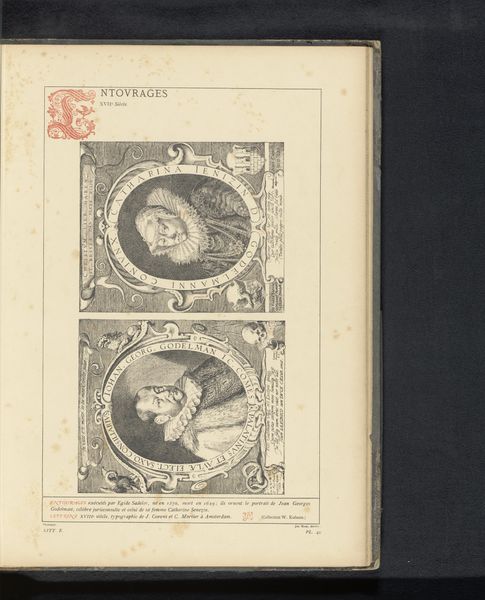

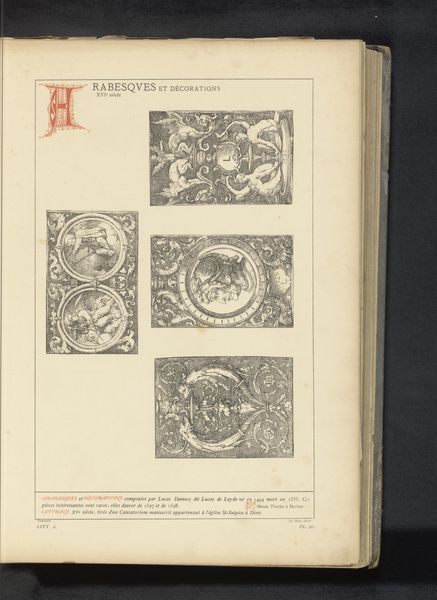

Reproductie van een prent van twee medaillons door Theodoor de Bry, afgebeeld Willem I als de voorman van de wijsheid en Fernando Álvarez de Toledo als de voorman van de dwaasheid before 1880

0:00

0:00

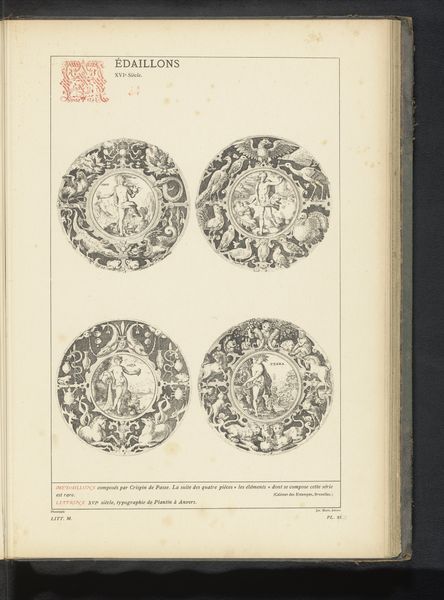

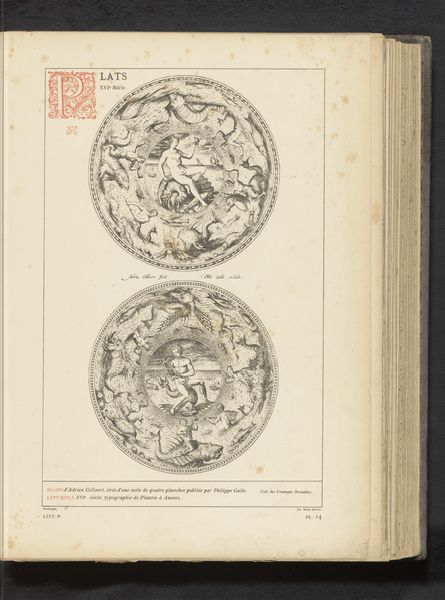

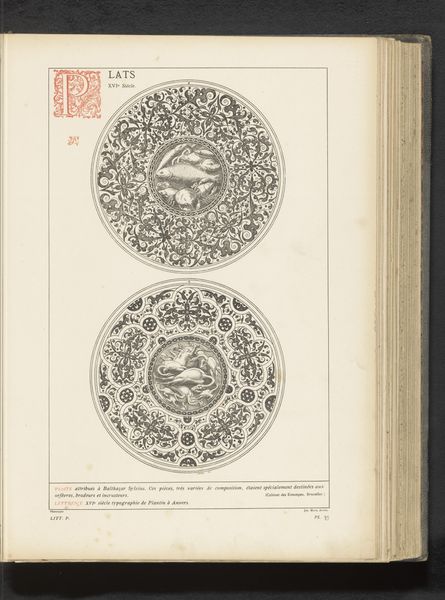

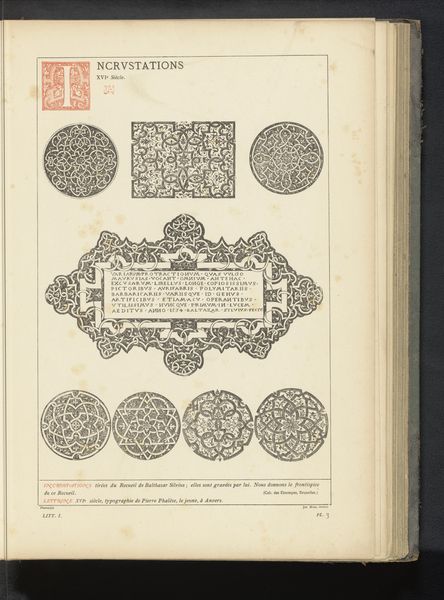

drawing, print, paper, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 339 mm, width 232 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is a reproduction of a print by Theodoor de Bry, dating from before 1880. It's titled "Reproductie van een prent van twee medaillons door Theodoor de Bry, afgebeeld Willem I als de voorman van de wijsheid en Fernando Álvarez de Toledo als de voorman van de dwaasheid," which translates to portraying William I and Fernando Álvarez de Toledo. I am immediately struck by how the print contrasts these two figures. What do you make of this visual opposition? Curator: What intrigues me here is the active role prints played in shaping public opinion. Consider the context: Willem I and Fernando Álvarez de Toledo were key figures in the Dutch Revolt. Prints like this weren't just art; they were powerful tools of propaganda. De Bry is directly engaging in the politics of imagery by presenting these two men as embodying wisdom versus foolishness, a blatant commentary on their respective roles in the conflict. What does this tell us about the potential audiences for such a work? Editor: It highlights how visual culture functioned within socio-political power struggles. Was the symbolism, and the good-vs-evil presentation of these men, easily understood at the time by a wide population? Curator: Absolutely, prints were relatively accessible. The engraving medium allowed for mass production, making these images widely available for viewing. This likely served to reinforce pre-existing societal sentiments. Beyond their distribution, the physical locations would likely have been specific; did they play any role in how the print was perceived? Editor: I didn't consider location, but perhaps the prints were hung in meeting places, almost acting as conversation starters that pushed anti-Spanish propaganda further! It's remarkable how this print was a deliberate act of historical construction and societal critique through symbolism and portraiture. Curator: Indeed! Thinking about art as active agent in a social and political dialogue like the one here provides crucial context and reveals meaning.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.