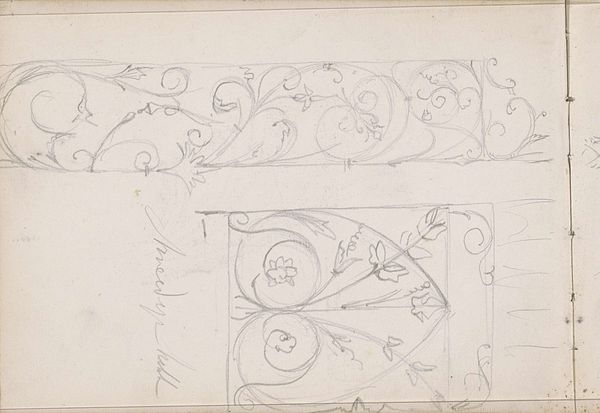

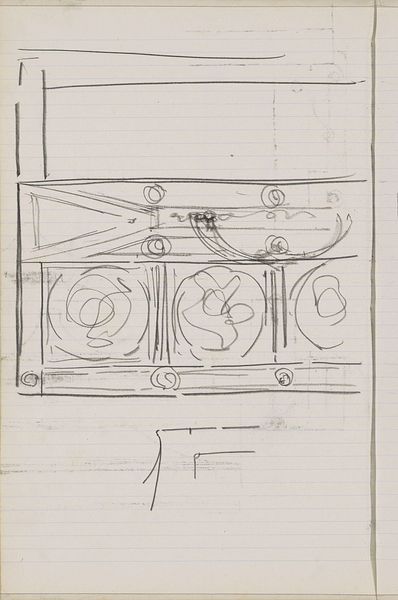

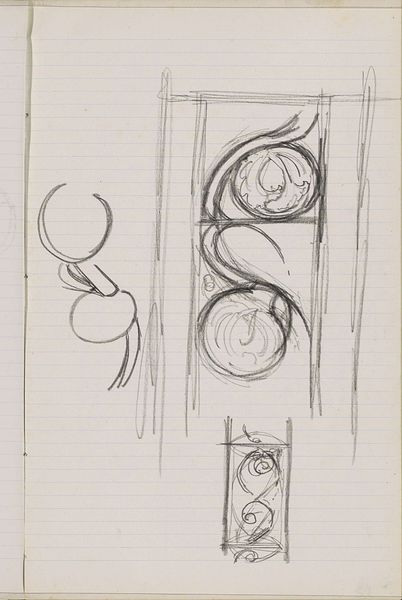

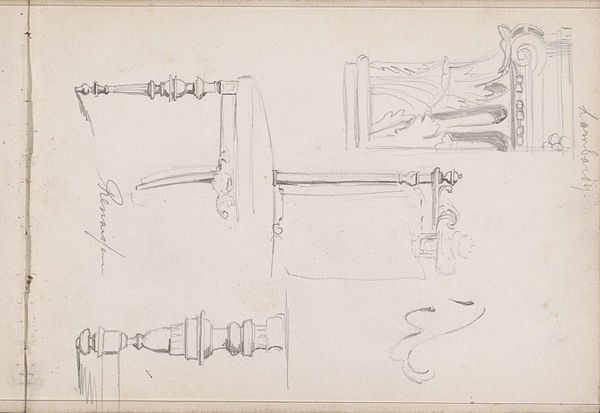

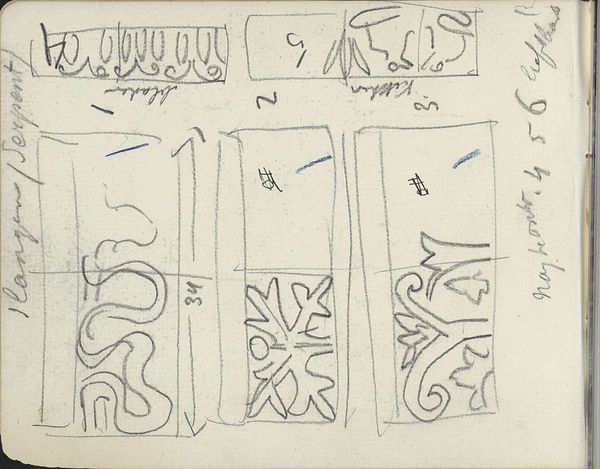

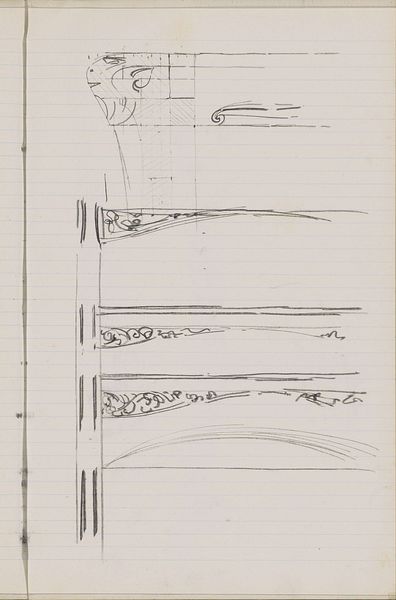

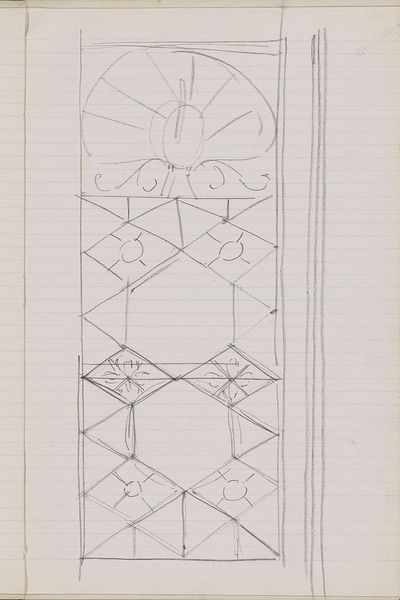

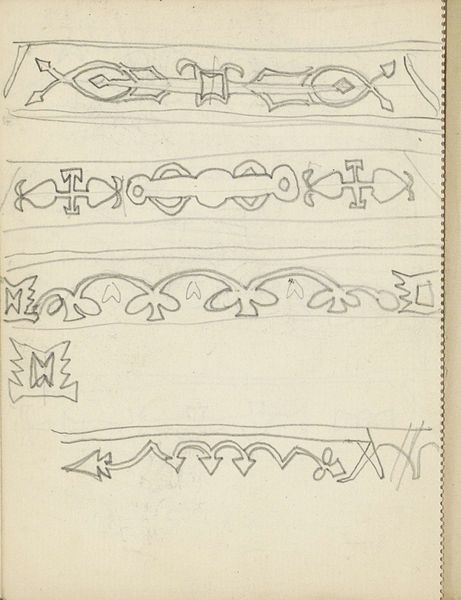

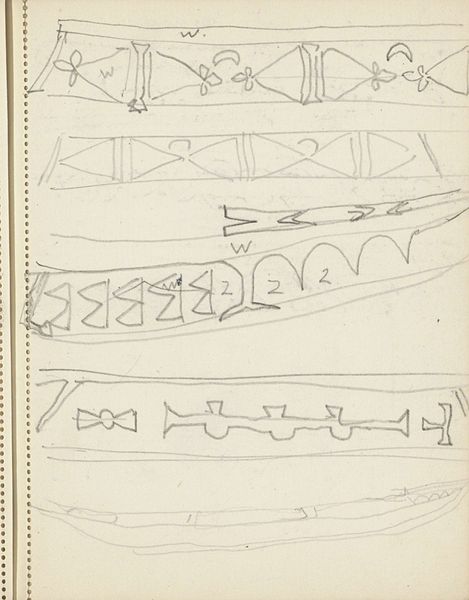

drawing, pencil

#

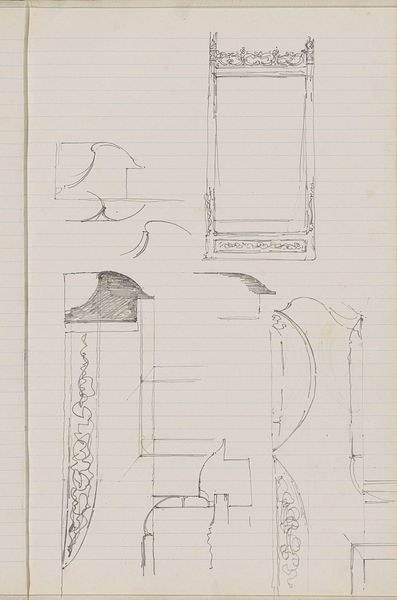

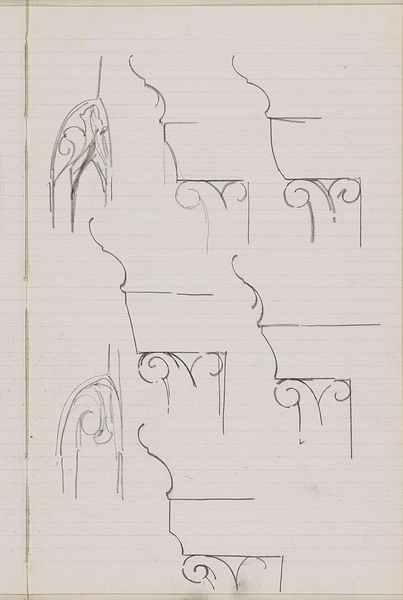

drawing

#

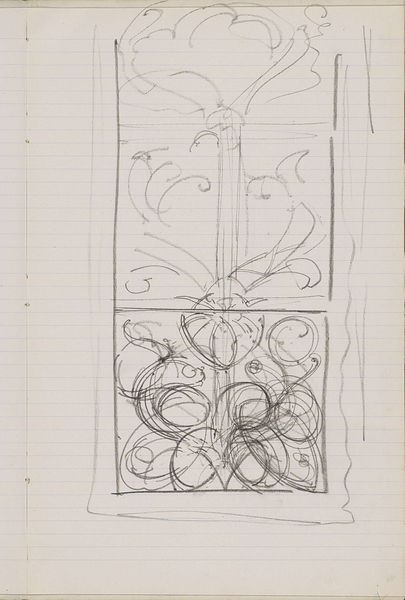

amateur sketch

#

table

#

thin stroke sketch

#

quirky sketch

#

arts-&-crafts-movement

#

form

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

geometric

#

sketch

#

pencil

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

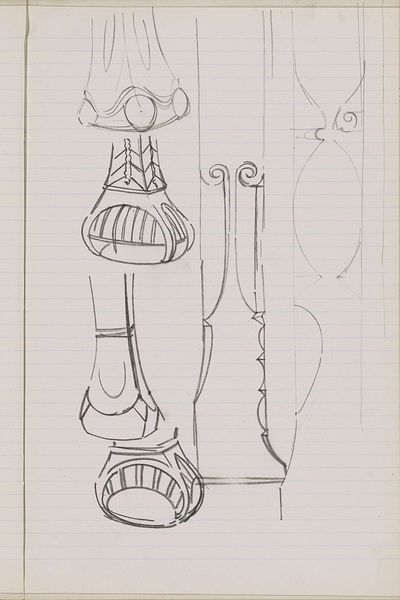

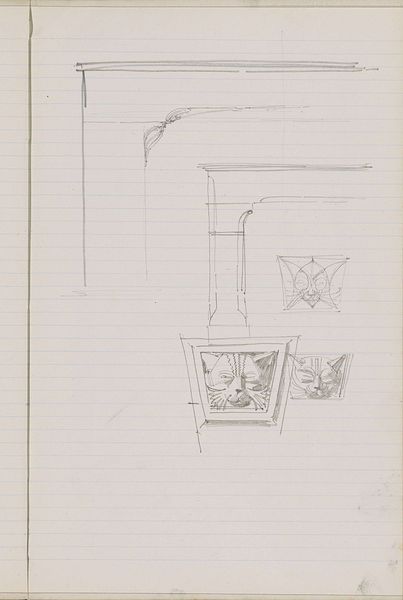

Curator: Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof, around 1901, rendered this work, "Tafelpoten en ornamenten," in pencil and perhaps a bit of ink. It currently resides at the Rijksmuseum. My first thought? It feels unfinished, raw. Editor: Precisely. There is a beautiful economy of line in the quick studies—pure form distilled onto the page. Look at the geometric breakdowns alongside the flourish of the ornamentation. It seems a clear push and pull between structure and embellishment. Curator: That tension absolutely mirrors broader societal anxieties of the time, particularly anxieties around labor and production. The Arts and Crafts movement, with which Dijsselhof was affiliated, critiqued industrialization's alienation of the worker from their craft. He was looking to elevate craft by demonstrating it as valuable intellectual property for a growing and increasingly class-based art consumer market. Editor: You're drawing out the social implications of something I saw more formally. These initial strokes are intriguing, and while, yes, we can contextualize within a social and political movement, at face value, each is such an individual formal experiment. Dijsselhof plays with symmetry, asymmetry, proportion. I love that one can visually deconstruct this as an architecture in its own right—ideas scaffolding a future. Curator: Absolutely. Dijsselhof's embrace of both geometric precision and free-flowing ornament suggests an attempt to reconcile tradition with modernity, much like we are, standing here talking about his sketchbook! Consider that his design ethos centered a belief in art's capacity to impact the lives of all, thus providing a moralizing component of domestic environments and elevating design and craftsmanship. Editor: And through this sketch we, now, almost one hundred years later, find beauty, intentionality and ultimately see Dijsselhof trying to define what would aesthetically bring harmony to functional and beautiful design. The purity of these initial designs are striking. Curator: I find myself considering these lines—almost like traces, artifacts that mark the beginning of a tangible effort to affect and enrich our shared everyday reality. Editor: I'm leaving this conversation seeing lines—lines not only forming, delineating, representing the design of potential future furnishings but a distillation of how geometric form has an intrinsic balance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.