daguerreotype, photography

#

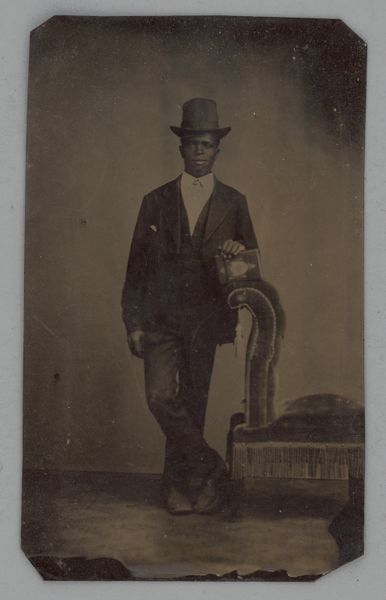

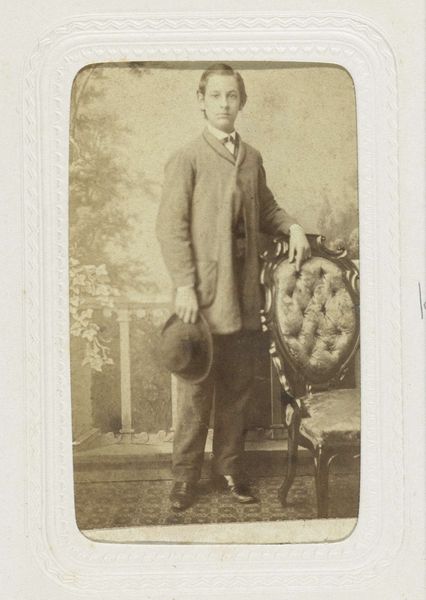

portrait

#

african-art

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

framed image

#

united-states

#

history-painting

#

realism

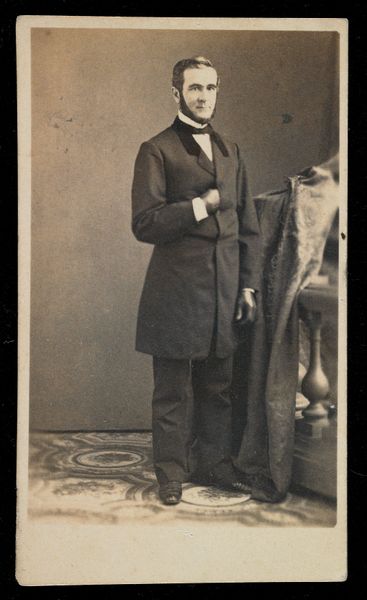

Dimensions: 10 × 5.7 cm (4 × 3 in., plate); 11 × 8.5 cm (card)

Copyright: Public Domain

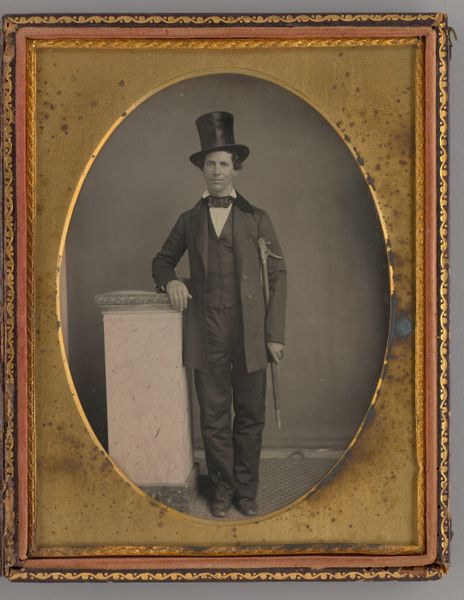

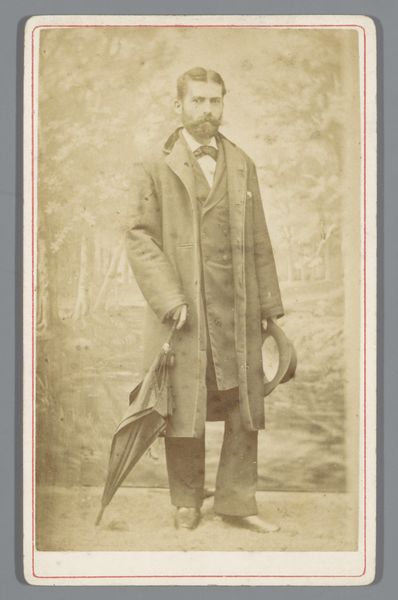

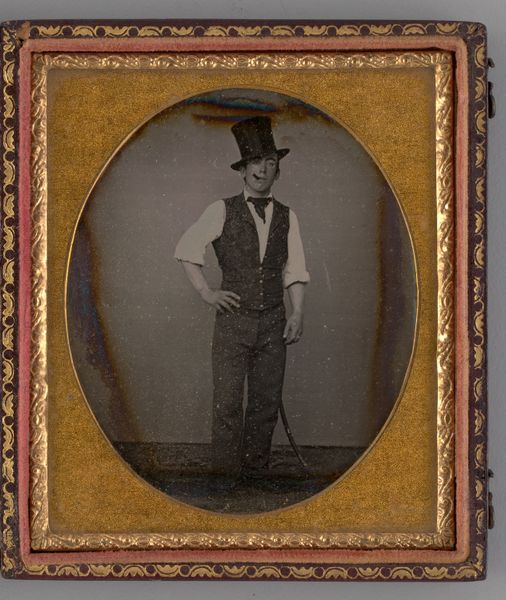

Curator: Standing before us is an untitled daguerreotype from 1880, a portrait of a standing man held in the collection of The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It's arresting—the stark formality, the man's poised gaze, the palpable materiality of the photograph itself. It whispers of a specific time and place, yet speaks to enduring themes of representation and identity. Curator: Indeed. The daguerreotype process, an early form of photography, is central to understanding this work. Consider the material constraints: the polished silver-plated copper, the meticulous chemical process, the long exposure times that would have required the sitter to remain perfectly still. Editor: And think about what it meant for a Black man in 1880 to be photographed in such a formal manner. This wasn’t casual documentation; it was a deliberate act of self-presentation. What statement was he trying to make about belonging and status in a post-Reconstruction America still marred by racial injustice? Curator: Precisely. The craftsmanship is evident in the details: the carefully tailored suit, the slight sheen on the polished floor. It all speaks to the subject's socio-economic standing, the labor involved in his appearance, and the economics of photography in the late 19th century. Access to the materials, the knowledge of the technique – all shaped who was photographed. Editor: And it's not just about access, but also about agency. He’s leaning against the chair, his stance suggesting confidence. The hat, the suit – are they symbols of aspiration or assimilation? Was this portrait meant to circulate within his community, or was it commissioned for another purpose? Curator: I am captivated by the unknown. Consider also that anonymous artists frequently worked collaboratively. How would knowing more about the photographic processes used in Black studios shift how we read this image, in tandem with labor conditions of portraiture itself? Editor: Exactly! To consider this portrait, then, it’s critical to go beyond formal analysis and examine the racial, gender, and socioeconomic structures that shaped its production and reception. What this single image reveals about broader questions of identity, representation, and resistance is so relevant today. Curator: You’ve broadened my thinking – seeing the photograph not only as an object, but a testament to its complex existence. Editor: As have you. Now I am reminded to think about the intersectionality of labor involved in photography as we seek a fuller account of identity formation, artistic production, and its complicated role within contemporary visual culture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.