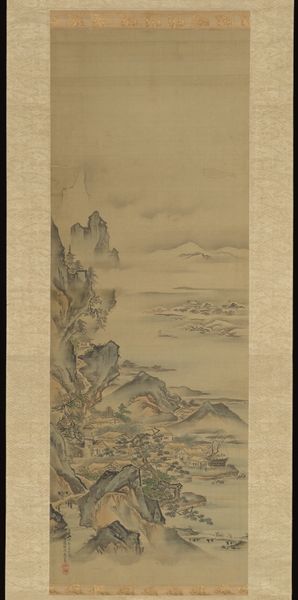

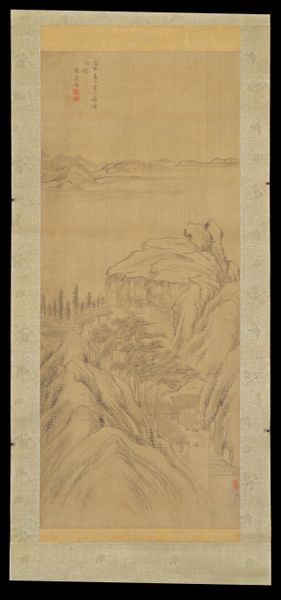

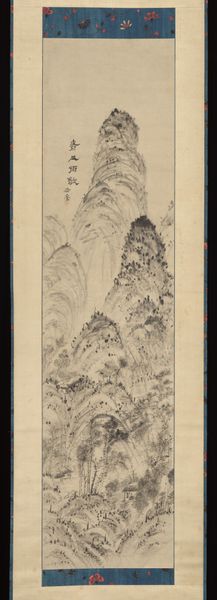

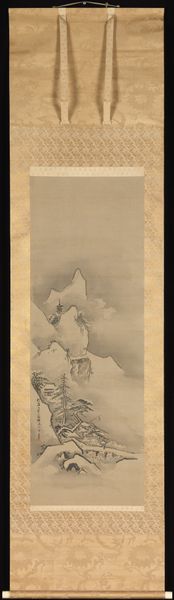

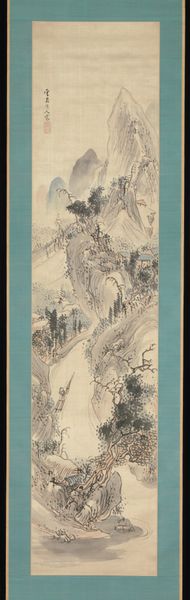

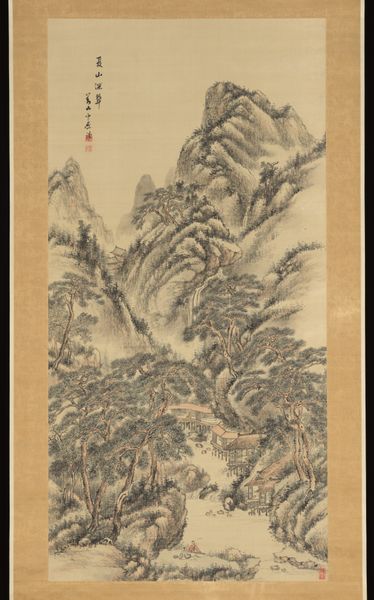

Landscape After -Solitary Fishing in a Ravine of Flowers- by Wang Meng 1749

0:00

0:00

painting, hanging-scroll, ink

#

ink painting

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

hanging-scroll

#

ink

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: 136 1/4 × 47 11/16 in. (346.08 × 121.13 cm) (image, approximately)161 × 54 1/2 in. (408.94 × 138.43 cm) (mount, approximately w/o roller knobs)161 × 57 1/2 in. (408.94 × 146.05 cm) (mount, approximately w/ roller knobs)1 9/16 × 1 3/4 in. (3.97 × 4.45 cm) (object part, each roller end)

Copyright: Public Domain

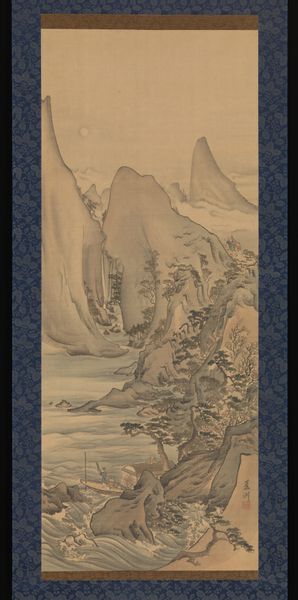

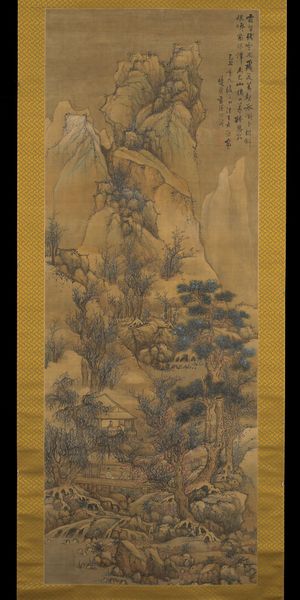

Curator: This hanging scroll before us, titled "Landscape After -Solitary Fishing in a Ravine of Flowers-" by Wang Meng, dates back to 1749. It’s currently part of the Minneapolis Institute of Art’s collection and demonstrates the profound influence of earlier masters. Editor: It strikes me immediately with its ethereal quality. The washes of ink create a soft, dreamlike atmosphere, very calming. Is this the landscape idealized, or an actual place documented? Curator: In a way, both. These scholar-artists weren't just replicating scenes, but interpreting and internalizing them, which explains the hazy ink aesthetic. We need to look at these landscapes less as geography, more as cultural and philosophical expressions, informed by Neo-Confucianism and the importance of nature as a space for contemplation. Think about the tradition of scholarly reclusion... Editor: So the "solitary fishing" becomes a loaded image, doesn't it? The very act carries themes of resisting dominant forces or ideas by choosing a path removed from society's demands. Were many of these scholar-artists dissidents? Curator: Not necessarily dissidents in the sense of outright rebellion, but many withdrew from official life. Their art then reflected their desire for personal cultivation and ethical self-improvement outside the bureaucracy. Consider, though, that their works were collected and celebrated *by* the literati! Their landscapes, although presented as a "return to nature," were consumed in very exclusive social spheres, and reproduced an inherently stratified structure of seeing and possessing. Editor: That raises fascinating questions about art's potential for both subversion and complicity. Even within the act of 'withdrawing,' class privilege and the circulation of art objects reproduce specific social hierarchies, framing what we see. Thank you for the perspective. Curator: Thank you for yours!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

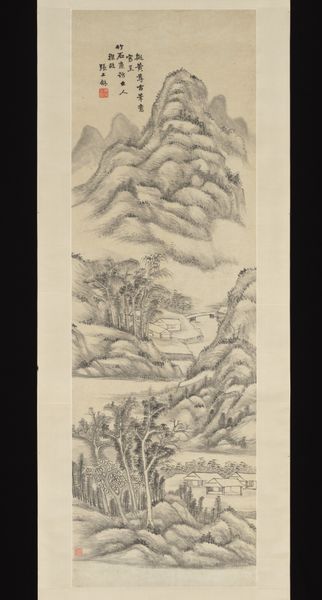

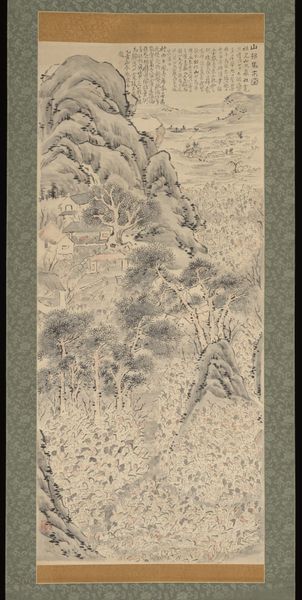

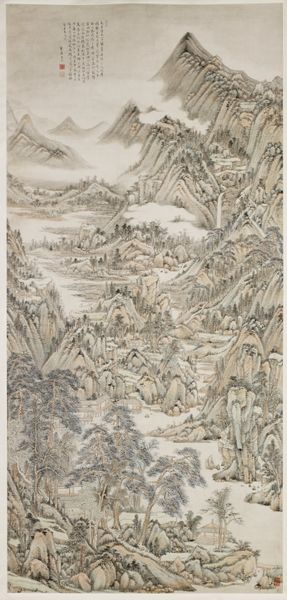

Mighty, gnarled pine trees command the lower half of this enormous landscape, the largest known painting by Gion Nankai, a pioneer of the Nanga movement in Japan. Beneath the trees is a cliffside path with a gate leading to a small hut tucked away in a grove of bamboo. We find the hut’s tenant in a covered boat on the river, being poled by a servant, offering us a viewpoint of and a pathway toward a dramatic landscape of precipitous cliffs, misty valleys, waterfalls, and distant layered peaks. In an inscription at upper right, Nankai describes his work as being based on Solitary Fishing in a Ravine of Flowers, a painting by one of China’s most revered scholar-painters, Wang Meng (1308–85). Nankai also took inspiration from Wang Wei (699–759), the ancient scholar, poet, and painter who was regarded in China, and later in Japan, as the forefather of Nanga.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.