photography

#

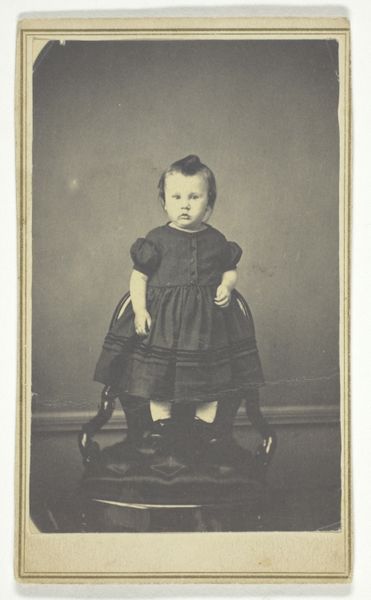

portrait

#

photography

Dimensions: 13.8 x 9.9 cm. (5 7/16 x 3 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a photographic portrait, simply titled “Harry.” The photograph was taken in 1858 by Alfred Capel Cure. Editor: He certainly doesn't look too pleased about it. What strikes me most is the heavy clothing they've put him in – or perhaps her, it's not totally clear. A very ornate dress with large sleeves, coupled with a less than amused expression. There's a narrative already, isn’t there? The gender performance, the infant’s implied rejection of this performance. Curator: Well, dress coded assigned to children didn’t take on such rigid assignments until a few decades later. I suspect its photographic portraiture emerging as an accessible social practice that solidified expectations and hierarchies. The very act of being photographed at this time solidified certain social roles. Editor: Yes, these early photographic portraits served as social performance for the rising middle classes. Curator: And photographic images allowed individuals and families to control their self-representation, as access to new forms of representation transformed identities. Editor: I’m stuck on this idea of performance, or perhaps, *forced* performance. To play devil's advocate here for a second: Maybe little Harry *likes* the frilly dress! Is there agency in a Victorian infant donning of the dress or is this simply another example of historical paternalism and application of present social mores upon people in the past. It all seems very "burden of the past" in its implication, if that makes sense. Curator: Well, considering he would have been a toddler and without many communication skills… but you make a great point. I find these older works so challenging because, on the surface, they seem utterly conventional and traditional. However, as we look deeper, considering elements of social change, performance and gender norms that underpin these images, they take on new layers of meaning. Editor: Precisely, and those layers allow for reinterpretation. It’s these narratives – of resistance, expectation, control, or even happiness – that resonate even after all these years. What do you take away? Curator: For me, it underscores photography’s integral relationship with societal forces and norms that shaped public roles. It is also good to be reminded of the importance of interdisciplinary work that focuses on both historical and intersectional, nuanced issues like identity and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.