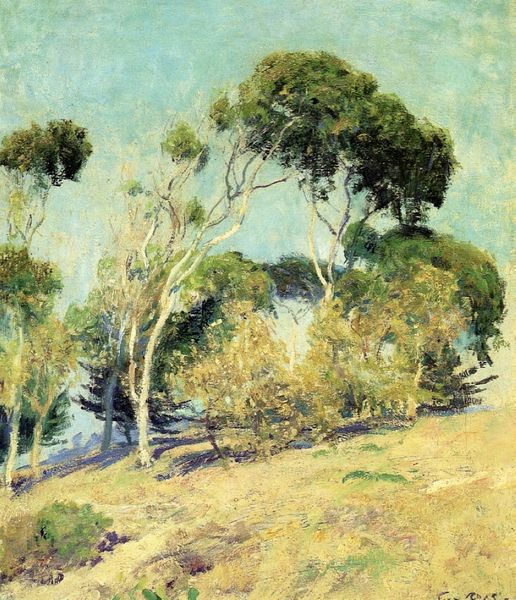

Dimensions: 38.1 x 45.72 cm

Copyright: Public domain

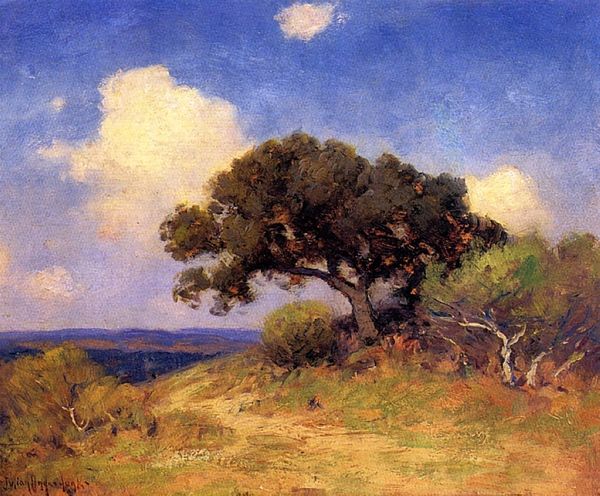

Editor: Here we have Rose O'Neill's "Point Lobos, Oak Tree," painted around 1918. It's an oil painting done *en plein air*, and it gives off this wonderfully serene, almost melancholic vibe. What strikes you about it? How do you interpret this work? Curator: Beyond the surface tranquility, I see a work that subtly engages with notions of landscape and identity. Consider the period: 1918, the tail end of WWI. This scene is almost aggressively pastoral, isn't it? What anxieties might this idyllic image be masking or responding to? Editor: That’s an interesting angle. I was mostly caught up in the brushstrokes, the light...the sheer beauty of the scene. Curator: Beauty certainly isn't apolitical. This landscape seems to resist the rapidly industrializing world and perhaps offers an escape from it, though only for some. The positioning of the oak tree is significant. Consider the tree as a symbol-- historically associated with strength and resilience-- yet, it dominates the picture frame as if obstructing the landscape and potentially the future. What does that tell us about O'Neill's positioning, as a woman artist working in that time, on America’s future? Editor: So, it's less about simply representing nature and more about engaging with larger social issues of the time, filtered through O'Neill's experiences and perspective. Curator: Exactly. Art rarely exists in a vacuum. By considering the context—O'Neill's biography, the historical moment, and the visual language she employs—we gain a richer, more nuanced understanding. This opens a conversation about nature, class, gender, and the unspoken histories embedded within seemingly simple landscape paintings. Editor: I’ll never look at another landscape the same way! There’s so much more to see when we consider these intersectional elements. Curator: Indeed. And that is what makes art so enduringly relevant.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.