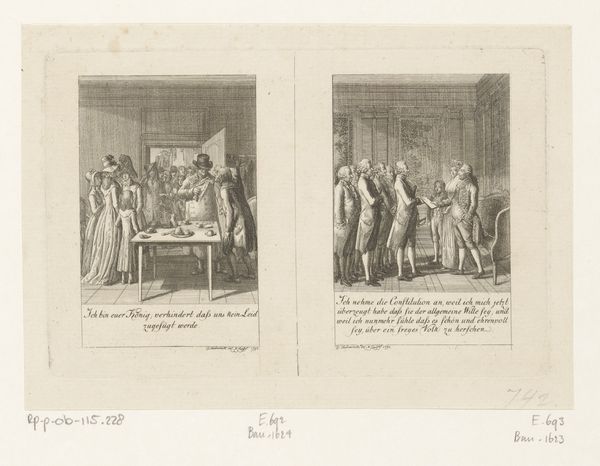

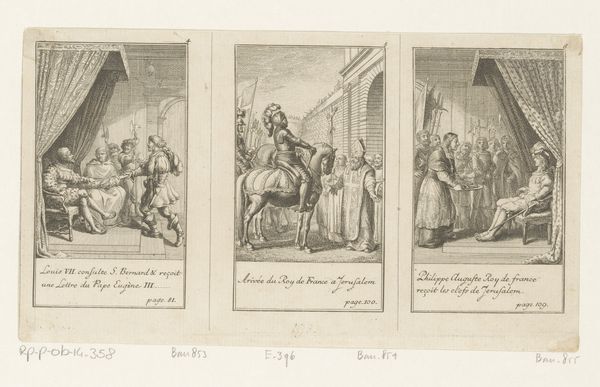

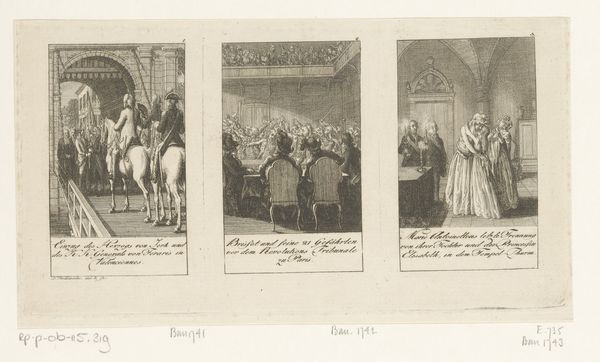

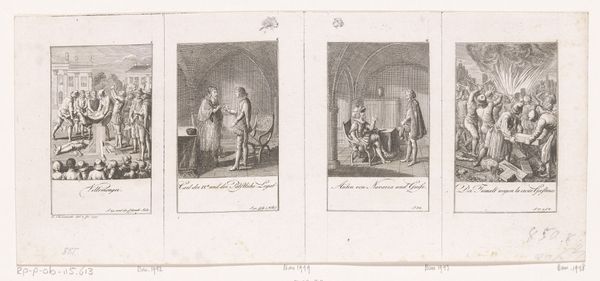

Vier voorstellingen uit de geschiedenis van de Bartholomeusnacht 1799

0:00

0:00

danielnikolauschodowiecki

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

narrative-art

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

romanticism

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 117 mm, width 332 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Vier voorstellingen uit de geschiedenis van de Bartholomeusnacht," or "Four Scenes from the History of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre" by Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki, created in 1799. It's an engraving on aged paper held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression? Stark. A series of small windows into violence, rendered in delicate lines, but ultimately chilling. The effect of the aged paper only intensifies that feeling. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the context: this piece was created over two centuries after the actual events of 1572. Chodowiecki, working in the late 18th century, is engaging with a very specific historical memory. These aren't just scenes of violence; they're reflections on religious conflict and political instability. Editor: I'm interested in the printmaking itself. The fine lines of the engraving – what kind of labour went into creating something that almost mimics the effect of a quickly drawn sketch? And how does this reproductive method allow for broader consumption and distribution of this violent historical narrative? It challenges the preciousness associated with singular art objects, doesn’t it? Curator: Precisely. The reproducibility of engravings meant that these images could circulate widely, influencing public perception of the past. Furthermore, it invites consideration of who controlled the narrative surrounding the massacre and to what purpose this history served for audiences in the 1790s. Editor: It strikes me as almost… pedagogical. Each scene feels carefully chosen to convey a specific point in the sequence of events, much like the illustrations in history books intended for educational consumption by a literate public. Curator: I think that's a keen observation. And beyond the immediate horror, we should recognize this as a commercial print intended to shape its consumers' notions of history, the power of the printing press and how these objects enter homes as historical or decorative prints. Editor: So, far from a passive observer, Chodowiecki seems to be actively constructing an interpretation of this historical trauma, one meant for mass consumption, even for profit. It begs us to contemplate the role art plays in shaping collective memory. Curator: Indeed. The power of images like these to frame our understanding of historical events is profound and should be further examined, revealing how museums should work hard to challenge simple narratives. Editor: Food for thought. I’ll certainly not see an unassuming engraving as purely representational again.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.