print, photography

#

aged paper

#

homemade paper

#

paper non-digital material

#

paperlike

# print

#

landscape

#

personal journal design

#

paper texture

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

folded paper

#

publication mockup

#

letter paper

#

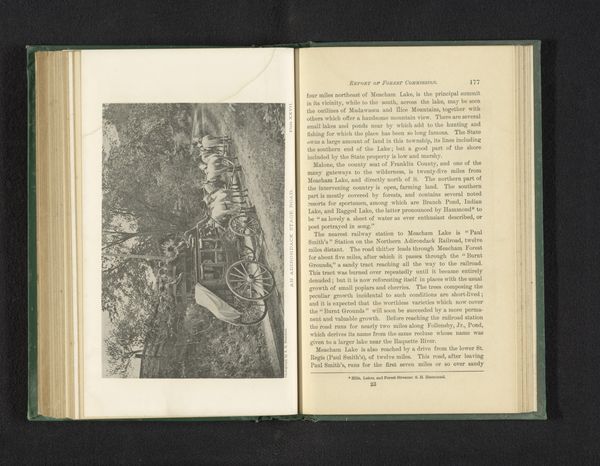

naturalism

Dimensions: height 110 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: My initial reaction is… melancholy. The faded sepia tones and grainy texture give it a wistful air, like looking at a memory. Editor: This is "Adirondack Game," a print from 1894. The artist is G.H. Rison. It appears to be a photograph reproduced in a book. It’s interesting to consider this work as an artifact of its time, a moment when industrialization was rapidly transforming the landscape. Curator: Right, I was drawn in by how much depth the image creates despite being small and existing within the aged, slightly yellowed pages. The contrast pulls the hunter forward, while the surrounding foliage blends into an impenetrable darkness, it makes you feel swallowed by the immensity of nature. Editor: Yes, and the title "Adirondack Game" is charged. Think about the ethics of hunting and how that intersects with class. Who has the privilege to engage with nature in this way, framing it as a 'game'? The hunter's posture, bending low with a rifle, it embodies that dynamic. The photograph and book are tools that were used at the turn of the century to project both leisure and the exploitation of nature. Curator: Hmmm, perhaps it hints at something else too – our own vulnerabilities. We play games with nature, but nature will ultimately have the last laugh, won't it? Editor: Definitely. The act of publishing, the act of distributing this image is about shaping a particular narrative. A narrative where man dominates nature. Where we frame naturalism and hunting, as separate— and at the advantage of humans. But look at that density, the tangled undergrowth… nature resists those narratives, doesn’t it? Curator: Precisely. This image serves as a reminder that there's an ongoing interplay between dominance and the wild. Something beautiful and troubling, forever shifting. Editor: It also speaks to a past when conservation efforts weren’t as urgent or well-defined as they are today. “Adirondack Game,” through its photographic lens and through its positioning on the pages of this book becomes part of a story of natural exploitation during the 19th century. Curator: So, this faded image really stirs up questions, not just about then, but about our own place in the natural order today. Maybe its melancholy lies in that recognition. Editor: Absolutely. Looking closely helps us rethink dominant cultural frameworks and re-contextualize their role in shaping perceptions and practices surrounding the exploitation of nature and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.