oil-paint

#

baroque

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

jesus-christ

#

christianity

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

christ

Copyright: Public domain

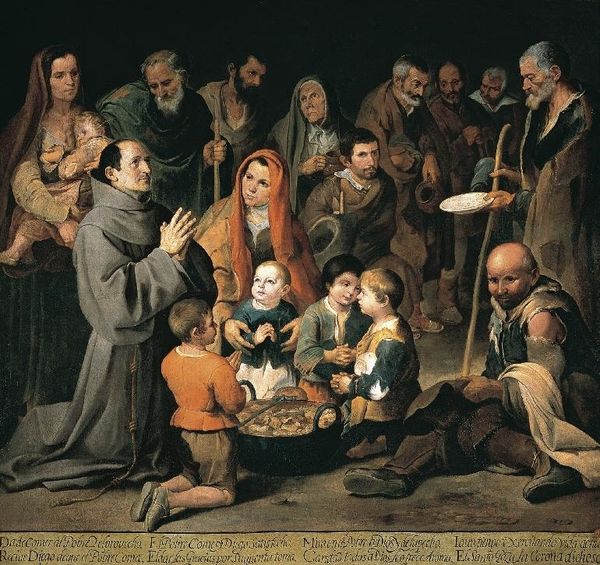

Curator: Alright, let's dive into Gabriel Metsu's "Woman Taken in Adultery," painted around 1653. It’s an oil on canvas, and a powerful take on the New Testament story. Editor: Wow, right away I'm struck by the heavy contrast, the way darkness kind of devours the edges and makes the central figures almost glow. It's incredibly dramatic, in that signature Baroque style. Curator: Precisely! Metsu really captures the theatricality inherent in Baroque painting. You see Jesus down there in a humble pose in pink, and then, that central figure—the woman. Editor: She’s really the focal point, isn’t she? The expressions of shame and supplication are very striking, enhanced by the positioning, the architectural layout with dark ominous structures. The whole narrative feels charged with social tension. It kind of begs questions, right? Who are we to judge? What does justice even look like in these deeply patriarchal power structures? Curator: Absolutely. It pulls you right into the moral complexities of the scene. And those figures flanking her, the scribes and Pharisees, seem to embody institutional judgment, holding their books, a contrast between divine forgiveness and societal condemnation. It almost feels like he's winking to those of us who know our scriptures—he certainly isn't buying the sincerity of that crowd. Editor: Exactly. They're almost cartoonishly severe! In this historical context, it is worth thinking about gendered aspects to moral law, and how quickly these forms of 'justice' were mobilized in the oppression of women. This scene, I feel, presents an interesting tension between divine intervention and ingrained misogyny. Curator: Yeah, it's interesting. In a way, I see Christ’s position as speaking back into the structures which dictate punishment onto that woman. Perhaps his is a divine intervention. Editor: I agree. I find it amazing that nearly four centuries later, we’re still grappling with these same issues of judgement, forgiveness, and the societal pressures placed particularly on women. The artist’s perspective, while rooted in his time, still prompts such timely questions, in the context of current societal issues, whether you consider contemporary cultural discourses, historical precedents, or even law and policy, to ask ourselves about those holding the power, and the impacts on those facing punishment, as this woman is in the work. Curator: So well said! And, you know, stepping back, that's exactly what makes art from centuries past so resonant, isn't it? These eternal questions wrapped up in gorgeous pigments and brushstrokes, reflecting then, and informing now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.