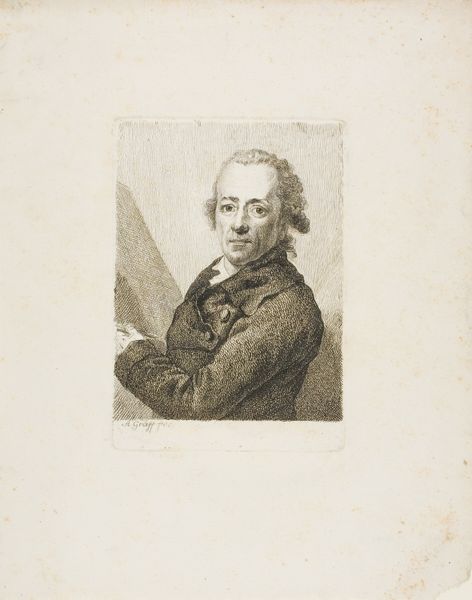

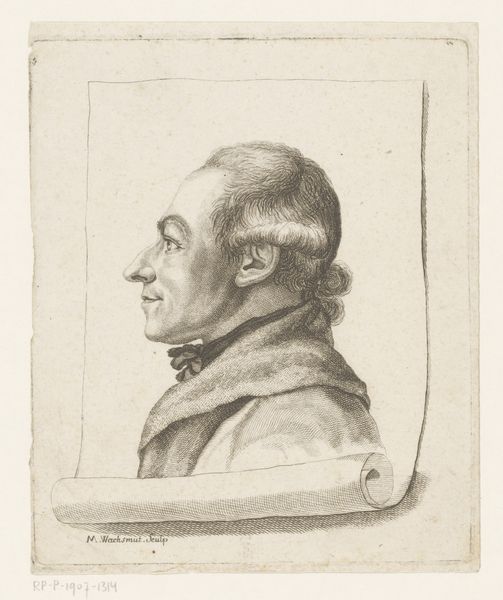

Dimensions: 100 mm (height) x 75 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This engraving, rendered in 1788 by Gerhard Ludvig Lahde, is a portrait of the painter Anton Graff. The fine lines create a surprisingly intimate, albeit formal, depiction. Editor: Intimate is a great word, even though it also feels distant. His eyes seem to hold a profound pensiveness, a subtle world-weariness. Is it the lighting or something more ingrained, some melancholy of the era perhaps? Curator: Melancholy certainly permeated the late 18th century, marking a shift away from the grandiose Rococo into a more introspective Neoclassicism, politically and artistically. Prints like this were crucial, not just as portraiture, but as a form of visual communication. How else would artists share their work and reputations? Editor: Exactly. And looking at this engraving, one is immediately struck by how social standing shapes artistry. Graff is presented with an assuredness, the engraver emphasizes refined garments and styled hair; but can you see how the rendering can be said as also suggesting certain inequalities and a reliance on privilege? Curator: The art world was inextricably linked to power and patronage. The print medium afforded a wider circulation and influence. Graff, a celebrated portraitist in his own right, understood the power of self-fashioning through such representations. Engravings could elevate his public image, fostering professional networks. Editor: Beyond the societal implications, I'm drawn to Lahde's rendering style. The crosshatching creates dimension in what could otherwise be flat. It humanizes Graff; despite any formal conventions that existed, Lahde successfully presents flesh and blood rather than a detached emblem of status. I feel sympathy for this face. Curator: Lahde, while lesser known today than his sitter, certainly demonstrates impressive skill in the art of engraving here. That sensitive balance between formal presentation and personal character you mention is one key to the print’s enduring appeal. His craft deserves consideration in itself. Editor: Ultimately, “Portrait of the Painter A. Graff” gives a voice to discussions about who holds authority and what kinds of statements get amplified in historical contexts. It goes beyond being just a representation. Curator: Absolutely. By exploring the social fabric embedded in such artworks, we enrich our understanding of the past. Thank you for sharing this perspective, as usual!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.