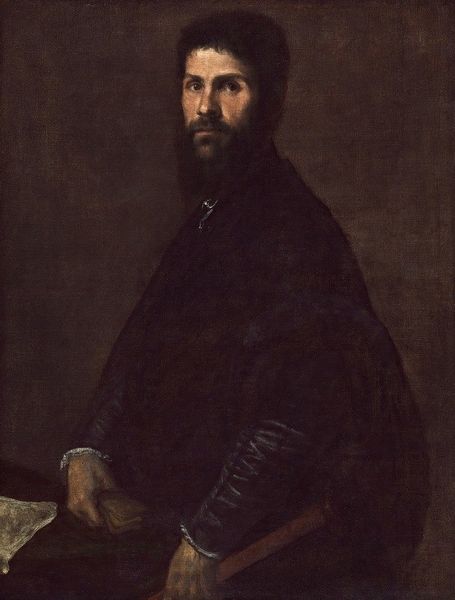

oil-paint, canvas

#

character portrait

#

oil-paint

#

mannerism

#

canvas

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 108 cm (height) x 84 cm (width) (Netto)

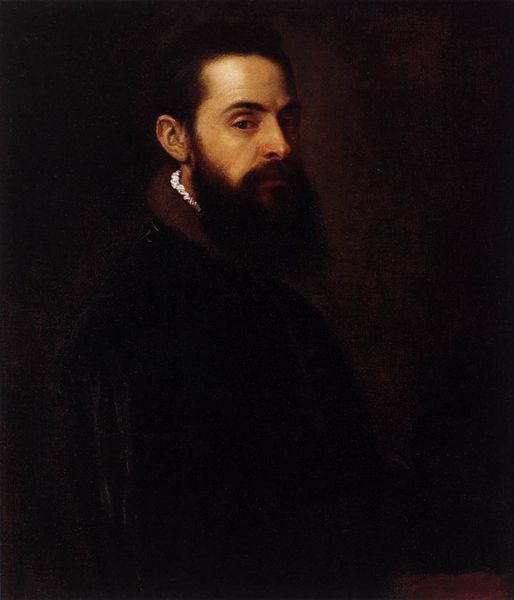

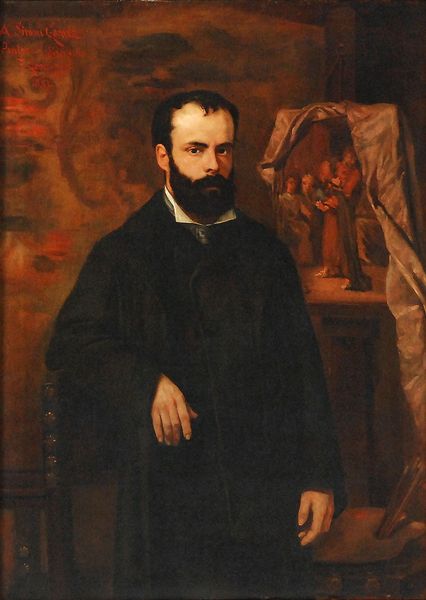

Curator: Here we have Federico Barocci’s "Portrait of Antonio Galli," created sometime between 1550 and 1612. Its oil on canvas, currently held here at the SMK. Editor: The initial impact is of something quite somber. A prevailing darkness. It feels heavy somehow, doesn't it? Like it’s absorbing the light. Curator: Indeed. Note how Barocci orchestrates this effect through the chiaroscuro. Observe the geometry of the figure—a stable triangular form bisected by subtle lines of light and shadow. Editor: Yes, the shadow does more than create form; it's material in itself. I find myself wondering about the pigment itself—the depth of the black and how that affected the canvas itself. Was this figure somber or made to look so by the dark medium, given his placement amidst tools of calculation or the fine details on the little clockwork object there? Curator: Consider this: his hand, positioned deliberately over a closed book, with what we understand to be a small mechanical clock alongside, might it signify a subtle critique of scientific inquiry? The gesture itself is one of restrained intellect, not raw labor. It certainly presents the subject as contemplative and intellectual rather than a figure of physical production. Editor: Contemplative perhaps, but even intellect is a material process tied to lived conditions. Who was Galli? The objects tell me the artisan and perhaps he used new techniques or material, pushing what was possible. He is not merely sitting and thinking for leisure; he produces and tinkers to give utility or time to a patron. Even as it shows how that labor translates to elevated societal status, it represents what the raw products become when transformed by such work. Curator: I take your point on context. Yet the artwork speaks to an established aesthetic of the Mannerist period, a tension, as we observe in the contrapposto evident in his seated pose. He seems simultaneously at ease and subtly uneasy, which in turns speaks volumes. Editor: Perhaps our division of labor and material is merely of degrees. I’m left thinking about how we might restore some tactility and recognition of work back into our discussions about the arts. Curator: Food for thought, certainly as one leaves the hall.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.