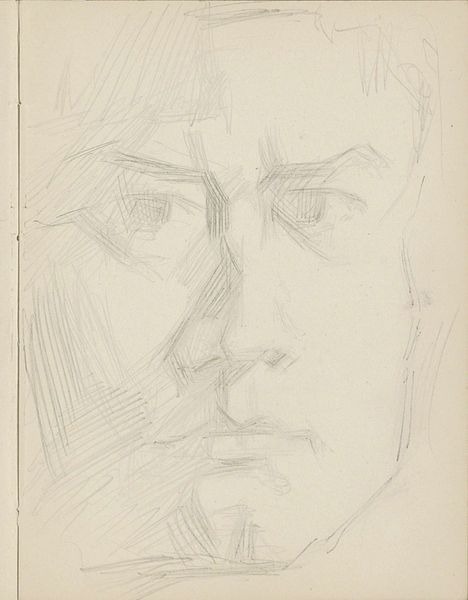

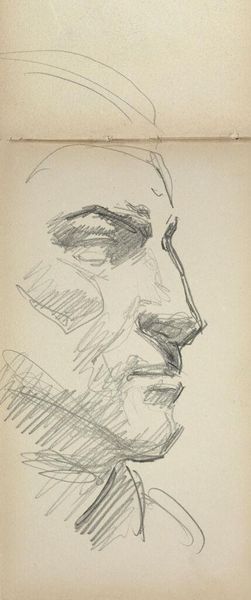

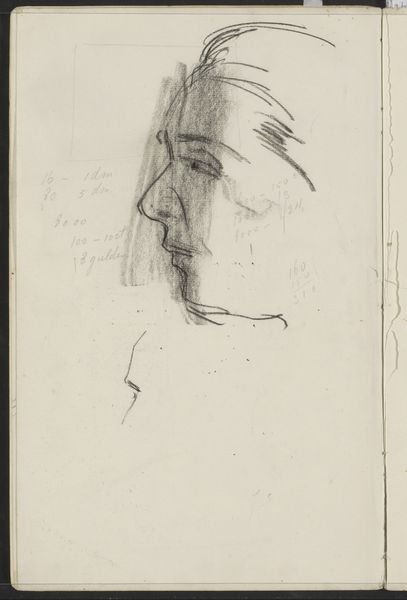

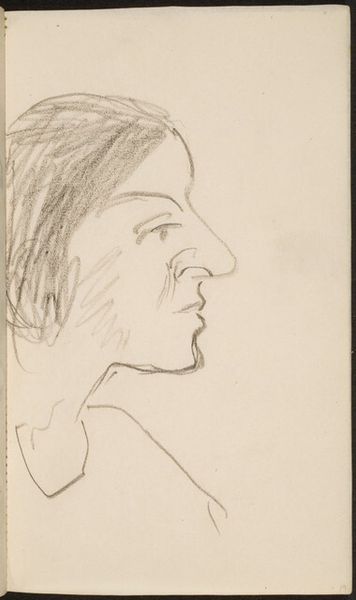

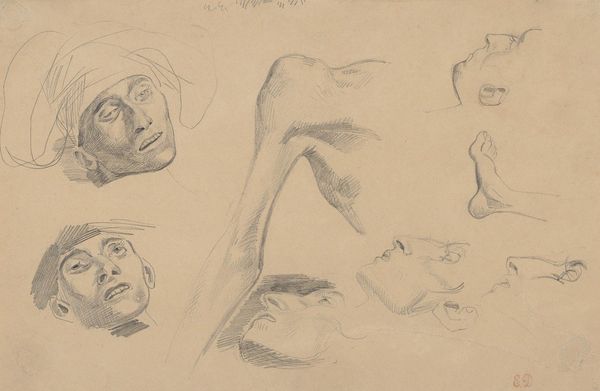

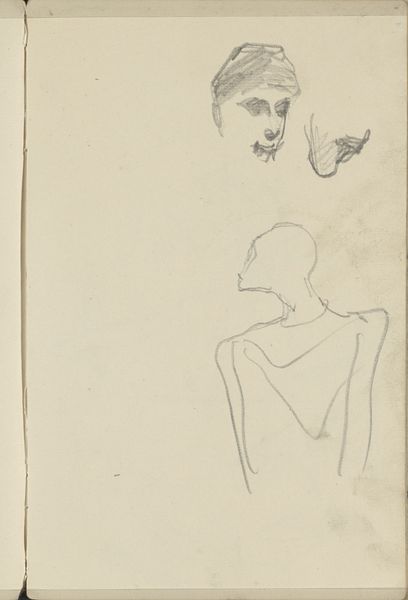

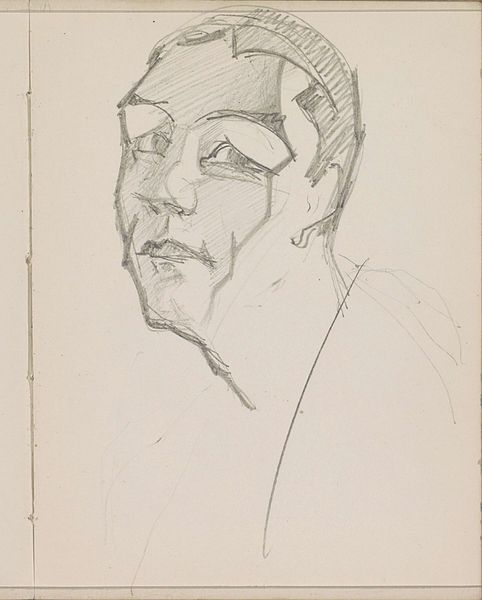

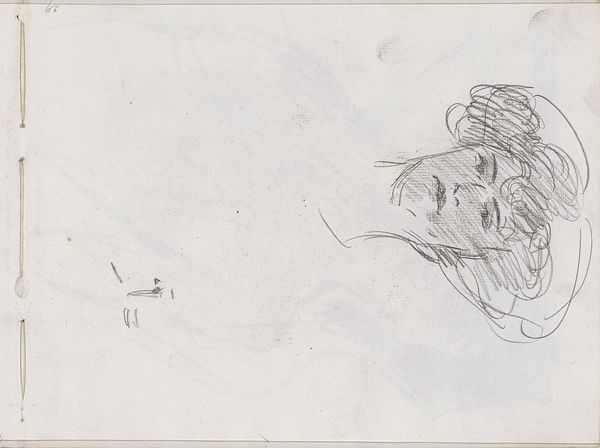

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

face

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

realism

#

initial sketch

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

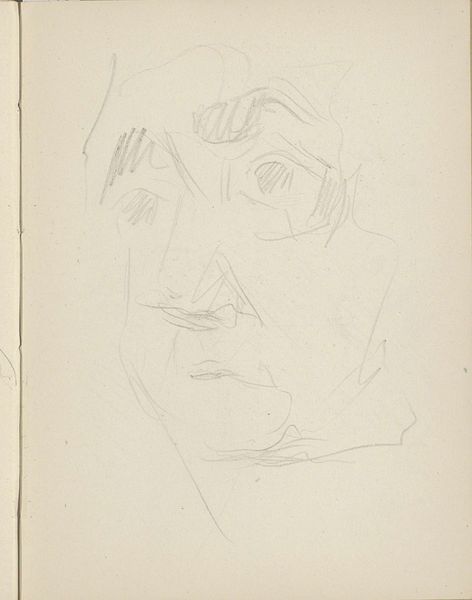

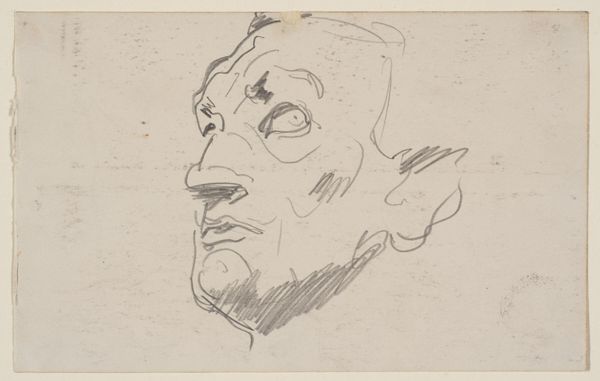

Curator: Breitner's "Gezicht," dating from 1887-1889, presents us with an intimate glimpse into the artist's sketchbook, housed now in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the economy of line, the sheer scarcity of means. It feels like an echo, a ghost of a face conjured with minimal material effort. Curator: Absolutely. And considering the social circles Breitner occupied, who might this be? Is it a fleeting muse, perhaps a working-class woman encountered in the streets of Amsterdam, captured in a moment between her labor and her private life? Editor: Or perhaps simply someone who caught his eye on the tram! What’s fascinating for me is that we have a basic implement--pencil--performing the preliminary labor. I see this almost as a raw material itself, waiting to be fully realized in another medium. Curator: But it is, undeniably, art in its own right. Note the delicate hatching that suggests volume and depth, particularly around the eye sockets and cheekbone. Breitner, a chronicler of modern life, isn't just sketching a face, he is hinting at psychological depth. Do we see resignation, weariness, or something more complex? Editor: That’s where I hesitate. The unfinished quality foregrounds the act of making, it disrupts any clean narrative about the subject’s psychology. The medium itself, a humble pencil, its ready availability...it democraticizes art, making a study like this possible, quick, cheap. Curator: Yet the selective rendering complicates any purely democratic interpretation. While seemingly spontaneous, the precision with which he defines certain features – the set of the mouth, the downward cast of the eyes – suggests an intent beyond mere observation. The subject’s class identity, for instance, isn't just incidental; it's consciously marked. Editor: It all goes to show that pencil marks are never simply neutral. Look how it fades away near the hairline as if suggesting absence. Curator: Indeed. By understanding this sketch within Breitner’s larger oeuvre and the broader context of late 19th-century Amsterdam, we gain a rich understanding of how the personal and the political intersect. Editor: Yes, it reminds me that behind every finished portrait, behind every monumental artwork, are countless hours of often invisible, underappreciated material experimentation and labor. Curator: A truly fascinating glimpse into an artist's process, viewed from such different, yet intertwined perspectives!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.