drawing, painting, watercolor, pen

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

painting

#

figuration

#

watercolor

#

pen

#

history-painting

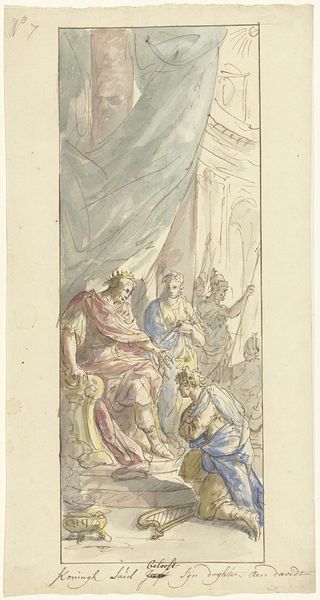

Dimensions: height 314 mm, width 204 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: The scene has a tentative grace despite depicting a rather dramatic moment. It's quite spare, yet suggests grand architecture. Editor: This is "Esther before Ahasuerus," attributed to Gerard Sanders and likely created sometime between 1712 and 1767. What we’re seeing is rendered using pen, watercolor, and drawing techniques on paper. It's a Baroque piece representing a key moment from the Book of Esther. Curator: Right, Esther bravely approaching the king… There’s such vulnerability in those kneeling figures and it's so effectively contrasted with the stark formality of the king and his throne. I’m struck by the physical act of kneeling, and how even a queen would still have to lower herself in his presence. This image communicates that dynamic so strongly. What did the materials making the image communicate to contemporary society? Editor: I agree. The staging of power is paramount, and you can see the institutions literally built around that dynamic: that classical archway looking out onto manicured gardens, the rigid architecture within which the king's power is made visible and secure. The availability of watercolors and pen meant narrative scenes like this became increasingly accessible beyond just the aristocratic circles; printed versions of similar scenes made these stories accessible and malleable. Curator: Absolutely, there’s something almost ephemeral about the washes of watercolor that makes it feel quick, readily reproducible. Was that intentional or simply an expedient artistic decision for Sanders? The paper becomes another element in how the message reaches the public. Editor: That’s hard to say for sure with Sanders specifically. However, thinking about paper production in the early 18th century, one notes a link between Dutch trade networks and paper production – both crucial components of this piece. What also gets my attention are all the social structures involved: royal patronage, artistic training, and then the market for these images, and what biblical scenes specifically communicated to the public. Curator: These scenes, mass-produced through printmaking, would have become important vehicles for shaping moral, political, and religious values within Dutch society and beyond, wouldn’t they? And even in painted pieces they are influencing perception and values in society by highlighting the moral issues of the stories. Editor: Precisely, and the Baroque style emphasizes dramatic tension and emotional engagement, enhancing that impact further. What a layered set of power structures this work depicts and embodies. Curator: Exactly. It truly shows how access to a biblical story through print has transformed its role from simply a sacred religious moment, but something now directly engaged in the construction of society’s values and social commentary. Editor: Indeed. I come away from this piece considering the ongoing, shifting relationship between art, power, and the narratives that define a people.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.