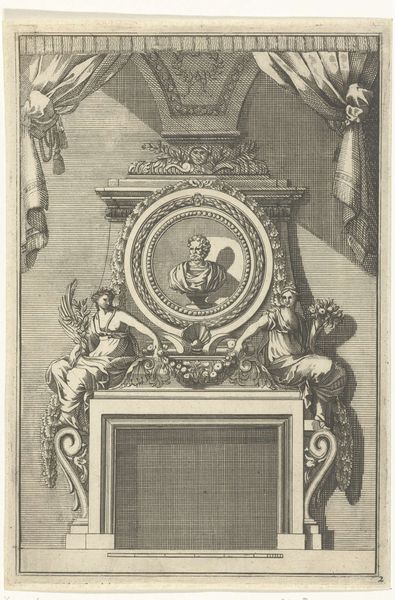

Dimensions: height 252 mm, width 168 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this piece, I’m immediately drawn to the rigid, almost architectural framing around what seems like a serene portrait. What’s your initial impression? Editor: The detail in the printwork is astounding, especially given its apparent age. The stoic, detached presentation feels incredibly controlled—reflecting perhaps, a very specific agenda of power. Curator: Indeed. This is a print of Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, created by Johann Esaias Nilson sometime between 1765 and 1788. As an engraving, its production would have been highly skilled, involving carefully etching lines onto a metal plate. Notice the almost industrial precision—uniformity was key for distributing these widely. Editor: And that distribution speaks volumes. These portraits, reproduced en masse, are carefully constructed tools used to build an imperial brand. How does it influence societal understanding, the subjects of the empire’s view of their leader and subsequently, their assigned place within this structure? It's a fascinating intersection of art, power, and early mass media. Curator: Absolutely, the Neoclassical and Baroque influences combine in interesting ways here. We have the grandeur associated with power – visible in the ornate cartouche, but rendered using the linear, controlled aesthetic that began defining the era. It speaks of manufactured consent, using art for projecting a particular image. Editor: I agree. Consider the social implications, the very *process* of creating this idealized representation versus the material conditions for ordinary citizens during Joseph II's reign. Does this romanticized profile serve to justify the unequal distribution of power and wealth? What narratives are deliberately being reinforced here and which ones were actively silenced by controlling production? Curator: An important point. And reflecting on materiality: the relatively cheap, easily disseminated prints reached a far broader audience than unique painted portraits. So, while seemingly rarefied, these kinds of images served an important function in promoting ideology. Editor: It pushes us to question art’s role in history, and it requires deep thinking about those intersections of politics, art production, and power dynamics. Curator: Definitely a powerful snapshot, urging us to look critically at the materials of history and those who controlled their creation. Editor: Indeed, something seemingly decorative actually encourages a broader understanding about image creation and distribution and what effects those processes can achieve on society.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.