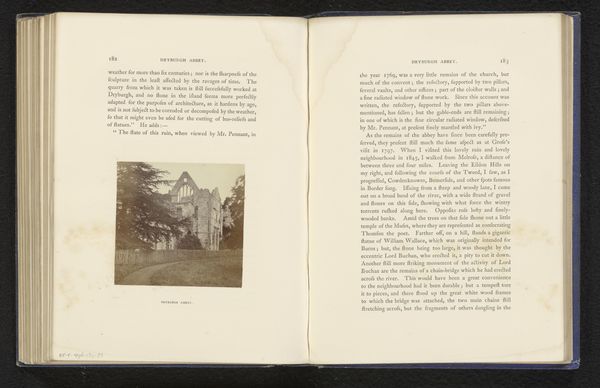

print, photography

#

medieval

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

Dimensions: height 73 mm, width 86 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Gezicht op de Llanthony Priory," a photograph by Francis Bedford, dating from before 1862. It appears to be a page from a bound book. Editor: It has a melancholic atmosphere, doesn't it? The delicate sepia tones lend it a ghostly quality. And look at the architectural skeleton framed so centrally; it directs your eye through the archways straight into an ambiguous vanishing point. Curator: It's quite common, really. During this period, the burgeoning field of photography was significantly intertwined with Romanticism and historical preservation. Bedford’s works, like many of his contemporaries, served to document and, arguably, idealize these medieval ruins. Editor: Idealize? How so? The contrast feels quite stark – the stark outline against a bleak backdrop does feel so hopeless. There seems no life, only time consuming itself in the destruction. Curator: Consider the socio-political context. Llanthony Priory, like many monastic sites in Britain, was dissolved under Henry VIII. For Victorian society, these ruins became potent symbols of a lost, supposedly more spiritually devout, past—one that the Church of England sought to evoke as part of its own self-fashioning. Editor: Yes, the aesthetic construction of nostalgia. But the formalism remains fascinating; note how the stark horizontality of the composition—the fallen walls—contrasts with the implied verticality of the intact abbey that we are to imagine… Curator: And imagine the viewers would! These images functioned to establish continuity between the medieval past and the Victorian present, lending weight and legitimacy to the dominant social order of the time. They subtly asserted cultural dominance and historical narrative through circulation in various books and print media. Editor: Quite. So, while my eye is drawn to the contrast and tonal shifts of this faded print, you point out that such scenes carry broader implications tied to power, memory, and identity? It gives me much food for thought. Curator: Exactly. It highlights how art never truly exists in a vacuum—but rather in conversation with broader historical forces.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.