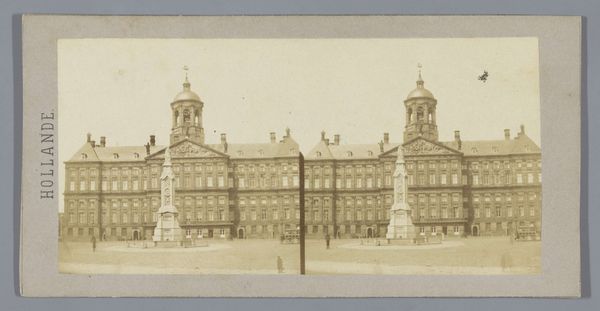

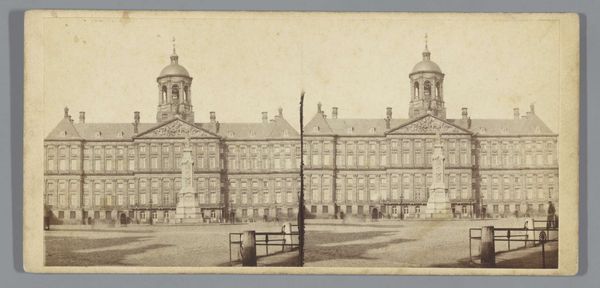

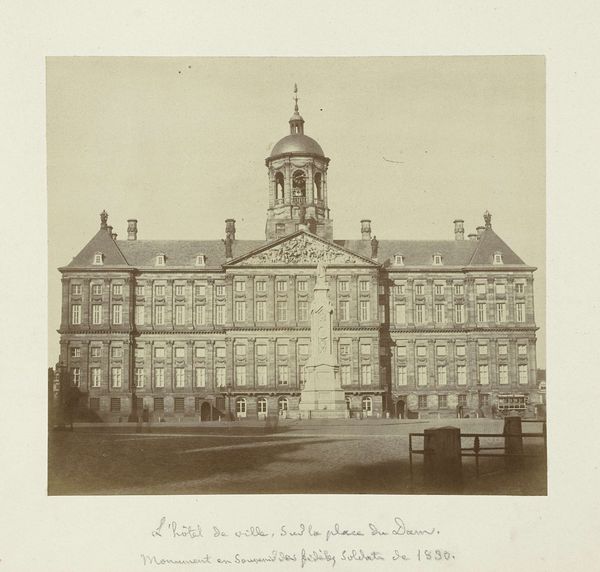

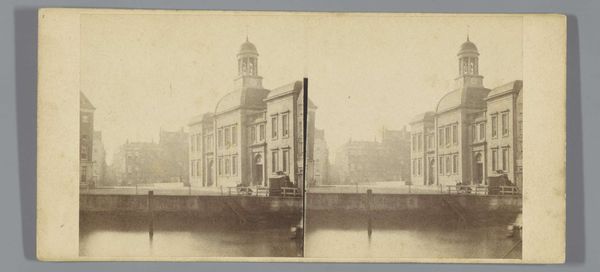

Koninklijk Paleis op de Dam en het Monument ter herinnering aan de Volksgeest van 1830 en 1831, genoemd Naatje, Amsterdam before 1859

0:00

0:00

pieteroosterhuis

Rijksmuseum

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 173 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

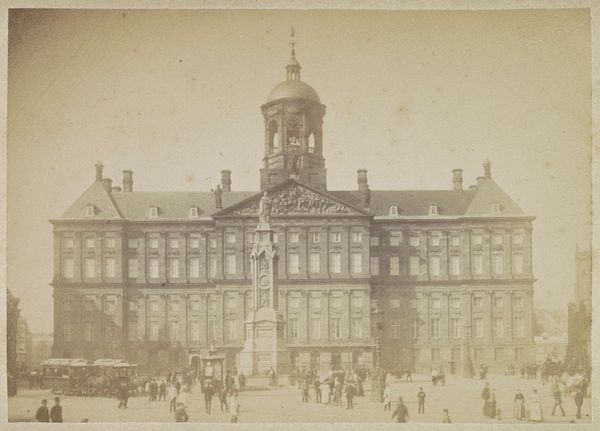

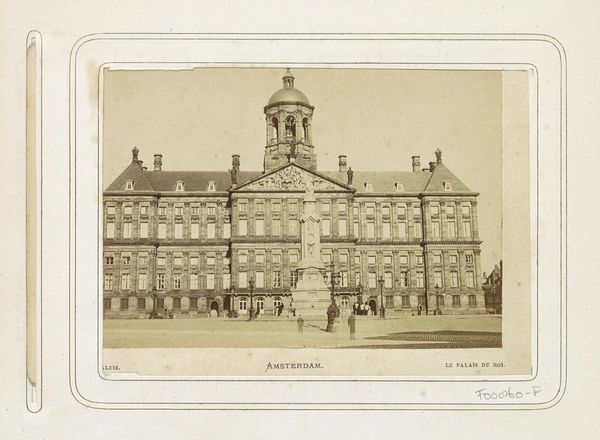

Editor: This is a photograph taken by Pieter Oosterhuis before 1859, titled "Koninklijk Paleis op de Dam en het Monument ter herinnering aan de Volksgeest van 1830 en 1831, genoemd Naatje, Amsterdam", a gelatin-silver print. The scene has a very still quality to it. I'm drawn to the clear geometric layout of the Palace, with the monument in the foreground, seemingly captured at eye level. What strikes you about its composition? Curator: Indeed. Note the carefully constructed symmetry: the building, with its repeating windows and defined stories, creates a grid-like structure. Observe also how the placement of the monument creates a vertical counterpoint to the horizontal spread of the palace. Consider how this strict geometric layout gives rise to the perception of stability and order, an idea of power and authority, don't you think? Editor: Yes, I agree. But the choice to duplicate the view – what effect does that have? It almost flattens the image, making the perspective feel slightly off. Curator: Precisely. This near-replication, technically a stereoscopic print, aimed to create a three-dimensional effect when viewed through a stereoscope, a popular optical device during the 19th century. Its impact stems not merely from depicting reality but from actively shaping its visual representation. It engages in a play of presence and absence. The photograph documents, yet simultaneously manipulates spatial perception. We observe the inherent paradox of representation—its dependence on artifice and subjective interpretation. Editor: That makes the architectural precision all the more poignant. I guess it is an example of Neoclassicism too? Curator: Without doubt. The architectural vocabulary —columns, pediments, a dome— evokes the grand structures of classical antiquity, reinterpreted in the 19th century to symbolize civic virtue and imperial authority. Neoclassicism aimed for universal and rational ideals, using form as its primary mode of communication. Editor: Thanks. Looking at it that way makes me reconsider the nature of photography and architectural form in one swift move! Curator: I think focusing on the structure of Oosterhuis’ composition allows for that precise form of intellectual engagement, as structure necessarily predicates purpose, even when unintentional.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.