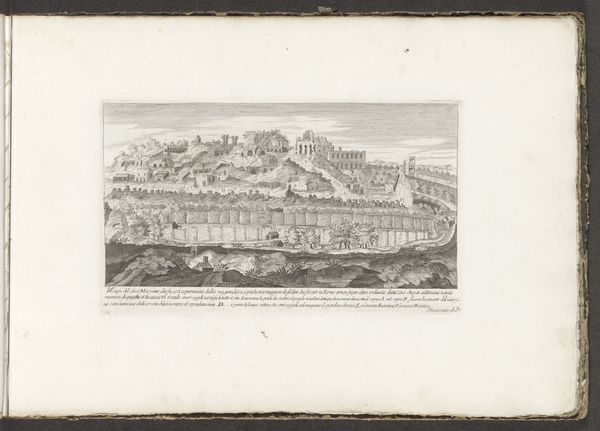

drawing, ink, engraving

#

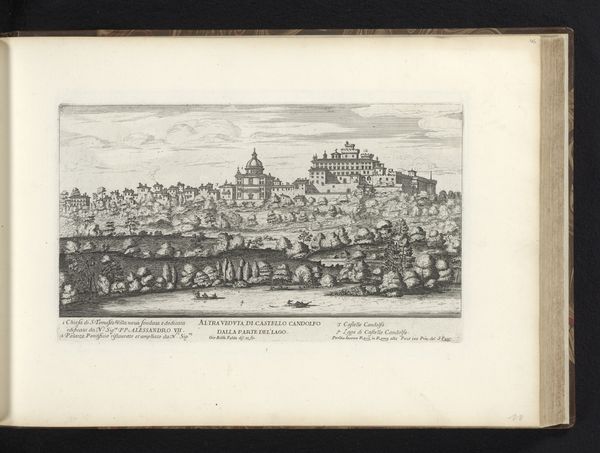

drawing

#

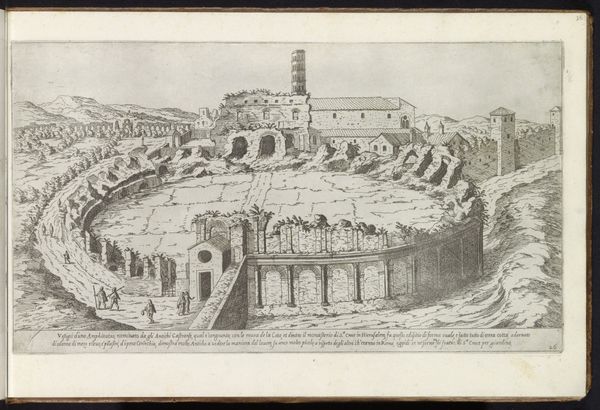

pen drawing

#

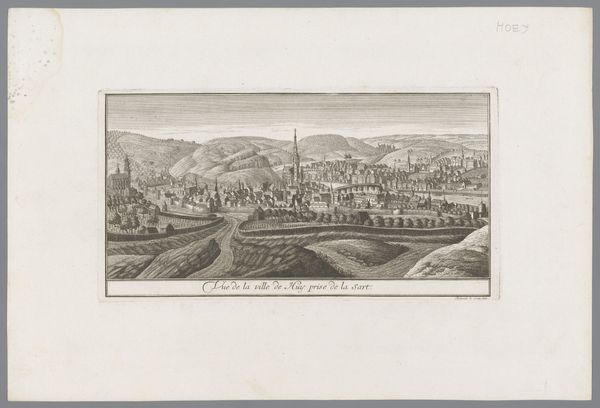

landscape

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

engraving

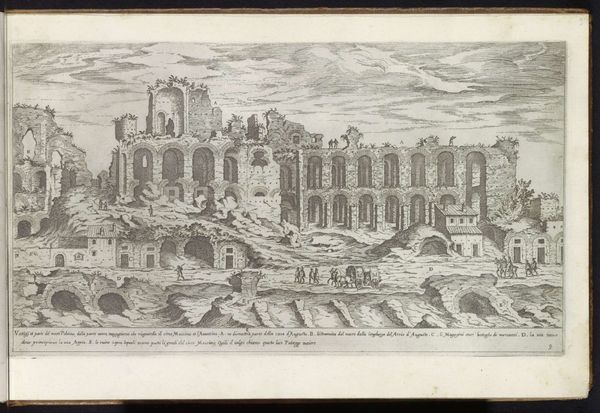

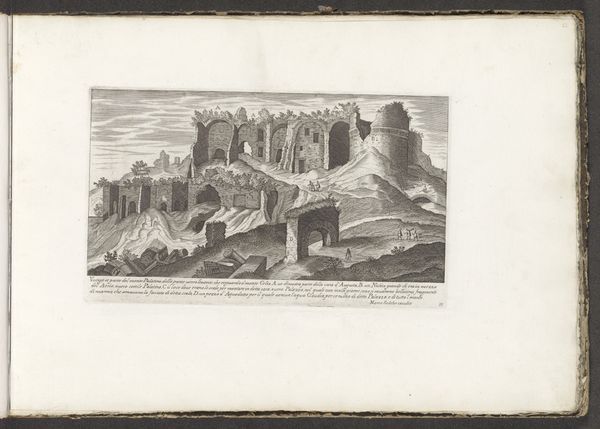

Dimensions: height 214 mm, width 385 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

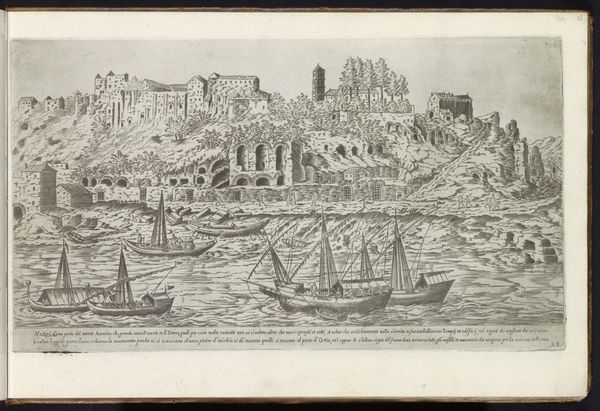

Curator: So here we have Étienne Dupérac's 1575 engraving, "Palatine Hill and the Circus Maximus in Rome," held here at the Rijksmuseum. What's catching your eye? Editor: It's... melancholy. Ruins always get to me. So much history rendered into a delicate, slightly chaotic web of lines. It makes me wonder about the original stonemasons, the lives lived and lost within those walls. Curator: Precisely! Dupérac wasn't just rendering a pretty picture; he was documenting the physical state of Rome. Look at the stark detail in the etching—the crumbled architecture atop the Palatine Hill contrasting with the relatively intact Circus Maximus. Editor: And that precision is incredible. It reminds me that engravings were a crucial technology for disseminating knowledge, especially architectural plans and cityscapes. This print could be instrumental to understanding 16th-century Rome, both physically and how its image was circulated. Was Dupérac consciously considering labor as he documented its urban space and ruin? Curator: Perhaps he was less focused on the laborers than on the grand sweep of history, the rise and fall of empires represented by these stones. Notice the vantage point, slightly elevated, almost as if we’re hovering over the scene. The drawing style certainly leans into an imagined sublime rather than being focused on specific peoples. Editor: Still, every deliberate line represents a choice in labor - an intentional process of revealing certain narratives while obscuring others. Look at the uniformity of lines he uses to represent similar architectural blocks in contrast to the broken shapes around them. Curator: True, it all contributes to this sense of bygone grandeur. The way the light and shadow play across the Colosseum or the implied crowds… he wanted to evoke a feeling, maybe of loss, of reverence. Editor: Or of empire. And maybe Dupérac saw his own role in etching the plates as parallel to the laborers he wasn't explicitly documenting. The matrix and plate are like a mold for an empire's image, a commodity sold at scale. Curator: That's a fascinating parallel. Considering it this way, the act of reproducing and selling the artwork itself as an empire building venture. It transforms our sense of looking at it here and now, centuries later. Editor: It does change things. It gives one something to chew on when simply staring, I appreciate the way we looked at an apparently simple picture from the past. Curator: Me too, such a view that really makes one dream of wandering.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.