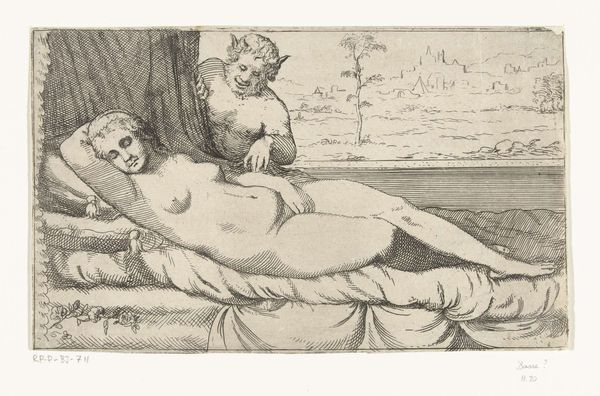

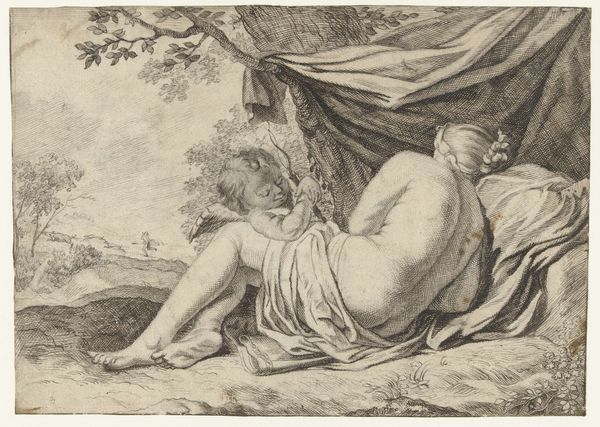

etching

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

etching

#

portrait reference

#

portrait drawing

#

nude

#

realism

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 69 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Look at this etching by Wenceslaus Hollar, titled "Naakte vrouw, gezeten op een verhoging," from 1635. It's currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's a kind of vulnerable stillness in this image that arrests me; the almost-imperceptible hatching gives her flesh a delicate glow. Curator: Hollar, Bohemian-born but active in England, was quite prolific as a printmaker, known for his detailed cityscapes and portraits. He certainly shows us the reality of a body. Editor: Indeed, far removed from the idealised female forms that were usually circulated in prints. Considering that this piece is entitled 'Naked Woman, seated on a rise' perhaps the "rise" or social platform granted to this depiction normalizes—elevates, even—everyday female representation? This etching's creation speaks volumes about societal interest in depictions of normal human forms, or perhaps even new methods for sharing it due to access. The lines have so much variance. You can imagine the biting of the acid to realize those deeper, thicker ones. Curator: Exactly. Etching allowed for a freedom of line that engraving didn't offer, fitting in a period when printmakers began to value this aspect. Editor: Let's not gloss over the sheer amount of labor. Etching wasn’t as physically demanding as engraving but requires a thorough working knowledge of grounds and acids, careful timing, and immense patience. Then you’d have the process of proofing to correct any faults. It shows how knowledge of the tools makes production a tangible process. How the maker’s hand guides how this comes into our presence. What do you think, knowing the artistic, laborious methods for its time? Curator: It’s hard not to be struck by the contrast between her placid expression and the incredibly sharp details around her. She looks surprisingly self-possessed, unflinching to whoever views. She's taking up space and wants to be seen in that act, or be represented somehow. I also love this lack of any embellishment; the directness in both subject matter and technique is compelling. Editor: You know, looking at this closely, it makes me realize that it's an intimate piece but with complex origins when it comes to how art history represents certain individuals and demographics throughout art movements and artistic value. This all began due to processes accessible at the time... and yet we are still debating their significance today. Curator: True, but through Hollar's eyes, we are granted the permission to linger—to observe not just art, but a reflection of life itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.