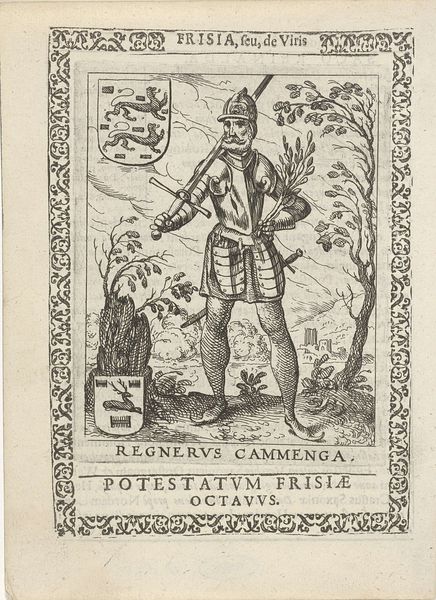

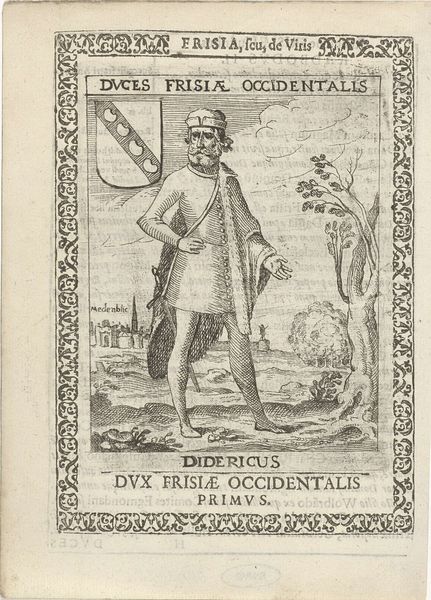

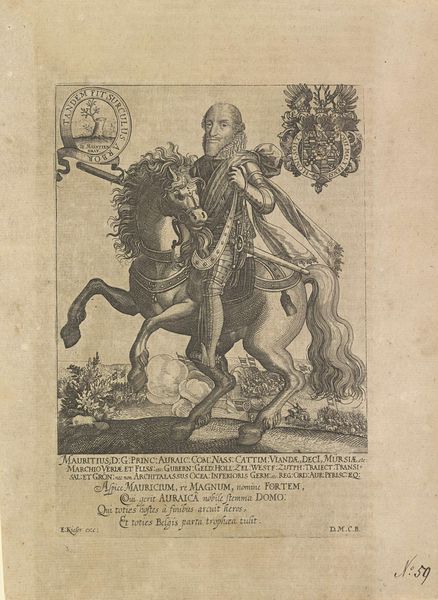

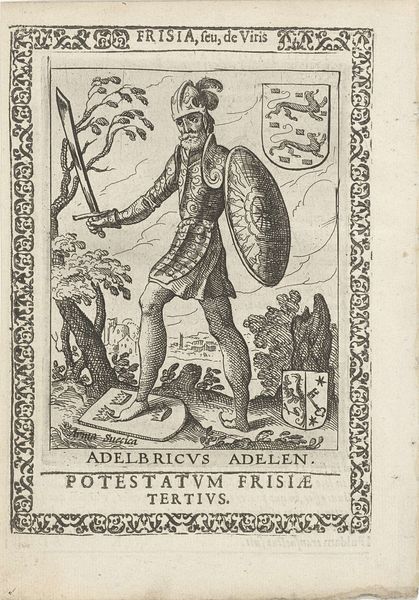

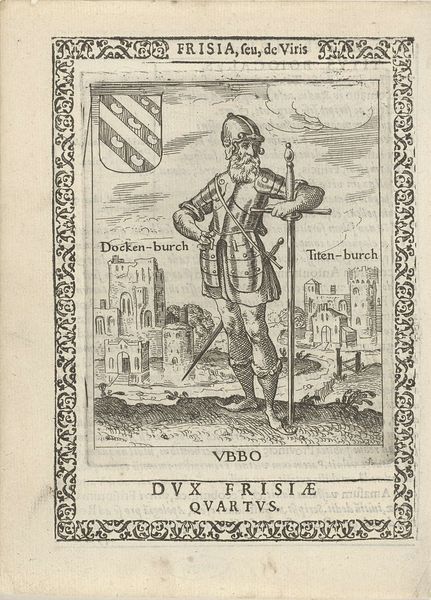

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 125 mm, width 100 mm, height 158 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a striking print titled "Ulrich I, eerste graaf van Oost-Friesland" dating from 1618 to 1620. The artist is Pieter Feddes van Harlingen, and it's an engraving. Editor: The linear quality gives it a sense of formality, but something about his stance seems almost theatrical. Curator: The work depicts Ulrich I, the first Count of East Frisia. Think about the sociopolitical conditions that allowed him access to power, it’s wrapped up in reformation history and struggles against larger empires. Editor: Let's examine the texture—look at how the artist uses engraving techniques to simulate the gleam of the armor, and how he indicates material through controlled, expressive lines. The frame, too, is very involved. What type of process do you imagine was used to make the frame versus the portrait? Curator: Indeed. I am drawn to the framing narrative and Ulrich’s specific positionality as the "first," a very delicate place in systems that aim to naturalize social structures. This imagery reinforces those values, no? How does the chosen setting serve to reinforce patriarchal rule and aristocratic heritage, and what impact might the emphasis on primogeniture have had on other members of the Count's family or other marginalized folks under his power? Editor: The symbolic richness is something else. He carries a sword, the destroyed architecture looms nearby, but is dwarfed. The landscape on the right adds a dynamic counterpoint to all the armor and fortification—and then the lines... so, lines evoke texture and volume in an extremely efficient way. But why a print instead of an oil painting or a casting in bronze? Curator: That consideration helps us interrogate the role of printmaking in disseminating images of power. And the act of collecting… This image helps tell the story of European social consolidation, and how these narratives intersect with gender, violence, class, ability. The very circulation of this print makes it part of a matrix of oppressive structures that impact real bodies. Editor: Considering the amount of production these processes might demand and require leads me to think that it represents something else: status, or possibly access. Curator: That's fascinating. I never looked at it this way before. Editor: Agreed; I see your points as well, and hadn’t quite noticed how gender, historical factors, and other considerations could further nuance our view. Curator: Thinking through Ulrich I within the wider sociopolitical framework certainly reframes his position beyond a simple representation of authority.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.