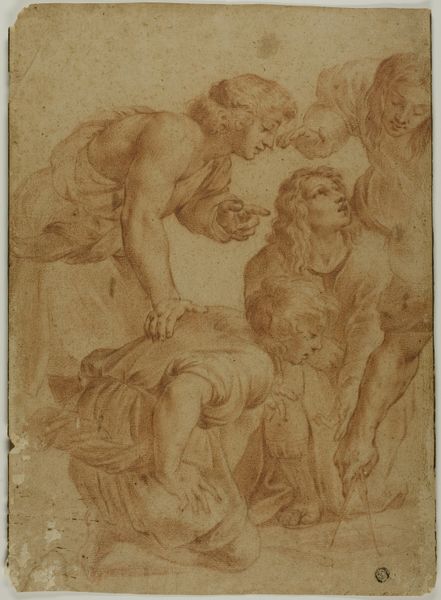

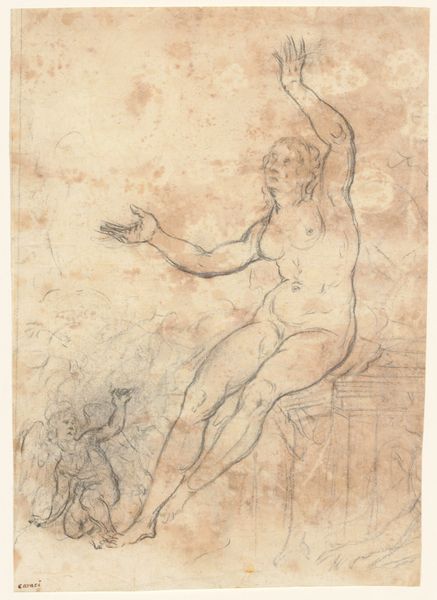

Studies for Four Figures (recto); Composition Sketches for Groupings of Figures on Clouds (verso) 1600 - 1614

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, charcoal

#

drawing

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

charcoal

#

nude

Dimensions: 16 x 10-5/16 in. (40.6 x 26.1 cm) maximum; irregular borders

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this drawing is called "Studies for Four Figures" by Jacopo Palma the Younger, from around 1600 to 1614. It’s done with charcoal and white chalk. I’m immediately struck by the tension in their bodies. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, this drawing, situated in the Mannerist style, reveals a lot about the social and intellectual anxieties of its time. Palma the Younger, working in Venice, was deeply impacted by the Counter-Reformation. What seems like just a study of figures becomes much more. Look at the exaggerated musculature and the strained poses; doesn’t that remind you of the anxieties and struggles of the period? Editor: I can see that. It's like the bodies are containers for larger societal pressures. Are the figures intended to represent a particular story or subject matter, then? Curator: It’s open to interpretation. What narratives do *you* think they evoke? Do you see the nude form, often a symbol of power and classical ideals, being challenged or perhaps weaponized here? Remember, artistic patronage during this era often came with strings attached, reflecting specific ideological agendas. These bodies aren't simply aesthetic exercises; they are loaded with meaning. Editor: So, by playing with those traditional forms, Palma the Younger is engaging with those larger sociopolitical forces? Curator: Precisely! And by choosing charcoal – a medium linked to draftsmanship and preparation – he invites us to see art as a process, not just a finished product, reflective of social movements in progress. Editor: I see it now! I never would have considered the historical implications just from looking at the figures alone. Thanks, that really opens up the conversation! Curator: Indeed. Looking beyond the aesthetic allows us to understand the powerful dialogues art has with culture and history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.