#

pencil drawn

#

wedding photograph

#

photo restoration

#

charcoal drawing

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

framed image

#

limited contrast and shading

#

19th century

#

portrait drawing

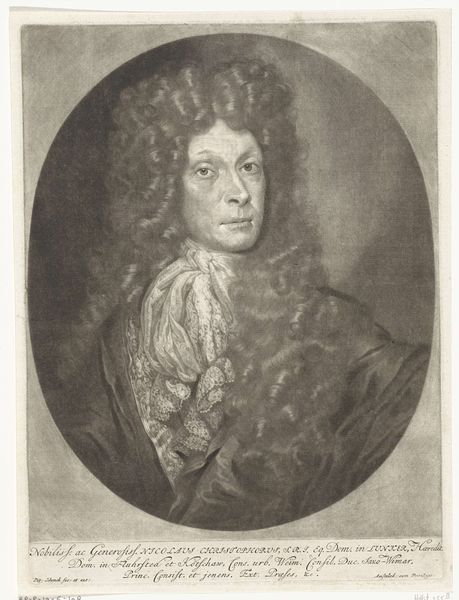

Dimensions: height 330 mm, width 247 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a portrait of Hendrik Casimir II, Count of Nassau-Dietz, likely created between 1675 and 1699. What's your first take? Editor: It strikes me as quite severe. The stark monochrome, the figure encased in armour – it evokes a sense of rigid formality and power, of course. It makes you wonder about the labor it took to craft that armor! Curator: Absolutely. The etching itself is fascinating when considered against the socio-political backdrop of the Dutch Golden Age. We're seeing the assertion of identity and authority. The sitter's class position reflected through the means available for such portrayals, and to maintain power via portraiture. Editor: Agreed. Consider the materials involved—the paper, the ink, the etching process. Each speaks to a level of artisanal skill but also to the Count’s investment in projecting this image. The production itself relies on the labor of others. Curator: Precisely. This wasn’t a quick snapshot, but a carefully constructed representation intended to communicate specific messages about his role, and legitimacy. We need to understand it against contemporary political and social dynamics, with class playing an outsized role for centuries in Europe. Editor: Right, the very choice to be immortalized in armour says so much about performative masculinity of the time, the intersection between power and material presentation is stark, even today. And how it's been mediated, reproduced, distributed as prints. What survives becomes the story. Curator: Indeed. The image would be circulated, reinforcing his power, perhaps quelling discontent or solidifying alliances. His likeness being presented so formally suggests his social position and personal self are completely intertwined. It's the gender and role rendered in a tangible item. Editor: Well, it definitely highlights how the creation and dissemination of art serves very specific social functions tied directly to power structures. It makes me reflect on how those systems of support and labor persist into our contemporary art world. Curator: Precisely, studying a portrait such as this can reveal just as much about its subject, if not more, regarding society as a whole, and the construction of these roles of power. Editor: Agreed, viewing art, whether we intend to or not, demands interrogation regarding social relationships as represented in objects and how deeply they structure our view.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.