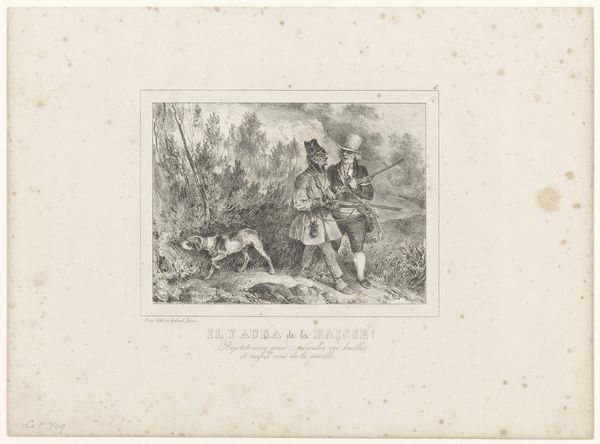

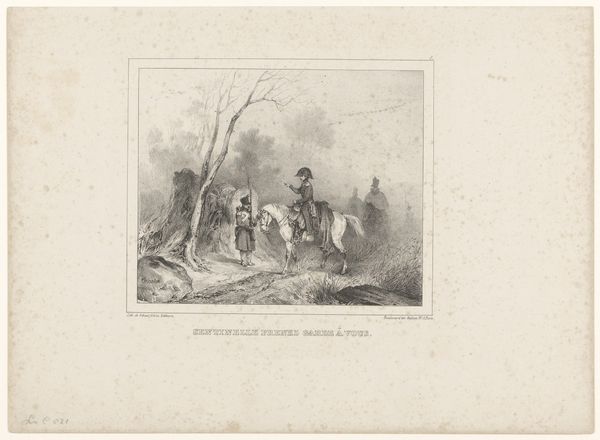

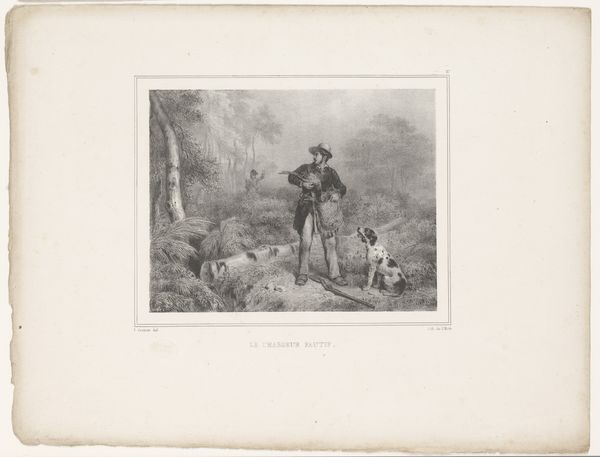

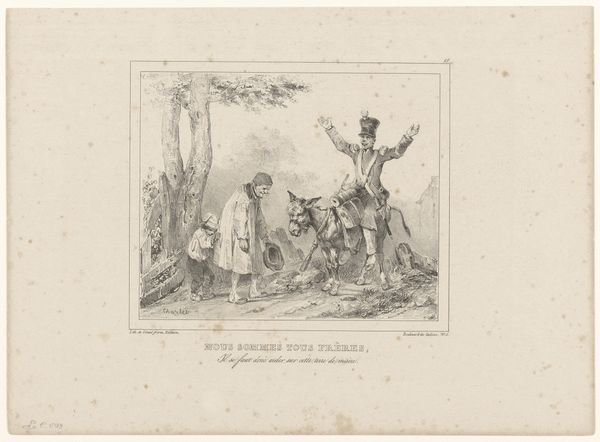

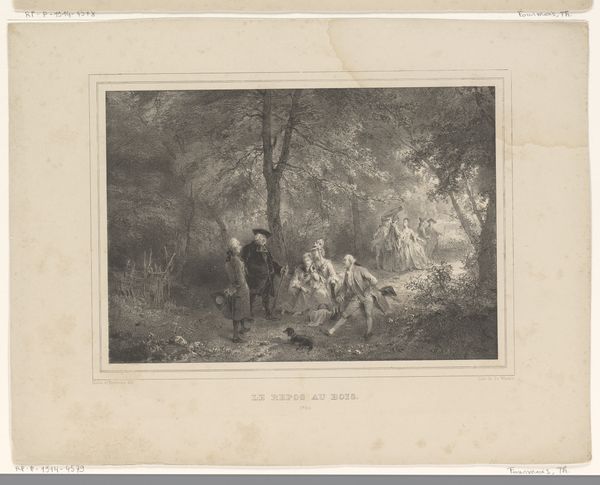

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

forest

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 445 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Hendrik Wilhelmus Last’s "Children and a Wolf in the Woods," likely created sometime between 1827 and 1873. It's an engraving on paper, and my first thought is how it seems to depict a really dramatic encounter, but I'm unsure what it reflects about people, history or its culture. What do you see in this piece, especially considering when it was made? Curator: What I find striking is the raw vulnerability depicted. It invites us to think about the romanticized notions of nature that were so popular at the time, and how those notions often masked very real dangers and anxieties, especially concerning children. Notice the children's clothing. How does that influence our understanding? Editor: Well, their clothing seems pretty standard for the time, like work clothes. Does it relate to class? Curator: Exactly. Consider the rise of industrialization and the shift of families from rural areas to urban centers. This image presents us with a "natural" setting, but for whom was that nature accessible or dangerous? For poorer families, the woods were not necessarily a picturesque escape but a place of labor and very real threats. The wolf embodies those threats. The children's relative social position makes the whole image a lot less romantic. It underscores power imbalances in society. Editor: So, the artist might be challenging that idealized view of nature? Curator: Precisely. It prompts us to question whose experiences are privileged in the dominant narratives about nature. It's an invitation to think about class, labor, and childhood, not as sentimental concepts, but as lived realities shaped by broader socio-economic forces. What did the word 'nature' even mean for children back then? Was the encounter represented a constant fact? Editor: I hadn't thought about it that way. It makes me wonder about how we romanticize certain periods and landscapes, forgetting the hardships faced by many. Curator: And it pushes us to critically examine how those romanticized views are constructed and maintained, often obscuring the experiences of marginalized communities. Thank you, your thoughts bring nuance to my work. Editor: This was great; thank you for your time!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.