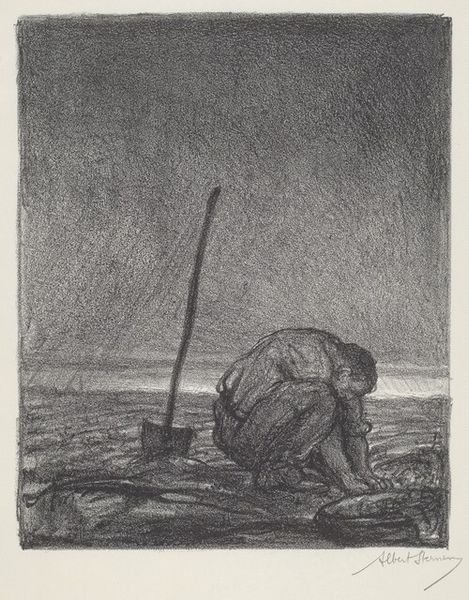

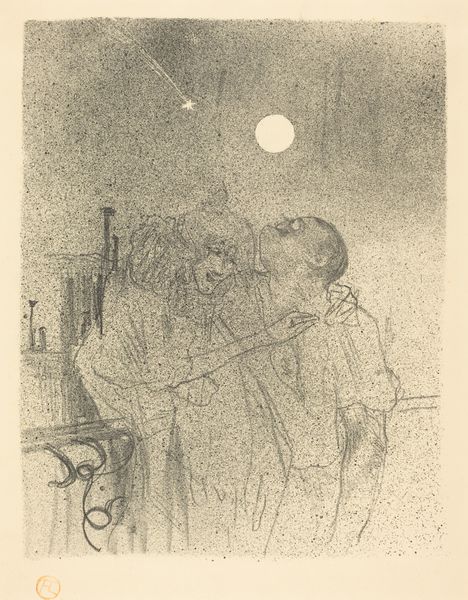

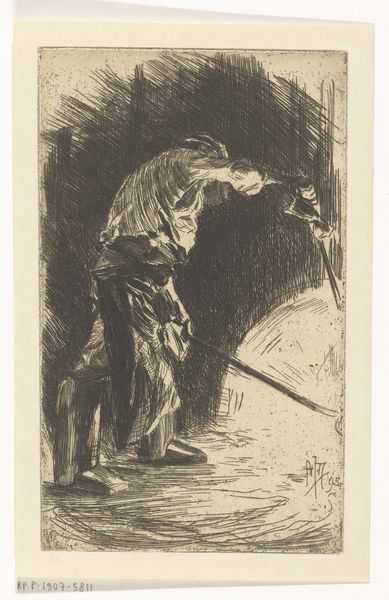

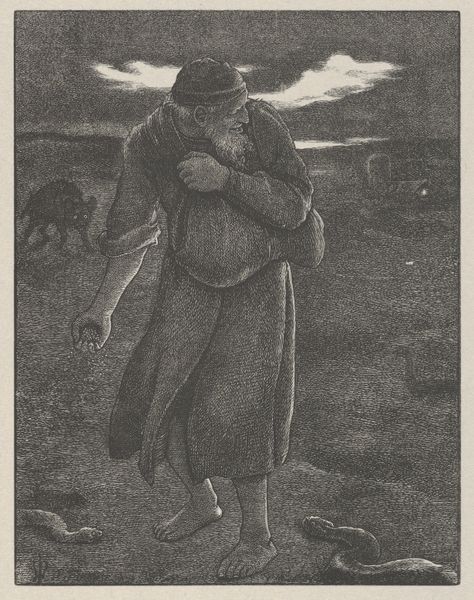

Dimensions: Image: 220 x 177 mm Sheet: 282 x 214 mm

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: "The Scavenger," a 1939 piece realized in pencil, print, and charcoal by Mildred Bernice Nungester, confronts us. What sensations does it initially conjure for you? Editor: The scavenging cat in the bottom corner seems to dance in contrast with the quiet solemnity that seems to emanate from this barrel rifler. It reminds me of grainy, old movies—a slice of hardscrabble life bathed in a surreal glow. Is it moonlight, or something else casting such a dramatic shadow? Curator: The composition employs high contrast, a stark juxtaposition of light and shadow. Note the centralized moon or perhaps it's sun, dominating the upper quadrant which opposes and sets the stage to a near uniform and complex darknesses that make up both ground and subject in the lower quadrant of the print. The tonality serves not just to illuminate, but to isolate and focus our gaze upon the activity of "scavenging." Editor: I wonder what he’s looking for? Is he hungry, or just curious? There's something almost mythic about him silhouetted there – this ordinary act is now imbued with a heavier emotional load. He’s a searcher, one of us. Is Nungester imbuing some special reverence to his act of labor and maybe her own? Curator: Labor it is, however the aesthetic execution complicates any didactic simplicity of representation or social message, doesn’t it? The textural rendering – that hatching, the chiaroscuro effects—all contribute to an undeniable pictorial richness that transcends pure representation. She isn't just showing us a man scavenging. She's engaging with form. Editor: Perhaps it’s precisely because the technical aspects and rich detail of form heighten our empathy. The rough texture emphasizes the reality of the figure. Maybe that is her point? That there is inherent dignity, even beauty, in that starker existence? She invites us to pause, and truly *see*. Curator: Precisely, a moment of “seeing” that's been shaped by artistic decisions related to texture, contrast and even composition, each strategically positioned to trigger particular sensations and contemplation regarding subject in frame, to elicit just such reflections that may expand what could be deemed beautiful or what could be called ugly. Editor: So, it’s the visual language – line, shadow, composition – that amplifies our feelings, rather than dictating them? Through the use of pencil and print, Nungester doesn't simply present reality; she reshapes it and invites us to delve into the hidden corners. That’s the thing about seeing, isn't it? It never stops at the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.