![Untitled [portrait of a young girl seated in the 'Gurney chair'] by Jeremiah Gurney](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzI0OWZhNmU5LWVmZjctNDBlYi1iYWQwLTM0ZjUwNTMxMjM4ZS8yNDlmYTZlOS1lZmY3LTQwZWItYmFkMC0zNGY1MDUzMTIzOGVfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

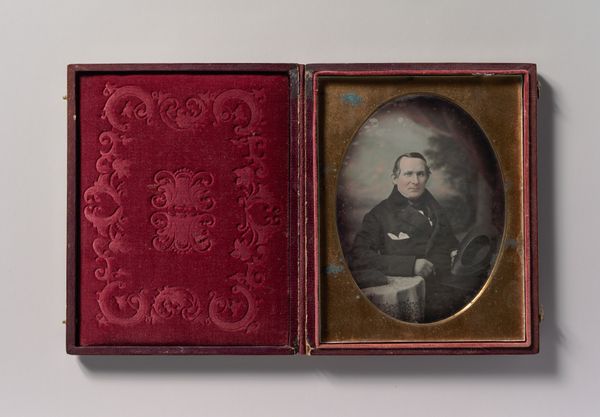

Untitled [portrait of a young girl seated in the 'Gurney chair'] 1852 - 1858

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: 3 1/4 x 2 3/4 in. (8.26 x 6.99 cm) (image)3 5/8 x 3 1/8 x 3/4 in. (9.21 x 7.94 x 1.91 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "Untitled [portrait of a young girl seated in the 'Gurney chair']" created by Jeremiah Gurney between 1852 and 1858. It’s a daguerreotype, housed at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What immediately strikes me is the incredible preservation of this fragile medium, and the way the dark palette contrasts with the elaborate presentation case. What stands out to you? Curator: For me, it's the context of production. This daguerreotype isn't just a portrait; it's a commodity produced within a burgeoning industry. Think about the materials involved: silver-plated copper, mercury vapors, and the specialized knowledge required to manipulate them. The “Gurney chair” itself becomes a prop, a repeatable element of his studio's brand, a mark of aspirational consumerism in that era. Editor: That's fascinating! I hadn't considered the industrial aspect of it. It felt very personal and intimate, but it's a commercial product, in a way. How would you say this challenges the notion of 'high art?' Curator: Exactly! Daguerreotypes, like this one, blurred the lines between art, craft, and industry. It was more about access. Photography democratized portraiture; it was quicker and more affordable. So the question is not is it Art? but what materials and labour are deployed, how are these made accessible, and for whom? How does the case itself, with its plush velvet and gilt detailing, play into the act of marketing this new technology and service? Editor: That makes perfect sense. The elaborate case and even the sitter’s attire point towards a burgeoning middle class able to afford such luxury and participate in visual culture. Curator: Precisely. Looking at this portrait through the lens of its material production allows us to see the social and economic forces shaping photographic practices in the 19th century. It goes beyond mere aesthetic appreciation. Editor: I see the image so differently now, thinking about the means of its production and its social reach. Thanks for highlighting the industrial process, this context gave new perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.