photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

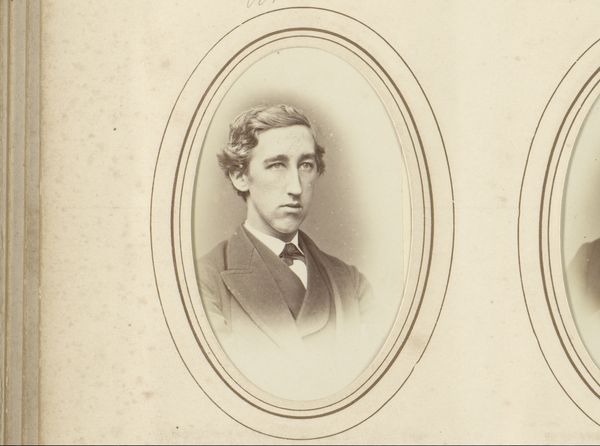

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a gelatin-silver print, "Portret van een man" by Eduard François Georges, dating from around 1860 to 1885. It has a melancholy feeling, stark and minimal in composition. What strikes you about this work? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider how portraiture during this period served as a tool for constructing and reinforcing social identities. Consider how access to photography, even in its early forms, would have been dictated by class and social standing. Who was represented, and how were they represented? Editor: It seems like he is from an upper class. Is that communicated intentionally through the image? Curator: Absolutely. His attire—the suit, the bow tie—signals a certain level of affluence and adherence to societal norms. But I'm interested in what isn't overtly stated. What can we infer about his role in society, or the expectations placed upon him? Is there something being performed here? Think about the very act of commissioning a portrait, especially then, it’s a statement. A bid for posterity and acknowledgement of status. What’s also key is what does realism mean at the time of early photography? Editor: That’s something I hadn’t thought of. Curator: Also consider how realism functioned differently depending on gender and race. White men often had the privilege of being represented as individuals, while the representation of others was often dictated by stereotypes or colonial narratives. How does this image uphold or challenge those dynamics? Editor: So the man's identity isn’t just individual, but tied to broader societal structures? Curator: Precisely. By looking beyond the surface, we can start to unpack the complex power dynamics embedded within seemingly simple portraits like this one. And understand more deeply not just who is represented, but what those representations meant at the time and mean today. Editor: That really reframes how I see this portrait, making it much more than just a historical image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.