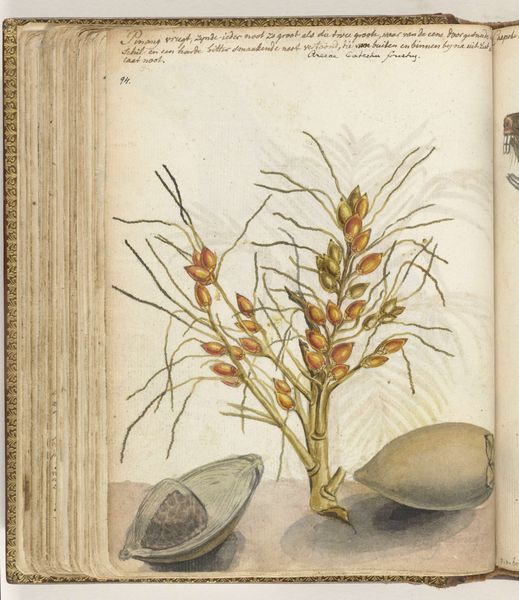

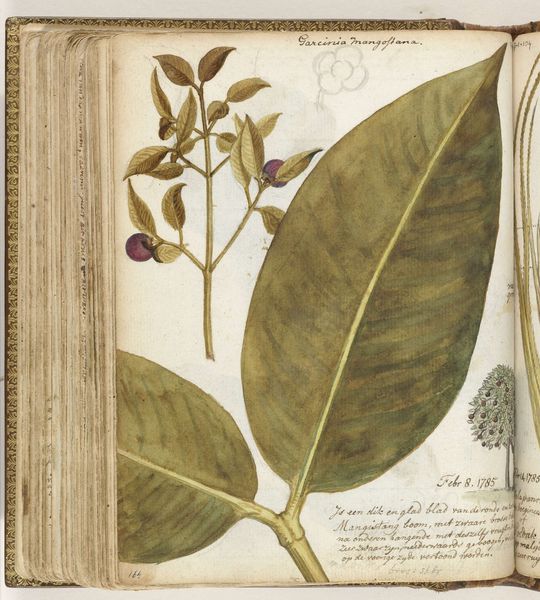

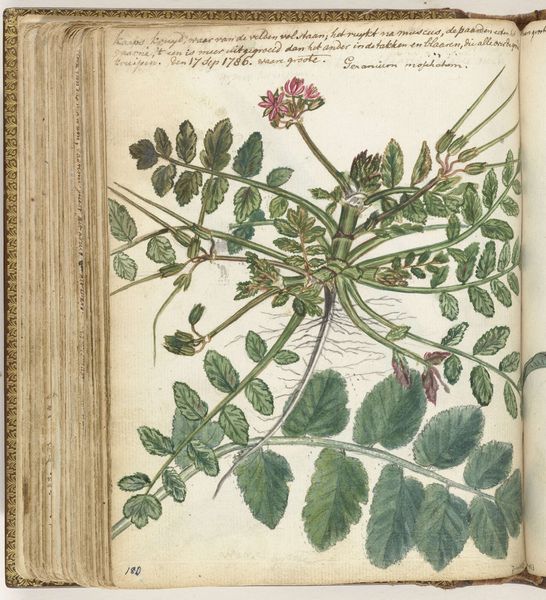

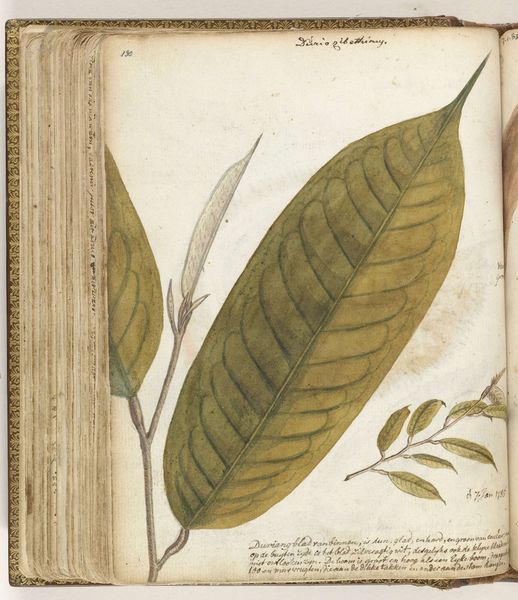

drawing, coloured-pencil, paper, watercolor

#

drawing

#

coloured-pencil

#

landscape

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes you first about this drawing titled “Mieren en rijst,” potentially made between 1779 and 1789 by Jan Brandes? It seems to be a watercolor and coloured-pencil piece on paper, detailing rice and… ants. Editor: Oh, it has such an intriguing fragility. The pale yellows and blues, the aged paper... it's like looking at a whisper of the past, a captured breath from a humid field somewhere far away. And yes, the juxtaposition of rice and those little scurrying ants… There’s something symbolic about that, don’t you think? Curator: Absolutely. I think it’s crucial to consider Brandes’ role as an observer in this period. His drawings weren’t just aesthetic; they were part of a larger colonial project of cataloging and understanding resources. Think about how the drawing would be received – a record of a plant crucial for both survival and economic value. The medium itself, watercolor on paper, was relatively cheap to produce and therefore effective for data recording in the field, or preparatory drawings later reproduced as a woodcut. Editor: Data recording, yes, but there’s an artistry here too, however utilitarian it may have been. That delicate rendering of each grain of rice! It transcends pure utility. One can almost feel the artist's hand, the focused gaze transforming observation into reverence, of sort. Perhaps even Brandes' relationship to the process is more collaborative and entangled than authoritative? And look closely at those annotations in the margin – those careful notes seem to almost embrace the artistic depiction of his chosen specimen. Curator: True, the act of drawing is itself a form of engagement, even an implicit expression. The annotations contribute to a specific discourse regarding colonial resources in that moment, I feel that those can give us key details related to material processing and local naming convention. But in a colonial context, labor and access are often absent from the work itself. Editor: That is so very important to keep in mind when approaching this seemingly simple yet profoundly complicated historical document. The act of capturing nature on paper like this freezes the land in time. It does hold incredible amounts of precious information and speaks of its time and, perhaps unwittingly, something deeper as well, the natural wonder found in a grain of rice. Curator: I agree. The material context combined with your intuition has enriched my appreciation for this delicate yet robust work. Editor: And the methodical structure that frames your insightful consideration helps to enrich my feeling. A rewarding conversation that I'll carry with me now while seeing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.