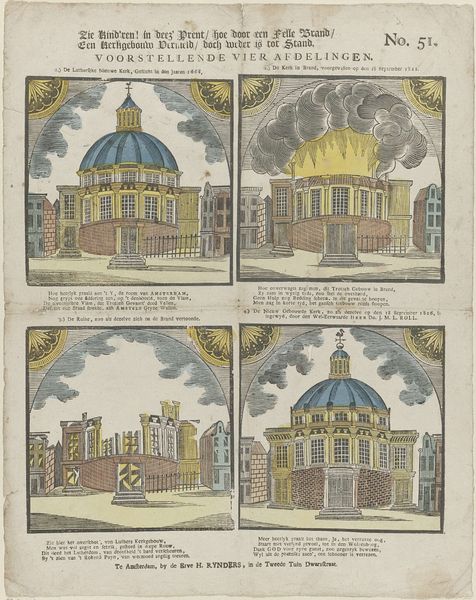

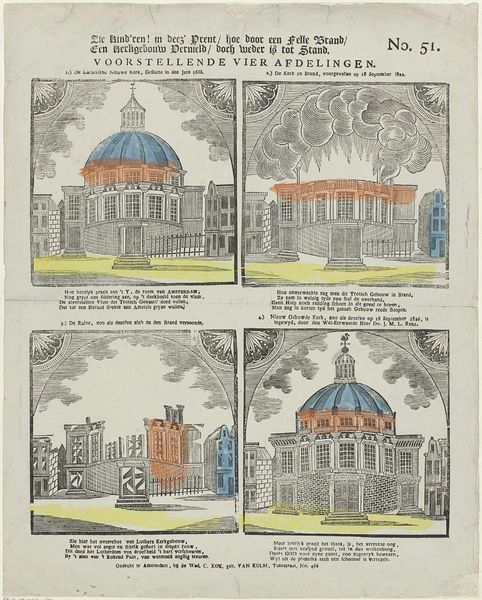

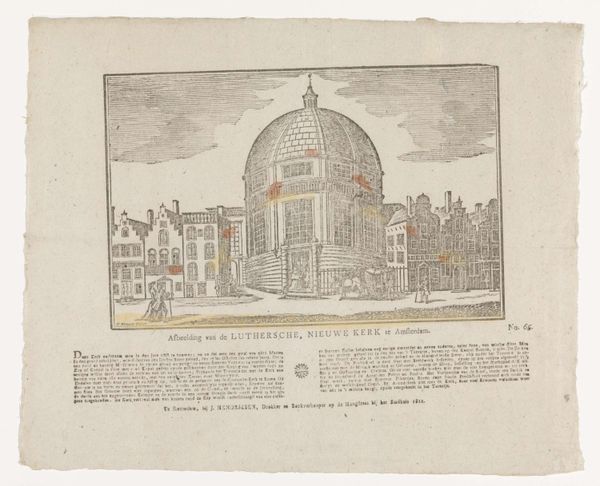

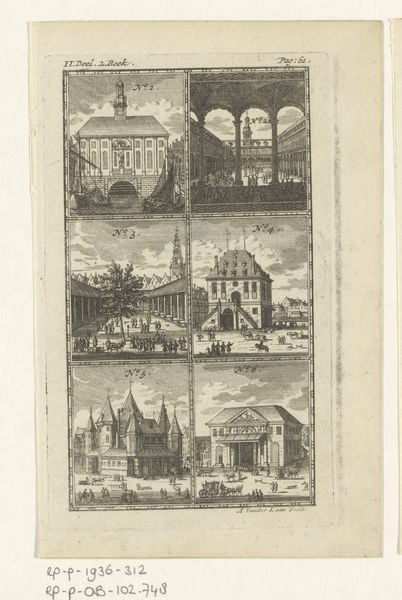

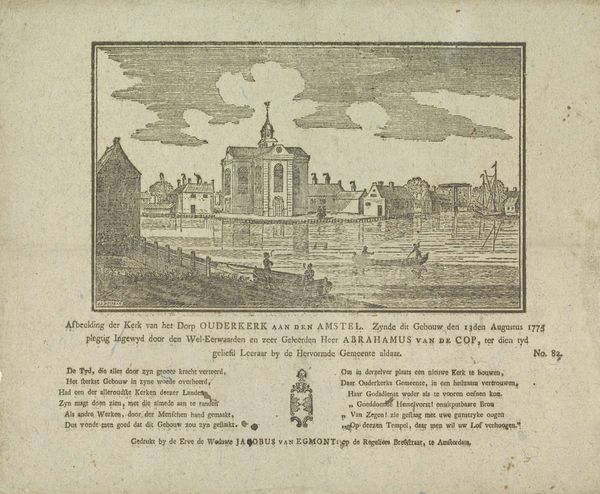

Zie kind'ren! in deez' prent / hoe door een felle brand / Een kerkgebouw vernield / doch weder is tot stand. / Voorstellende vier afdelingen 1842 - 1866

0:00

0:00

weduweckokvankolm

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving, architecture

#

aged paper

# print

#

old engraving style

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

pen and pencil

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 416 mm, width 337 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This print, "Zie kind'ren! in deez' prent…," which translates roughly to "See children! In this print…," was created by weduwe C. Kok-van Kolm sometime between 1842 and 1866. It's an engraving depicting four stages of a church's destruction and reconstruction. The artwork, held at the Rijksmuseum, gives me the impression of a graphic novel—each panel unfolds like a comic strip page documenting events with the pen-and-ink cross hatching, which gives it that sort of crude newspaper feel of that time. What strikes you immediately? Editor: The narrative, presented in four frames, begs us to consider not only the church itself but also the values embedded in its destruction and rebuilding. This speaks directly to resilience in community following trauma. The fire, undoubtedly a major social event for this town and people, now reconstructed anew from literal ashes speaks to faith itself, of how the materials were procured, paid for. Curator: Right, the means of production become central to the story it tells. Each stage is visually distinct, meticulously rendered with a focus on architectural detail. Look at the crispness of the lines used to define the facade in each frame versus how smoke plumes into frame, and consider how it's communicating to us that it's architecture—buildings erected through labour. You sense the hands involved. I'm curious about what audience was thought of when it was made. What social classes are thought to appreciate it most, and how was this type of work regarded alongside ‘high art’? Editor: It also makes me think about how collective identity is forged through shared experience and, critically, shared recovery. The visual story implies a narrative of resilience after collective shock that asks who participates in community now renewed. This goes beyond architecture to suggest renewal and regeneration of social bonds. Did it explicitly appeal to certain ethnic or cultural backgrounds or ideologies that perhaps were regarded as subversive by others? Curator: The social context and materiality intertwine powerfully here. Given the likely cost of the engravings at the time of printing, distribution and audience are key material factors to reflect upon today, along with the labour necessary to make these engravings from the master drawings in the first place. We should try and investigate them further perhaps and also see who actually purchased her printed work when she was alive? Editor: Agreed. Thinking more on the intersection of materiality and social message lets me revisit the message itself of building back up from fire. If one asks "Who builds?" and "Who benefits?", the dialogue becomes deeper. Curator: Absolutely, by attending to labor and material reality, this work offers such richer layers to explore and research more deeply. Editor: Exactly. The art deepens itself in the process of reflection upon process!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.