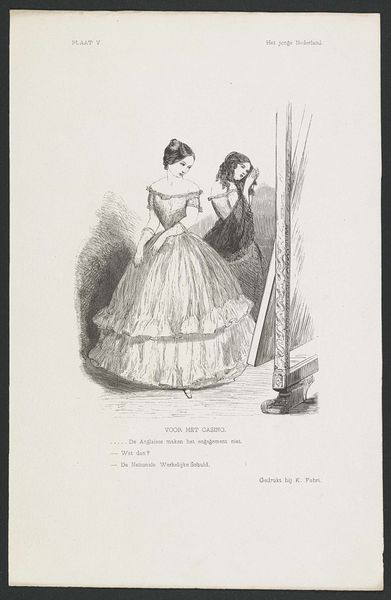

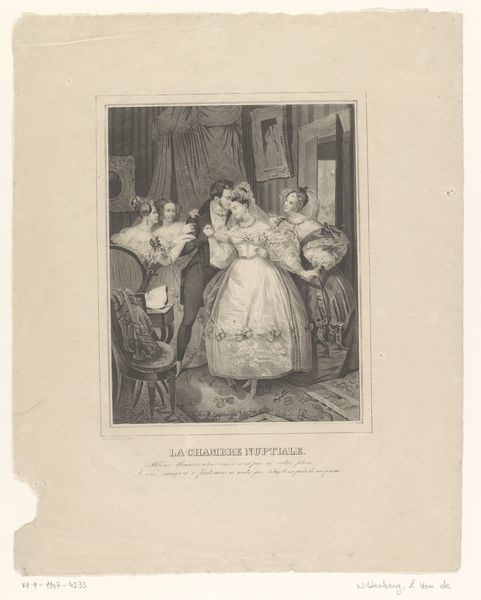

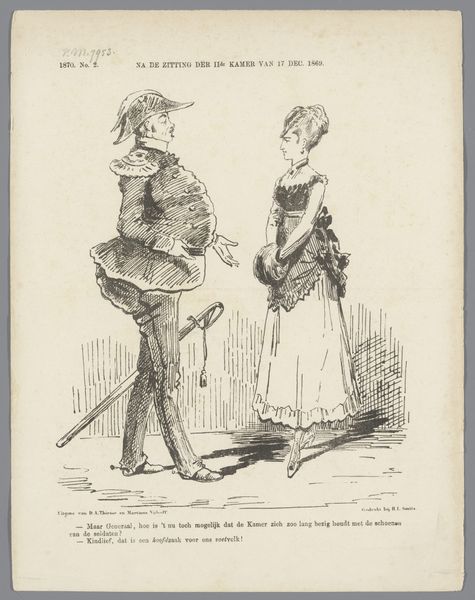

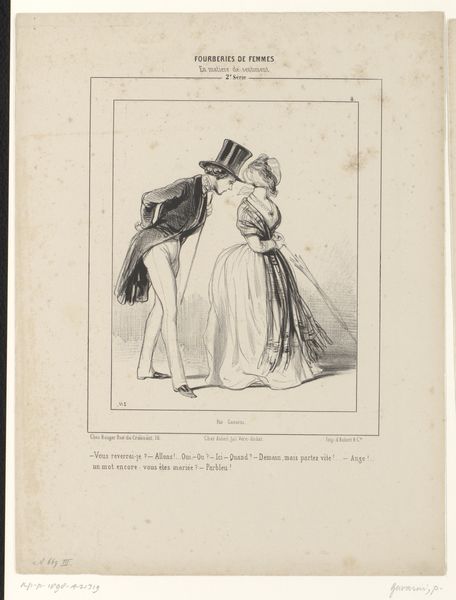

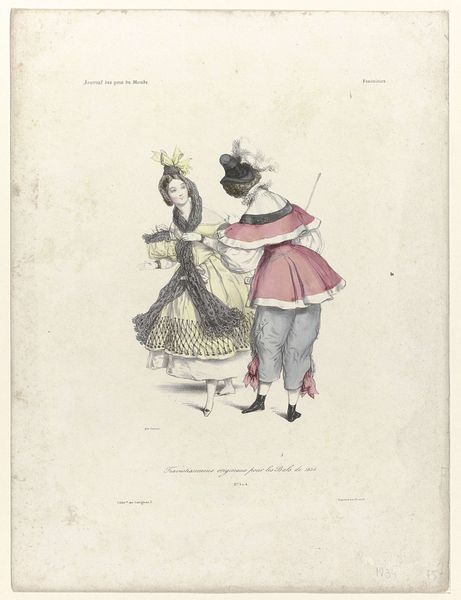

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pencil sketch

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 278 mm, width 185 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, "Two Children in Fine Clothing" from 1847, seems a poignant display of Romantic-era Dutch aesthetics, no? Editor: Yes, created by Rombertus Julianus van Arum, and held in the Rijksmuseum. The children look like dolls with those massive eyes. I find the work charming but stiff. How do you read the social and material context within this piece? Curator: The clothing tells a complex story of textile production, of labor. Consider the detail captured in the engraving—each fold of the girl's dress, the boy's elaborate collar. This speaks to both the engraver’s skill and the source materials. What kind of labor produced their clothes? Who consumed images like this, and how does it mirror power dynamics within Dutch society at the time? Editor: Right, the means of production. Engravings were, relatively, more accessible than paintings for distribution. So, could this be considered a way of marketing a certain type of... Dutch ideal? Curator: Precisely! This "Dutch ideal" is deeply intertwined with notions of status and capital. Who can afford such elaborate clothes, and who profits from their making and circulation? Even the 'genre-painting' aspect tells a story: it pretends to simply reflect real life, but is very purposefully manufactured for consumption. The question then is, how does the materiality of the print, its capacity for replication and distribution, affect our understanding of these social relationships? Editor: It makes the image almost like a commodity in itself! So by considering how it was made, we are prompted to explore social stratification from a new angle. Curator: Exactly. Thinking materially allows us to scrutinize the supposed neutrality of images and unveils embedded power structures. It challenges our understanding of the image's production, distribution, and consumption during its historical context. Editor: That makes a lot of sense. Thanks for illuminating those details!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.