drawing, print, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

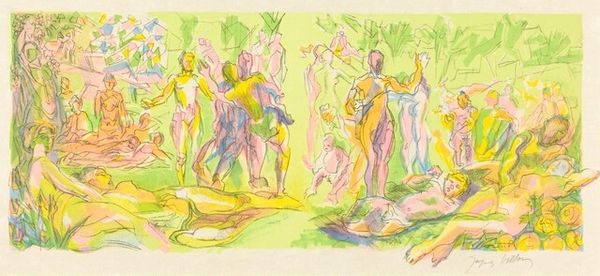

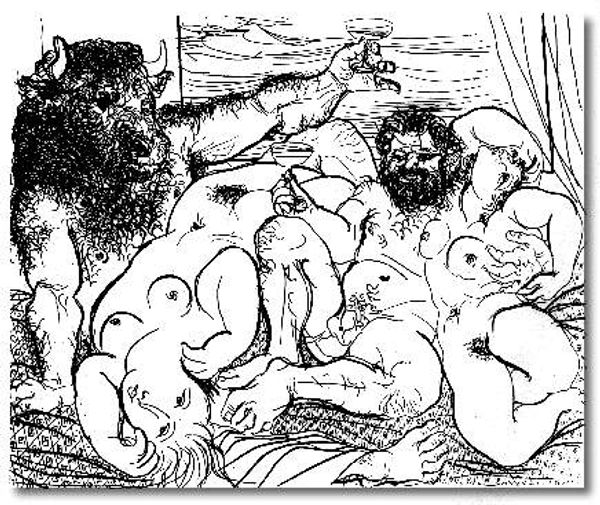

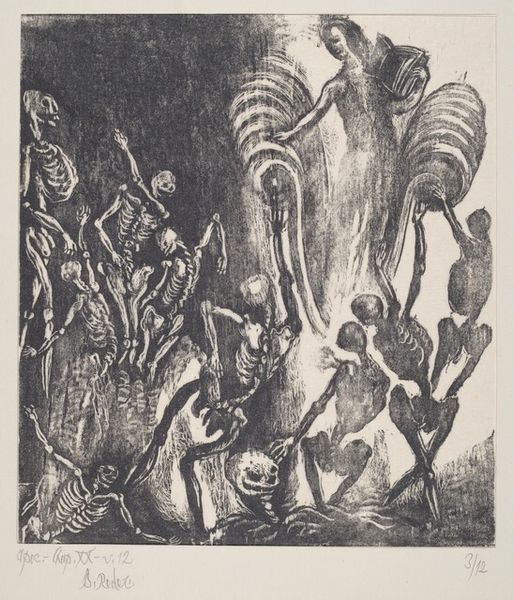

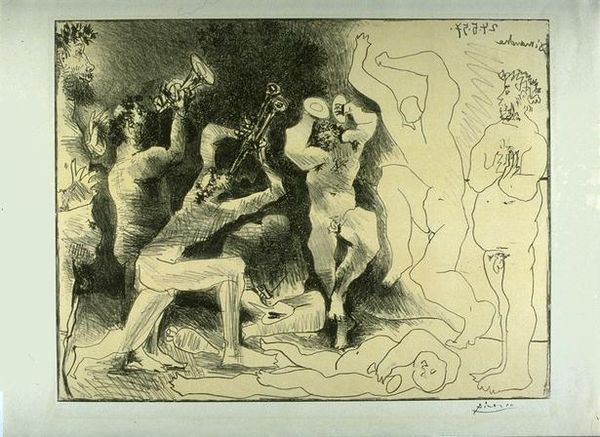

Curator: We're standing before Jacques Villon's "Fourth Bucolic: The Golden Age," created in 1955. It's an ink drawing and print. Editor: My first impression is one of dynamic chaos. There's an immediate tension between the figures’ implied movement and the overall sense of idyllic repose. What are we meant to feel? Curator: The interplay of those elements, as you astutely note, is key. Villon constructs this scene using a network of lines and planes; look at how the figures are fragmented, almost cubist in their rendering. The ink lends itself to capturing form and volume with relatively little variation in mark-making technique. Editor: I'm curious about the implied labor behind it though—the act of making these multiples, this dissemination of an elite art form like painting or drawing in order to allow many people access. Here, Villon's turned printmaking, a supposedly "lesser" craft, into something visually remarkable. Curator: Consider the bucolic tradition. Villon reframes it through a decidedly modern lens, doesn't he? The pastoral scene, the 'Golden Age' evokes longing. But this age isn't smooth—the fractured forms don't allow the eye to rest. They represent something unsettled in the concept itself. Editor: This fragmented nature resonates with modern alienation from nature too, in contrast to traditional pastoral scenes, that romanticized nature and working class relationships, what is it telling us about labor then, is this artwork saying that even leisure cannot exist outside of work? Is rest even achievable in modern capitalism, maybe that is why people appear in such a state of confusion here. Curator: It becomes a poignant question: can we ever truly return to that untainted, pre-industrialized harmony? This print almost insists on the impossibility, as it wrestles the idealized pastoral into a contemporary form, acknowledging the artifice. Editor: Perhaps, though I cannot help feeling that Villon's hand – visible in every carefully etched line – points to how artists reshape labor practices. The artwork remains valuable, though not just through commerce but also by documenting processes, actions, or histories of making—challenging notions of originality, value, or function. Curator: Looking closely at "Fourth Bucolic" reveals the many layered meanings Villon manages to convey, creating a work that challenges assumptions. Editor: Yes, and one that underscores art as an outcome, a record of labor’s transformative force and its engagement within the contemporary social conditions of his time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.